The University of Illinois Library holds one of the largest and most referenced Japanese Studies collections in North America. Recently, our collection has grown even larger with the inclusion of many online academic resources from Japan or in the Japanese language. These valuable additions were made possible through several cross-institutional digital repositories. With the rapid growth of digitized and web-published materials, academic institutions worldwide are now collaborating to build digital libraries and share data. This collaboration enables libraries to increase accessibility to electronic resources more efficiently. Here are some noteworthy additions to our collection.

The ERDB-JP Project

The ERDB-JP project, established by the Council for Promoting Collaboration between University Libraries and the National Institute of Informatics, has included 211 partner institutions across Japan to date. The digital resources shared by partner institutions mainly consist of e-journals and e-books in the Japanese language or published by entities based in Japan. Currently, all the data registered in ERDB-JP are open to the public under the CC0 1.0 Universal license. This license allows users in Japan and abroad to search, browse, and download materials.

As of October 2023, the open knowledge base has over 44,000 registered titles, and the number continues to increase significantly. In addition to searching for resources on the ERDB-JP website, UIUC users can also access e-books and e-journals through the University Library’s online catalog. Many titles from ERDB-JP are now searchable in our catalog and can be accessed in full text by clicking on “Freely Accessible Japanese Titles.”

HathiTrust

HathiTrust is a collaborative digital library that brings together an extensive collection of books, journals, and other materials from over seventy libraries and research institutions worldwide. It plays a vital role in facilitating research, education, and providing equitable access to knowledge, especially since the Covid-19 pandemic. As a partner institution of HathiTrust, the University of Illinois Library has integrated titles from HathiTrust into our online catalog, allowing affiliated users to download full texts of resources in the Public Domain or with a Creative Commons license.

Keio University, as the sole participant from Japan, has made a valuable contribution to Japanese e-resources to the digital library. These titles, along with materials from other partner institutions, have significantly expanded UIUC’s digital Japanese collection.

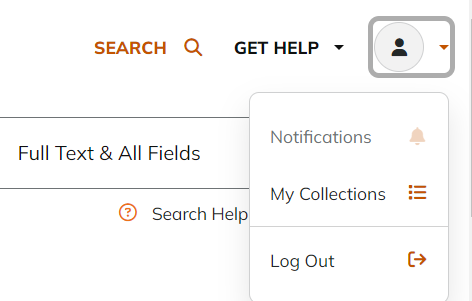

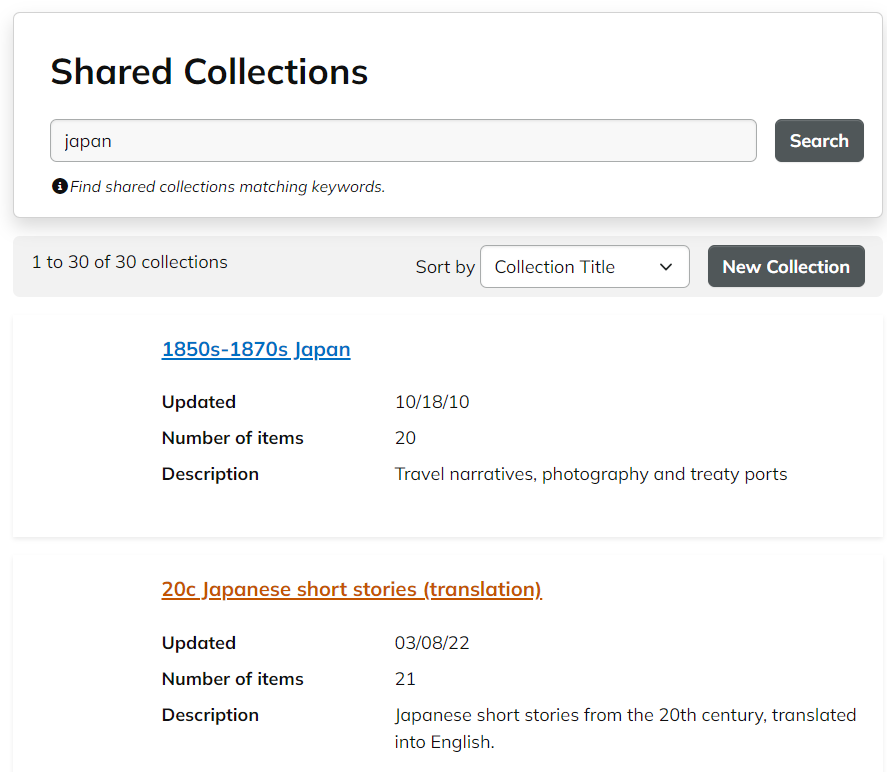

In addition to accessing e-books and e-journals in Japanese through the University Library’s catalog, we also recommend users explore the shared collections within the HathiTrust corpus to find more resources related to their research interests. HathiTrust allows users to organize, save, and share titles from its repertoire. To do this, UIUC users can click on the “Log in” button at the top right and select our institution. After logging in, you can access all Shared Collections by selecting “My Collections” from the top-right drop-down menu. Various Japan-related collections have already been created, including “Newspaper articles about Japanese Americans during and after WW2,” “Japanese Literature,” “The Spirit of Missions,” “Azuchi-Momoyama,” “Books in English on Japan, 1815-1945,” and more.

If you want to explore more useful functions of HathiTrust, the UIUC HathiTrust LibGuide will provide the best reference for you.

KinoDen

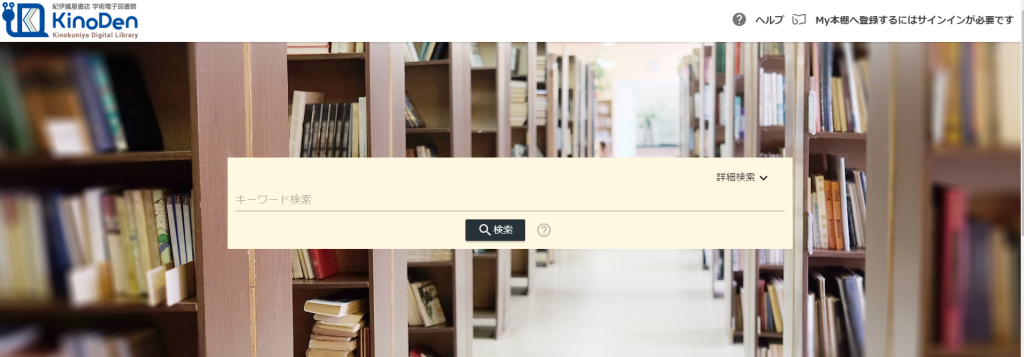

KinoDen, short for Kinokuniya Shoten gakujutsu denshi toshoka (“Kinokuniya digital library”), is an e-book service that provides access to academic Japanese books. A direct link can be found by searching “KinoDen” in the University Library’s catalog. By clicking “view full text,” users will be redirected to KinoDen’s main page where they can search for books using the toolbar.

The University Library has purchased part of KinoDen’s collection, which can be viewed in full text. For titles that are not available for UIUC users (labeled as 未所蔵), we can still access the bibliographic metadata and free samples. In addition to using the KinoDen database, users can also find purchased titles in the University Library’s catalog.

More detailed instruction on how to use KinoDen is now available in the LibGuide Using KinoDen, created by the International and Area Studies Library.

Japan Knowledge Lib

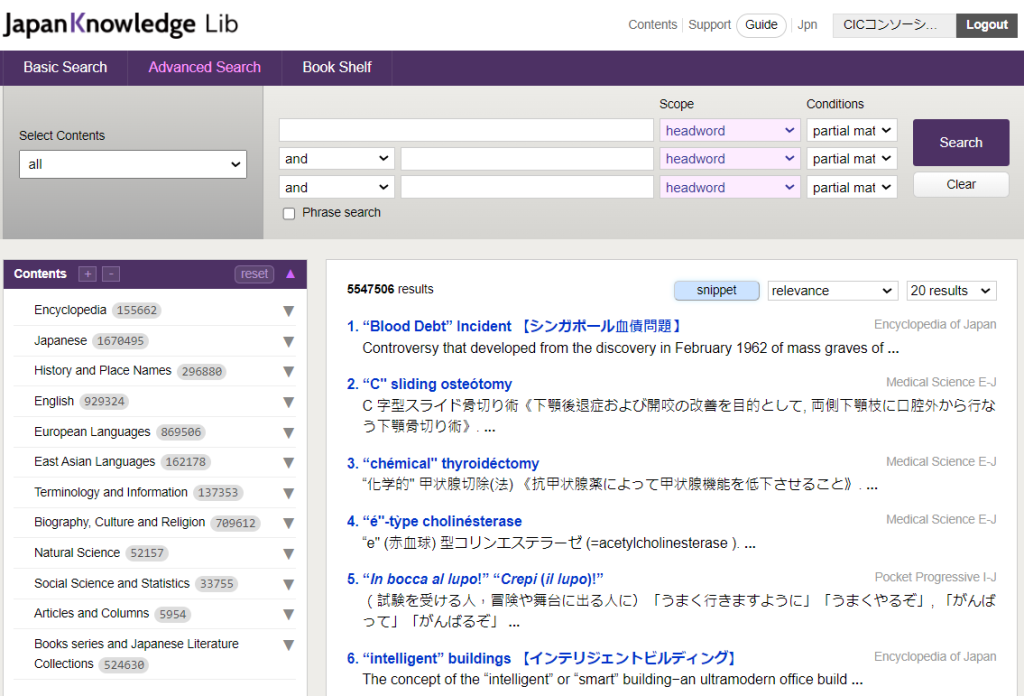

JapanKnowledge Lib is a diverse digital collection of encyclopedias, dictionaries, journals, and reference works. These resources are now searchable and accessible in full text through the University Library’s catalog. UIUC users also have the option to log in to the JapanKnowledge website to cross-search contents in the database.

Have more questions about how to use JapanKnowledge? The International and Area Studies Library has published the How to Use JapanKnowledge+ LibGuide, which provides instructions for searching and a comprehensive content list!

Meiji Japan: The Edward Sylvester Morse Collection from the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum

Last but not least, the library has an expanding collection of Japanese e-archives. Here, we would like to highlight “Meiji Japan,” a collection that encompasses Edward Sylvester Morse’s contributions to zoology, ethnology, archaeology, and Japanese art, as well as detailed records of daily life in late 19th-century Japan.

Edward Sylvester Morse (1838-1925) was an established scholar in natural history and Japanology. In the 1870s and 80s, he made multiple visits to Japan and extensively documented the lives of the Japanese people. His work captured a crucial period in Japanese history, just before Western civilization brought significant changes to the country. In 1926, 99 boxes of his personal and professional papers were donated to the Peabody Essex Museum and have since become one of North America’s most notable archives in Japanese studies.

In recent years, the Peabody Essex Museum has digitized Morse’s papers and created the online database “Meiji Japan: The Edward Sylvester Morse Collection from the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum.” UIUC Users can access the database through the University Library’s website and search for individual items in the library catalog.