Japanese architect Yamamoto Riken has been awarded 2024’s prestigious Pritzker Architecture Prize, recognized as one of the highest accolades in the field. Born in Beijing, China, in 1945, to an engineer father (part of the occupying force) Yamamoto’s early years were shaped by the aftermath of the Asia Pacific War. His family relocated to a war-torn Tokyo in 1947, where he witnessed firsthand the rebuilding process, sparking his interest in the symbiotic relationship between architecture and community.

After completing his studies at Nihon University and Tokyo University of the Arts, Yamamoto established his architectural firm, Riken Yamamoto & Field Shop, in 1973.

Among his notable works are the Yokosuka Museum of Art, situated on Tokyo Bay, and the transparent Hiroshima Nishi Fire Station. These projects reflect Yamamoto’s characteristic use of open space. He employs extensive use of glass to make the insides of buildings more visible. His buildings can be seen all over the world.

Hiroshima Nishi Fire Station

To explore his work, see:

https://www.pritzkerprize.com/laureates/riken-yamamoto#laureate-page-2591

http://www.riken-yamamoto.co.jp/index.html?lng=_Eng

For more information about his Pritzker Prize win see

https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/backstories/3126/

https://www.npr.org/2024/03/05/1232854692/riken-yamamoto-pritzker-architecture-prize

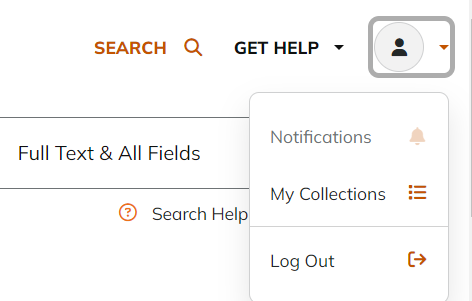

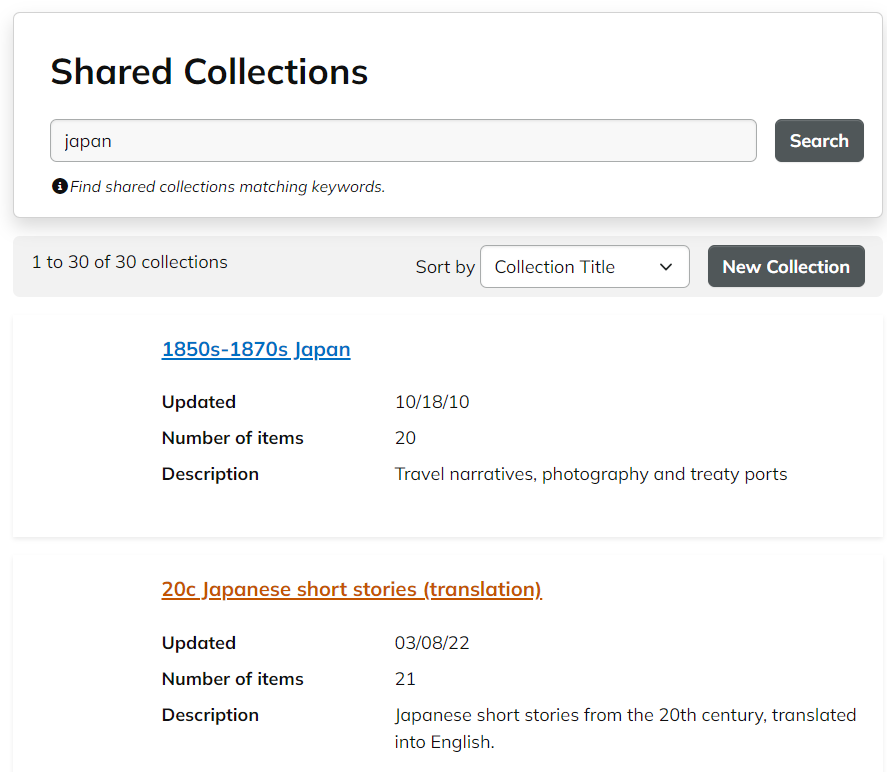

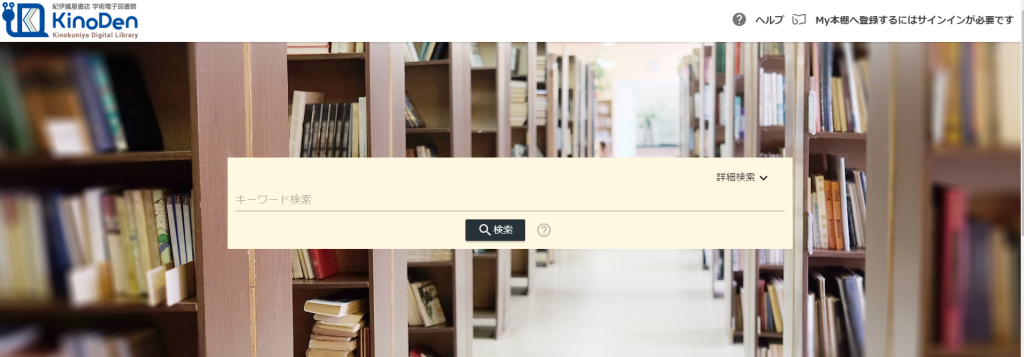

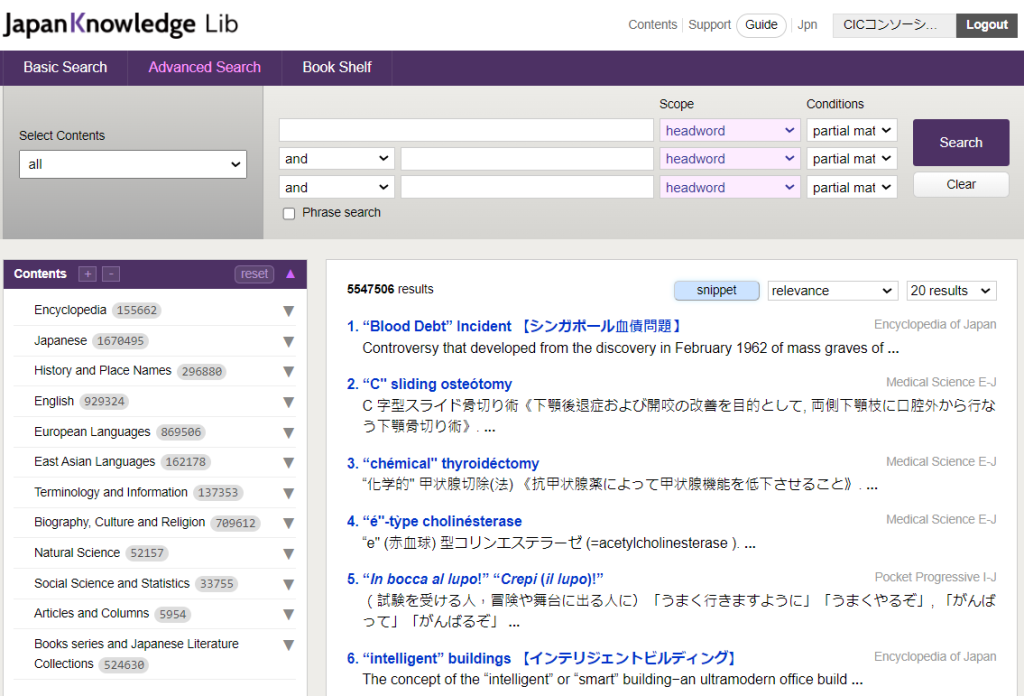

To explore more about Riken Yamamoto at the University of Illinois Library see:

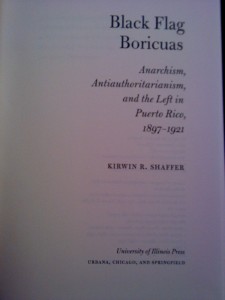

Main Stacks: Q. 720.952 Y145ri

How to Make a City, was published to accompany an exhibition at the Architecture Gallery Lucerne. It is a selection of projects from the office Riken Yamamoto, including The Circle at Zurich Airport. “The book focuses on Yamamoto’s long-standing engagement with the concept of ‘city’ and the modern demands of urban life, given increasing population.” (book jacket)

Klauser, Wilhelm, and Riken Yamamoto. Riken Yamamoto. Basel ; Birkhäuser, 1999.

Architecture and Art Library: Q. 720.92 Y14k:E

Architectural critic Klauser Wilhelm closely examines Yamamoto’s architecture. “In his architecture, Yamamoto is trying to account for changes in society, such as the dissolution of the basic family unit or new education programs, by developing the appropriate ground plan concepts. This publication documents Yamamoto’s manner of working and the persistent optimization of his architectural program by presenting twelve of his buildings.” (book jacket)

Yamamoto Riken, Shisutemuzu sutorakuchua no ditēru. Tōkyō-to Shinjuku-ku: Shōkokusha, 2001.

Oak Street Library: Q. NA1559.Y36 A4 2001

Shisutemuzu sutorakuchua no ditēru or Details of System Structure, by Yamamoto Riken, explores his architecture. It is an oversized artbook with detailed photos of his architecture.

Architecture and Art Library: 720.952 Y145r

Yamamoto Riken no Kenchiku, or The Architecture of Riken Yamamoto is a monograph authored by Riken Yamamoto, chronicling 34 years of architectural philosophy and his outlook on the future of the field. This book showcases 29 projects, including Yamakawa Villa in Nagano, Fujii House in Kanagawa, Yamamoto Mental Clinic in Okayama, and Saitama Prefectural University amongst others. Including sketches, blueprints, and photographs, it offers an exploration of Yamamoto’s past and present architectural endeavors.

Lib Guides