Ever wondered what those K-Pop bands are singing about? Or what the actors in your favorite K-dramas are crying about? Well, wonder no more because this post of Glocal Notes is for you! Needless to say, you are not the only one because a study by The Modern Language Association found that university students taking Korean language classes increased by 45 percent between 2009 and 2013, despite the overall decrease in language learning by 7 percent. According to Rosemary Feal, the executive director of the Modern Language Association, this increase could be a result of young people’s interest with Korean media and culture. Before going into learning Korean, let’s find out about Korean language itself.

The Korean alphabet was invented!

The Korean alphabet was invented in 1444 and proclaimed by King Sejong the Great in 1446. The original alphabet is called Hunmin chŏngŭm which means “The correct sounds for the instruction of the people.” As you can see from the name of the alphabet, King Sejong cared about all of his people.

Before the Korean alphabet was invented, Korean people used Chinese characters along with other native writing systems as a means of documentation. As stated in the preface of Hunmin chŏngŭm below, because of inherent differences in Korean and Chinese and due to the fact that memorizing characters takes a lot of time, the majority of the lower classes were illiterate. This was used against them by aristocrats to put themselves in a higher position of power. As expected, the new system of writing faced intense resistance by the elites who perhaps thought it was a threat to their status and to China. However, King Sejong pushed through his opposition and promulgated the alphabet in 1446.

Below is the paraphrased translation of the preface of Hunmin chŏngŭm.

The language of [our] people is different from that of the nation of China and thus cannot be expressed by the written language of Chinese people. Because of this reason, the cries of illiterate peasants are not properly understood by the many [in the position of privilege]. I [feel the plight of the peasants and the difficulties faced by the public servants and] am saddened by the situation.

Therefore, twenty eight [written] characters have been newly created. [My desire is] such that, each [Korean] person may become familiar [with the newly created written language of Korean] and use them daily in an intuitive way.

A page from the Hunmin Jeong-eum Eonhae, a partial translation of Hunminjeongeum, the original promulgation of the Korean alphabet. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hunmin_jeong-eum.jpg

Korean is simple.

The construct of the system is simple. Because King Sejong knew that peasants did not have hours and hours to spend on learning how to write, he invented a system in which “a wise man can acquaint himself with them before the morning is over; a stupid man can learn them in the space of ten days.” The modern-day script has evolved into 24 characters and is called Hangul (한글) in South Korea and Chosŏn’gul (조선글) in North Korea. Due to its simplicity, both Koreas boast exceptionally high literacy rates, more than 99% in South and North Korea.

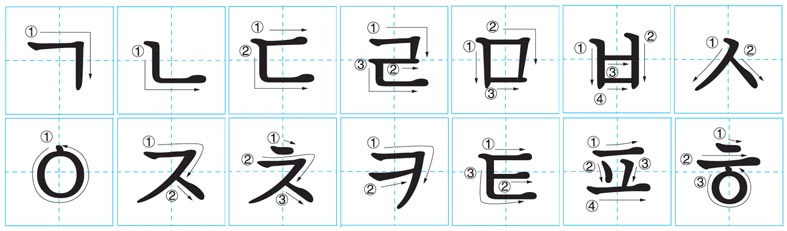

Consonants: What you see is what you write.

The shapes of consonants, ㄱ(g/k),ㄴ(n),ㅅ(s),ㅁ(m) andㅇ(ng), are based on how your speech organs look like when you pronounce these sounds. Other consonants were derived from the above letters by adding extra lines for aspirated sounds and by doubling the consonant for tense consonants.

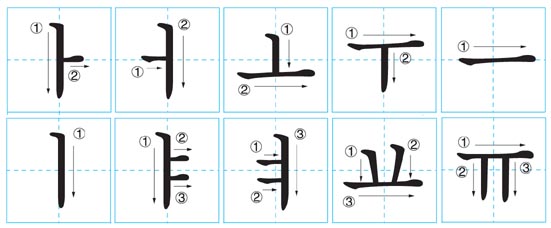

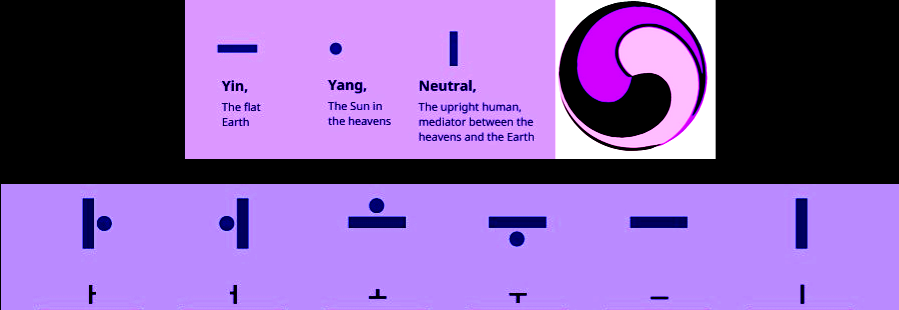

Vowels: Three strokes encompass the world.

Various combinations of three strokes make up vowels in Hangul. A horizontal line (ㅡ) represents the Earth (Yin), a vertical line for the standing human (ㅣ), and a point (ㆍ) for heaven (Yang). This concept is derived from Eastern philosophy where heaven, Earth and human are one.

Vowel combinations in Hangul

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AHangul_Taegeuk.png

By Jatlas (Own work) [CC BY-SA 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

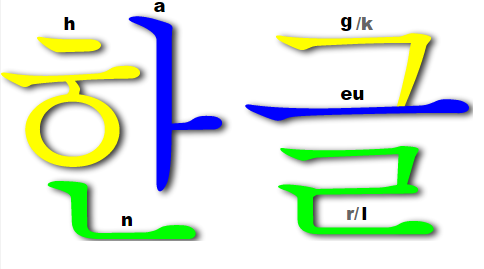

The Korean alphabet consists of 14 consonants and 10 vowels. Unlike English, where letters are written in sequential order, Korean letters are combined into syllable blocks. Each block produces 1 syllable. A syllable block contains a combination of consonant/s and vowel/s. For example, since the word 한글 (Hangul) has two syllables, it has two blocks. Pretty easy, right?

Syllable Blocks for the word 한글 (Hangul)

http://allthingslinguistic.com/post/66133111314/why-the-korean-alphabet-is-brilliant

Learn Korean

If you have made it this far, you may want to check out some ways you can actually learn the language yourself. There are numerous resources and classes that will fit your learning style.

Take classes:

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign offers twelve Korean language courses throughout the academic year with varying levels. There are multiple scholarship opportunities for learning Korean! Check out Foreign Languages and Area Studies, Critical Language Scholarship Program, Middlebury Language Schools’ Summer Intensive Program Fellowship, and many more.

Self-study tools:

Strapped for time during the semester? There are many self-study tools that will let you learn the language in your own time, location and pace.

- Rosetta Stone – Online language learning program free through the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library.

- Italki – Website that connects language learners with online teachers.

- Talk to me in Korean (TTMIK) videos and podcasts – Contains more than 1,000 free audio and video lessons along with textbooks, workbooks and e-books available for purchase.

- Defense Language Institute’s Korean Course – Free online language course offered by Defense Language Institute.

- Indiana University’s Center for Language Technology Korean Language Program – Provides online activities for various levels of Korean.

- Hello Talk – Language App available for iOS and Android where you get instant connection to native speakers from around the world.

Print resources:

- Integrated Korean Series – Want to take a peek at what students are learning in Korean classes? This is the current textbook used by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Korean Language Program.

- 서강 한국어 (Sŏgang Han’gugŏ) – Series of textbooks published by Sŏgang University in Korea and used by many Korean programs in American Universities.

- 재미있는 한국어 (Chaemi innŭn Han’gugo) – Korean textbook series published by Korea University. Volumes 4-6 are available through the University Library.

- Everyday Korean Idiomatic Expressions: 100 Expressions you can’t live without – Have you ever wondered about some Korean expressions from K-drama that just did not do it justice with word-for-word translations? Well, this book is for you! This book lists 100 idiomatic expressions with literal and actual meanings and usages with detailed explanations so you can be a Korean language expert. Here is the book intro.

- 외국인을 위한 한국어 읽기 (Korean Graded Readers) – Want to read Korean novels and short stories but afraid that those may be too hard for you? Here is a set of 100 books where Korean novels and short stories are divided into levels of difficulty.

- Korean with Chinese Characters – Want to find out how Hancha (Chinese characters in Korea) is used in a Korean context? Here is a book that lists some common Hancha words used in Korean contexts.

Language through media:

Sometimes, learning a language may be less stressful if you follow a storyline. Here are some resources for you to explore Korean movies and dramas.

- Media Collection at Undergraduate Library – Korean movies from diverse time periods are available through the Media collection at Undergraduate library.

- Asian Educational Media Service (AEMS) – AEMS is a program of the Center for East Asian and Pacific Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign that offers multimedia resources to promote awareness and understanding of Asian cultures and people.

- Asian Film Online – Asian Film Online offers a view of Asian culture as seen through the lens of the independent Asian filmmaker. Through a selection of narrative feature films, documentaries and shorts curated by film scholars and critics, the collection offers perspectives and insights on themes highly relevant across Asia, including modernity, globalization, female agency, social and political unrest, and cultural and sexual identity.

- Ondemandkorea.com – Watch Korean drama and variety shows, for free. Many of the episodes provide subtitles in English and Chinese.

Other Resources:

- Korean Language Program -The Korean Language Program at University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign offers Korean and accelerated Korean language course tracks for non-heritage and heritage learners. These language courses are augmented with cultural instruction introducing students to both Korean culture and society using authentic texts and audio-visual materials including newspaper articles, dramas, films, documentaries, etc. Weekly events such as the Korean Conversation Table (KCT) are available during the semester to help you practice speaking in Korean.

- Center for East Asian and Pacific Studies (CEAPS) – The Center for East Asian and Pacific Studies provides lectures, seminars, programs and events on East and Southeast Asia.

- Korean Cultural Center (KCC) Facebook Page – The Korean Cultural Center is a registered student organization and a non-profit organization at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. The group works to promote Korean culture through various events and programs. Visit their Facebook page to check out the latest event!

If you are interested in finding out more about learning Korean language or its culture, feel free to contact the International and Areas Studies Library at internationalref@library.illinois.edu. Also, don’t forget to follow our Facebook page for instant updates on cultural events and posts like this one.

Author: Audrey Chun

References

Algi Shwipke Pʻurŏ Ssŭn Hunmin Chŏngŭm. Sŏul : Saenggak ŭi Namu, 2008.

“The Background of the invention of Hangeul”. The National Academy of the Korean Language. January 2004.

Hunmin Jeongeum Haerye, postface of Jeong Inji, p. 27a, translation from Gari K. Ledyard, The Korean Language Reform of 1446, p. 258.

Korea. [Seoul : Korean Culture And Information Service], 2008.