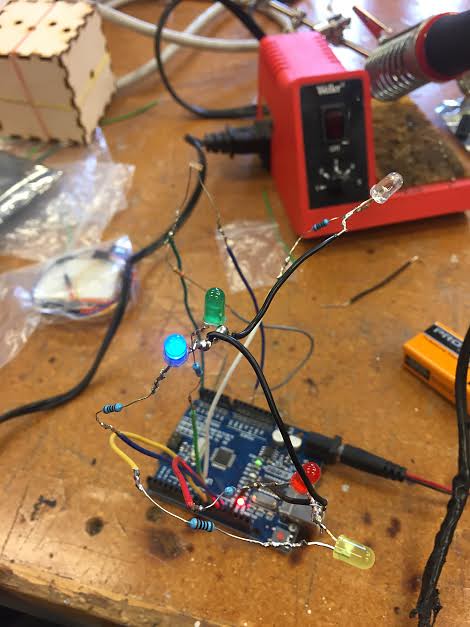

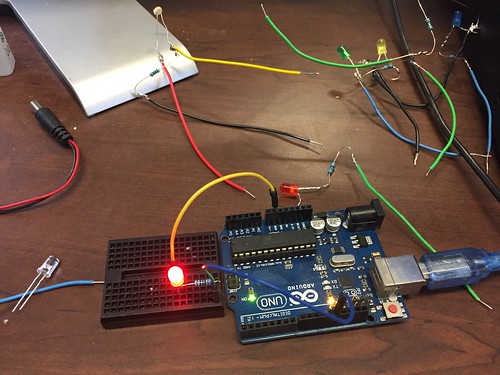

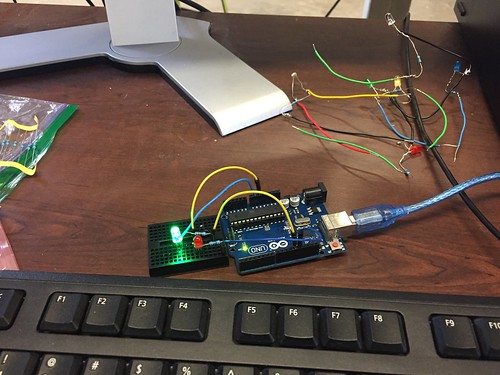

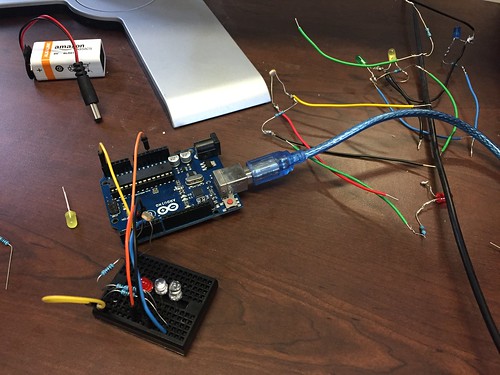

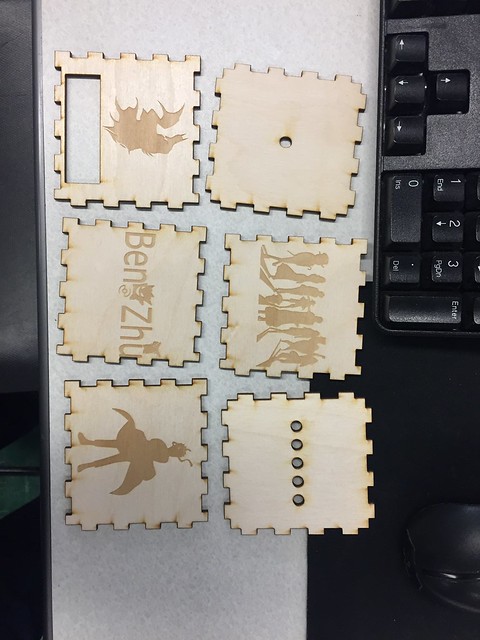

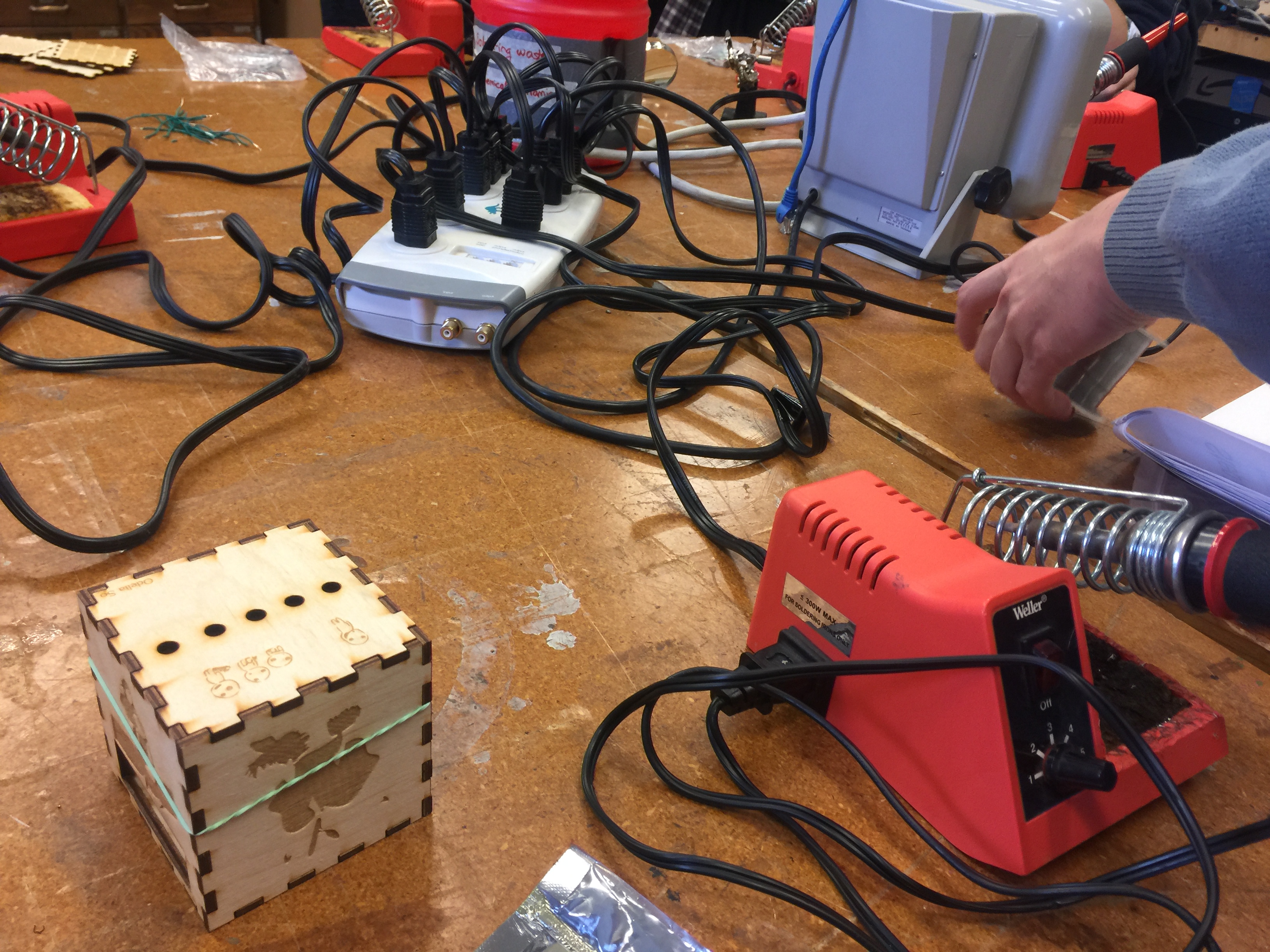

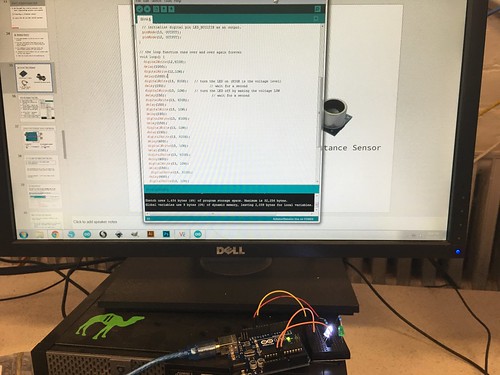

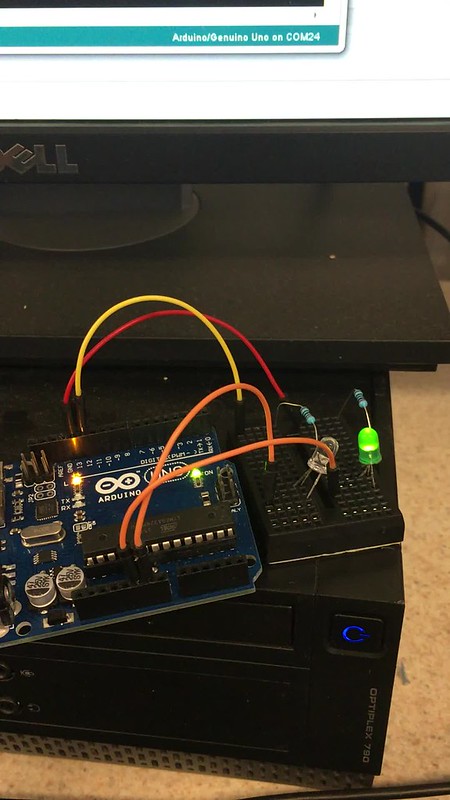

This week marked our last class at the Champaign Community Fab Lab, an innovative and dynamic maker space located on the campus of the University of Illinois. While in previous classes we have worked with soldering joints, encoding Arduino Uno circuit boards using Arduino’s open-sourced software, and wiring resistors and LED lights into breadboards, this week was the culmination of all our of efforts. We were able to finally assemble the photo resistor in its entirety. While in the past two weeks we took care of the actual photo resistor and its assembly, we still needed to create a structure that would house the part. In order to do this, Clinton and Julia, our two exponentially patient teachers, instructed us on the basics of Inkscape (a graphics editor similar to Adobe Photoshop), and on using the two laser cutters housed at the Fab Lab. The objective of utilizing these tools was to assemble a wooden, six-piece cube that would house the photo dependent LED light resistor. As mentioned, the software used to create the designs on the sides of the cubes was Inkscape, a completely free, open-source platform that appears to be user-friendly yet still able to make complex designs. Once the template for the wooden cube was downloaded, some manipulation was required in order to guarantee the fitting of the wood. In order for the laser to properly cut the wood, certain formatting and thickness adjustments had to be made. Using Inkscape, we traced black and white images taken from online, and, once finished, the PDF file was loaded onto the laser cutter. The laser etched the designs into the wood which created the downloaded images in a process called raster scanning, while also making the actual cuts to create the box (called vector scanning). The cutting process lasted just a few minutes, as subtractive manufacturing such as laser cutting can be considerably faster than additive manufacturing, like 3D printing.

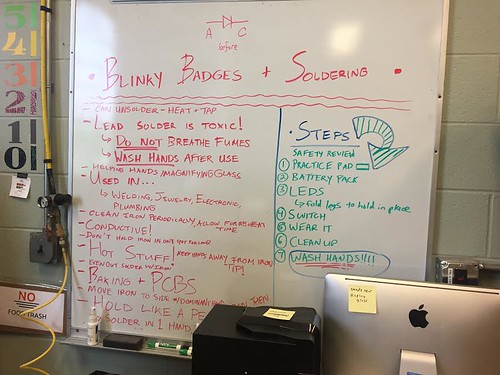

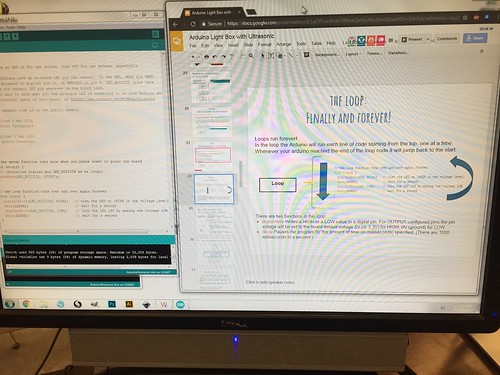

Above is a picture of what the design of my wooden house looked like on Inkscape. While it cannot be discerned through this picture, there are very thin red lines outlining six intricate boxes. The red lines indicated to the laser cutter what needed to be vector scanned, while the black indicated a raster scan. Below is an illustration of the actual laser cutting process, during which the box outlines were being cut. The whole process, including both the design creations and actual cutting, lasted less than seven minutes, a stark contrast from the relatively lengthy time required for 3D printing.

These past three weeks have exposed to me all that the making world has to offer. While I originally assumed the making revolution focused squarely on 3D printing and additive manufacturing as a whole, this experience has brought about the realization that it is obviously much, much more than that. Going forward, I am excited to see how groups choose to incorporate what we have learned into their final projects.