An Educational Guide to Optimize the Preservation of Time Capsules

by Dani Demmerle, Preservation Services Grad Assistant

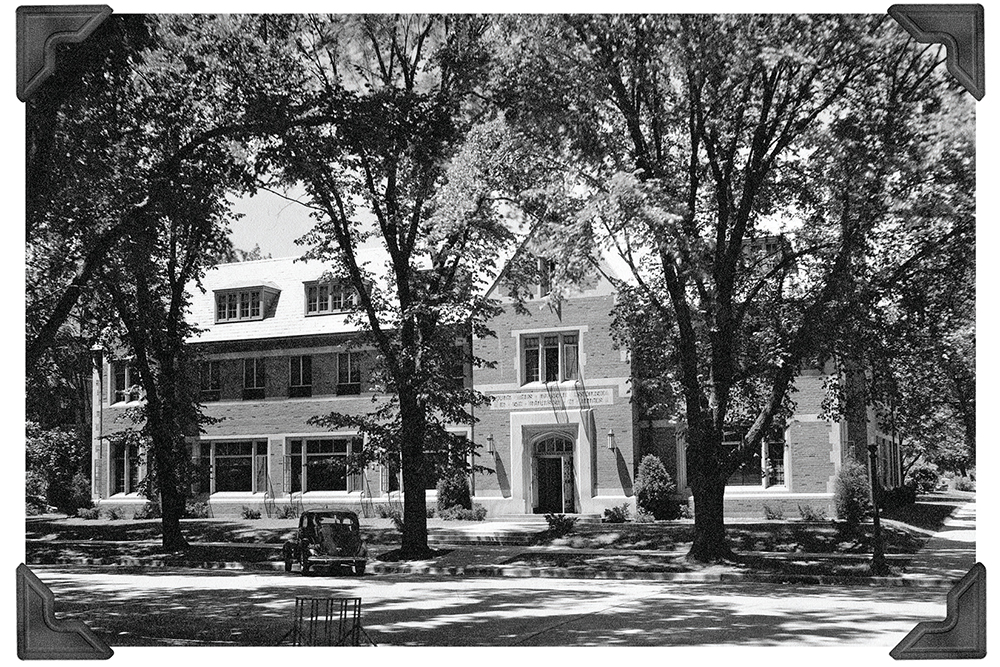

To explain the depth of this story we need to take a step back in time. In 1873, the University YMCA was founded, and in 1907 a new building was built to function as the organization’s headquarters. That building was named Illini Hall. During construction of Illini Hall, a time capsule was hidden in the cornerstone.

In February 2023 the demolition of Illini Hall was underway, beginning the plan for a new facility. During the building’s demolition, the time capsule was discovered inside the cornerstone. There were historical photos and documents that hinted at the possibility of a time capsule but there was no guarantee.

After the time capsule was discovered in February 2023, it was returned to the current YMCA Executive Director, Jim Hinterlong. The YMCA decided to hold off opening it until the fall of 2023 when the University YMCA would be celebrating its 150th anniversary. The time capsule was kept in a display case in the YMCA building, located at 1001 S Wright St.

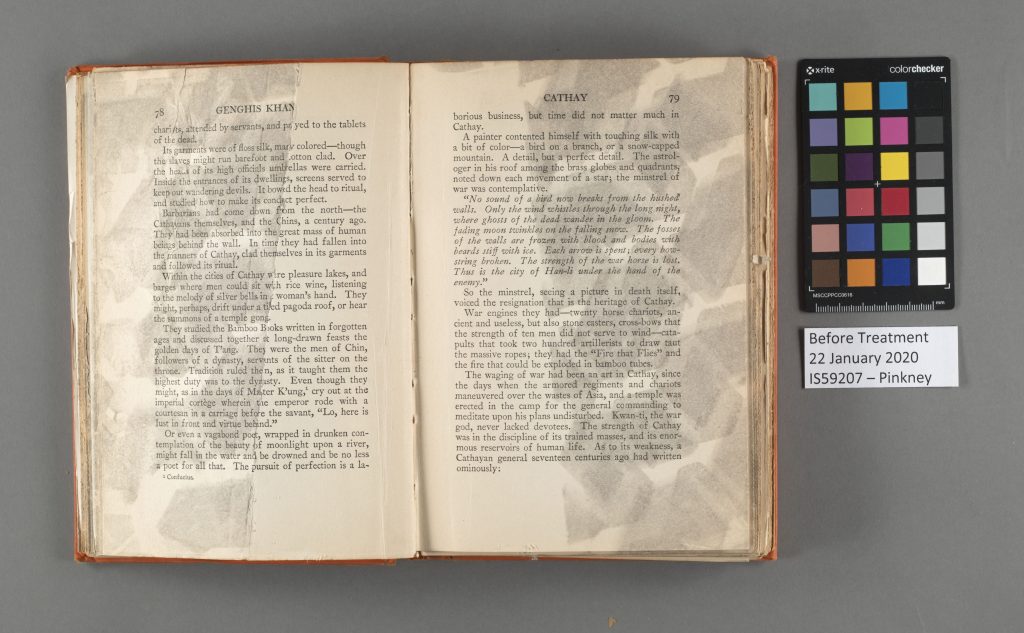

After unveiling the contents of the time capsule at the anniversary celebration, it was clear that professional attention would be needed. Jennifer Hain Teper, Head of Preservation Services at the University Library, was contacted by Jim Hinterlong to assess the time capsule and its contents.

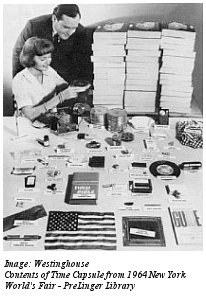

What’s Inside

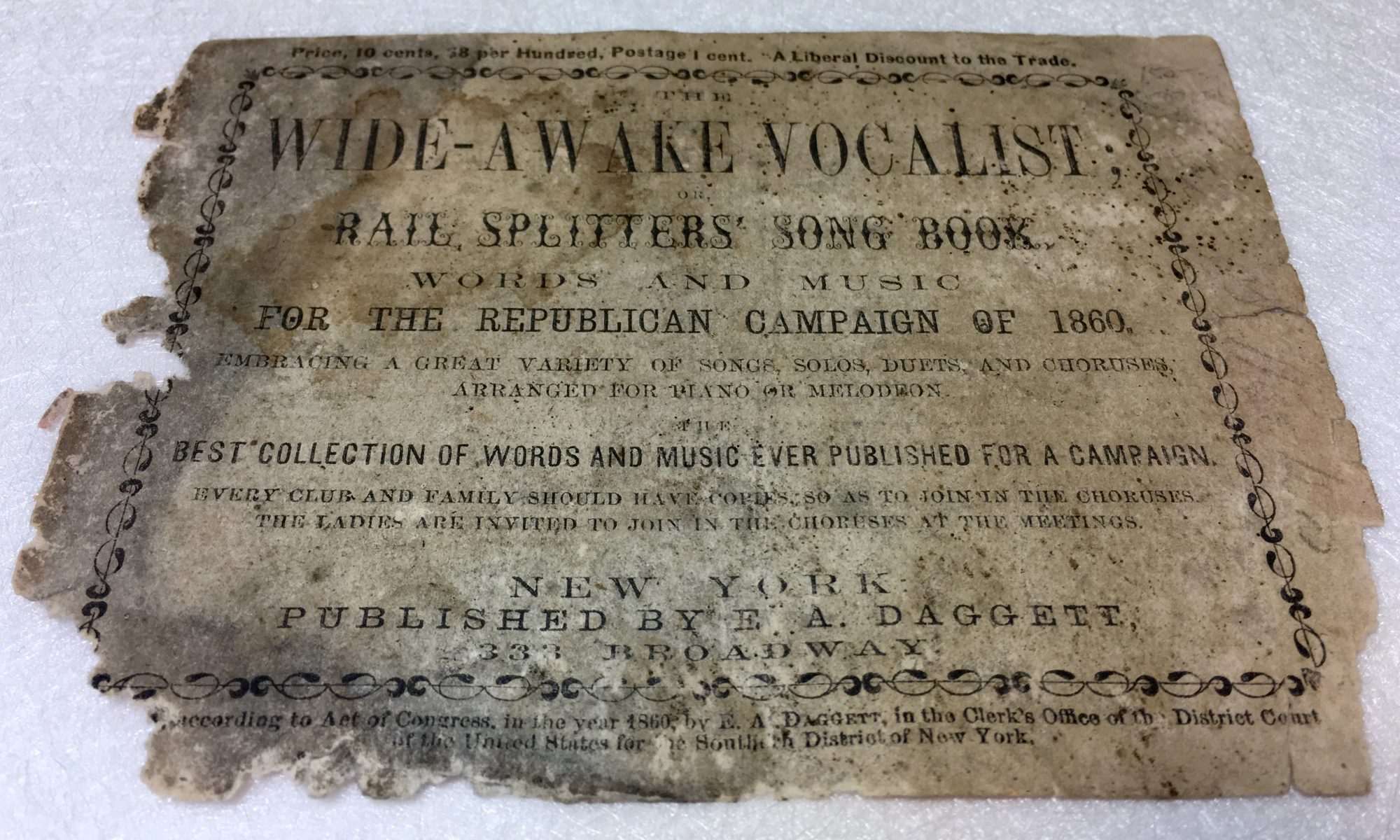

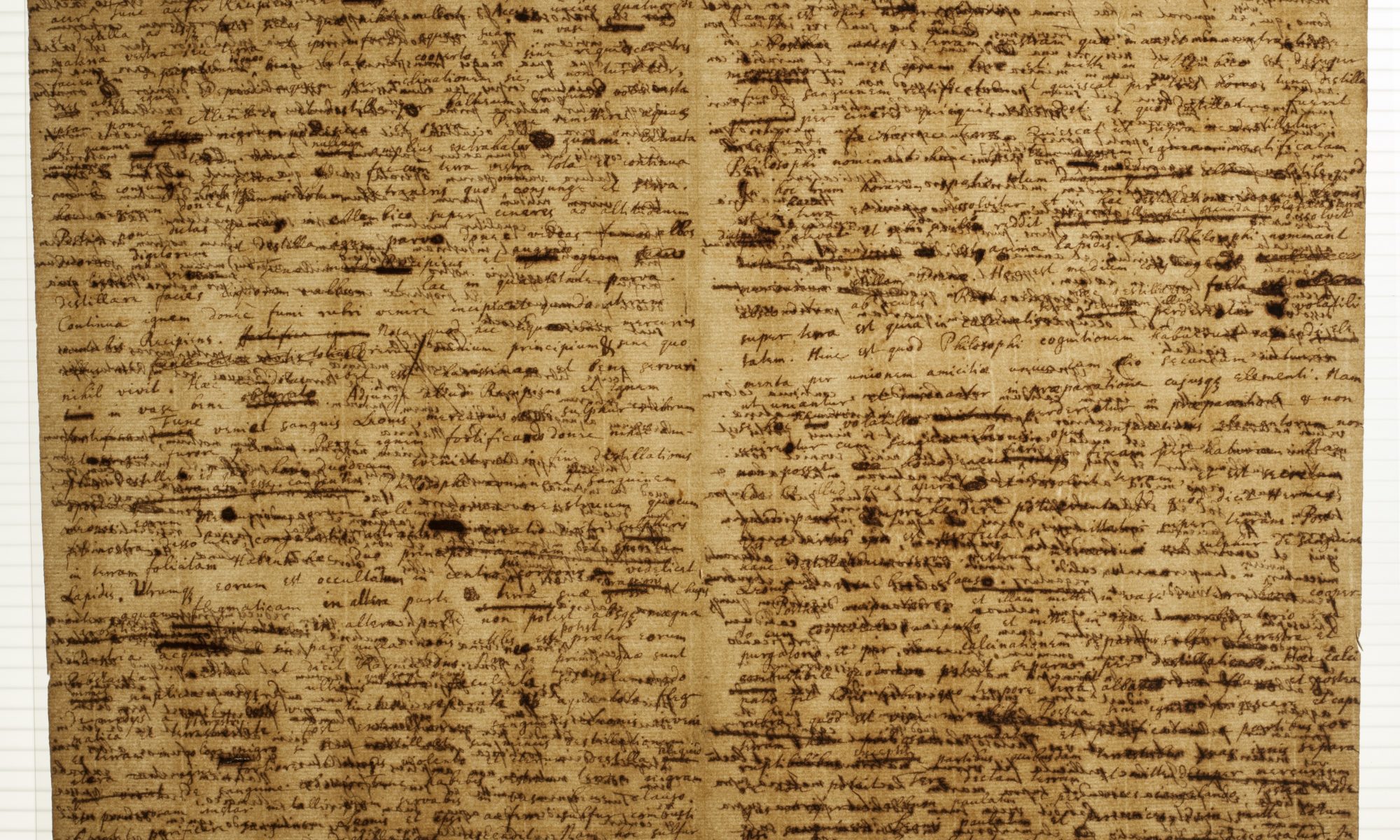

The time capsule itself was a heavy metal gauge box, possibly copper. Inside the metal box was a stack of paper-based materials. The materials on top of the stack were the most affected by age and elements. Fragmented into tiny pieces and incapable of being handled without more damage, the topmost material was unidentifiable. The remaining items were in far better condition, and able to be identified:

- YMCA annual Report of the General Secretary, ca. June 1907

- YMCA Founding Constitution, 1904

- The Illini, vol.36 [no.200], June 11, 1907

- University of Illinois Bulletin, vol.4 no.16, April 15, 1907

- The Champaign Daily Gazette, June 19, 1907

Jennifer and her associate Shelby Strommer, the University Library’s Collection Care Coordinator, assessed the items. Overall, the contents of the time capsule were in good condition, considering the items were in a wall for 116 years with no control over fluctuating temperature and humidity. Jennifer and Shelby were impressed with the condition of the newspapers that were at the bottom of the stack. The paper itself was intact and able to be unfolded without breakage. Many of the other materials had become brittle with age and the fluctuating conditions they were exposed to, but the newspapers were the exception.

It is difficult to speculate why the newspaper was in better condition compared to the other contents, but this is the magic of time capsules: you never know what will happen.

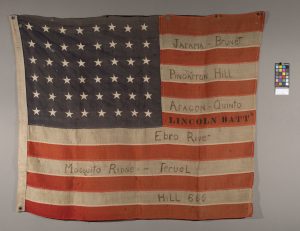

Strangers to Neighbors

More than ten years ago and just across the street from Illini Hall, less than 200 feet from where the time capsule was found, was another time capsule hidden inside the Alma Mater statue. This time capsule was removed in 2012 and replaced with a new one when it was discovered that the screw top glass jar used as the container exploded due to conditions it had been exposed to.

The Alma Mater time capsule was placed in the statue back in the 1980s. Between then and 2012, a gap near the base of the statue was patched. The cast bronze statue has seams throughout it where it was pieced together. These seams are not airtight, and water and moisture can get it. Without the proper drainage the water is trapped inside, heating and cooling with the seasons. The glass jar inside was locked in these conditions and caused the glass to eventually shatter, exposing its contents to the elements inside the statue.

The statue was removed in 2012 for conservation. When the statue was lifted away for transport, finding a time capsule, or what was left of it, was quite a surprise to Jennifer Hain Teper and Christa Deacy-Quinn, who were on the conservation project team. Since the glass jar time capsule was damaged, the University of Illinois Office of Public Affairs set a new one in its place. The new time capsule included a gold DVD, USB drive, UIUC t-shirt and the original items. A gold DVD was used since gold is one of the most inert, reflective elements on earth, which makes it perfect to resist the effects of temperature and humidity. These characteristics prevent oxidation, a common cause of failure for most DVDs. The items were sealed inside a stainless-steel preservation time capsule container. This container was made to be a time capsule and will do a better job of minimizing the impact of fluctuating temperature and humidity.

The Alma Mater statue’s conservation project included regular maintenance to prevent it from needing to be sent away, so there is no guarantee the second capsule will be seen again.

For 30 years these two time capsules were neighbors. With the discovery and removal of the YMCA time capsule, the time capsule in the Alma Mater statue is once again the only time capsule that we know about in the area.

Treasure Chest

The success of a time capsule depends heavily on the quality of the enclosure. If an improper container is selected, then the contents of the time capsule are more susceptible to the environment around it. There are many materials that can be used for time capsules, but a highly recommended container is one made of high alloy stainless steel. Ideally, the container should be of seamless or welded construction with a screw top and gasket to ensure it is suitable for long-term burial. You can find high quality, waterproof time capsules online by searching for “professional grade time capsule.” Containers like glass jars are cheap and accessible time capsules but do not have insulating properties. If mishandled they can shatter, completely exposing the contents to the environment.

Paper Doesn’t Get Claustrophobic

A common mistake in long-term storage of items, including time capsules, is that the contents are given too much room to breathe. Materials like paper that are hydroscopic absorb moisture from the environment and expand and shrink with changes in humidity. This causes the paper to warp and become brittle at an accelerated rate. Storing materials that are hydroscopic in snug, but not tight, containers can help reduce fluctuations in humidity, creating a more stable microclimate.

To Seal or Not to Seal

Next, let’s discuss sealing time capsules. If you have a professional grade time capsule, you might purchase a time capsule preservation kit to accompany it. These kits include desiccants, packs that absorb the moisture in the air to maintain a low humidity environment. You will often find them at the bottom of snack bags, because if too much moisture was introduced into a snack bag it would be trapped and cause mold to form. The same goes for time capsules, which is why sealing your time capsule can be tricky. If you seal your time capsule, make sure there is not excessive moisture in the container before sealing, and that the container itself is waterproof to avoid the formation of microclimates: 30 – 50% relative humidity is ideal. If you are using a box you have lying around, sealing it may not be the way to go. If moisture is introduced to a time capsule that is not sealed, then mold might not flourish since there is more air circulation. This is not a guarantee, and it is a tricky line to walk but factors such as these can make all the difference.

Location, Location, Location

When building a time capsule, so many decisions are made based on protecting the contents from the outside world and the degrading effects of time. The location you pick is one of the biggest decisions in this process. Many hide time capsules away where they won’t be disturbed, but even if the item is mortared into the walls of a building or welded inside a bronze statue, things can go wrong. Sometimes not having control over the space the time capsule is stored in can be its demise. But the mystery of locking it away is part of the fun too. If you are interested in burying your time capsule, in most areas a depth of 18 to 24 inches should suffice. This is the area between the top of the time capsule and the ground level. You want it to be deep enough down in the ground to get a stable temperature.

Extra Help

If you are looking for extra help with your time capsule, there are time capsule preservation kits available online to better protect the contents from the inside. Kits include archival-quality paper (which may be buffered to slow the creation of acids) envelopes, folders, or boxes; uncoated PET zipper bags; or glass or stable plastic vials with screw-top lids. It is recommended that the time capsule’s contents are put into these containers individually or grouped with like items. Desiccants, as mentioned above, will help with moisture control. Desiccant packs usually last 1-3 years depending on the size.

Last Thoughts

Everything covered in this article depends on you. This is your time capsule, and it will be up to you to decide what your motivations are for it. Is your goal to make a highly secure modern time capsule that will protect the contents? Then purchase a professional grade time capsule and preservation kit. Or are you looking to make memories with loved ones, and you are more interested in the fun that comes with the journey? Then a shoe box might just be the capsule for you. Time capsules are an excellent way to capture time in material form to be unveiled in the future. Although there are plenty of resources today for optimal time capsule success, there have been many century-old time capsules that have endured the tests of time despite the conditions and factors working against them.

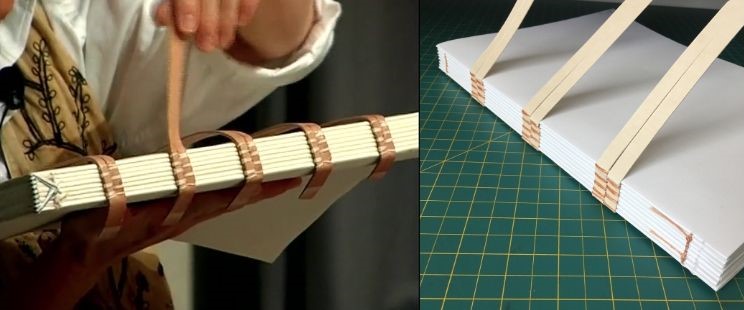

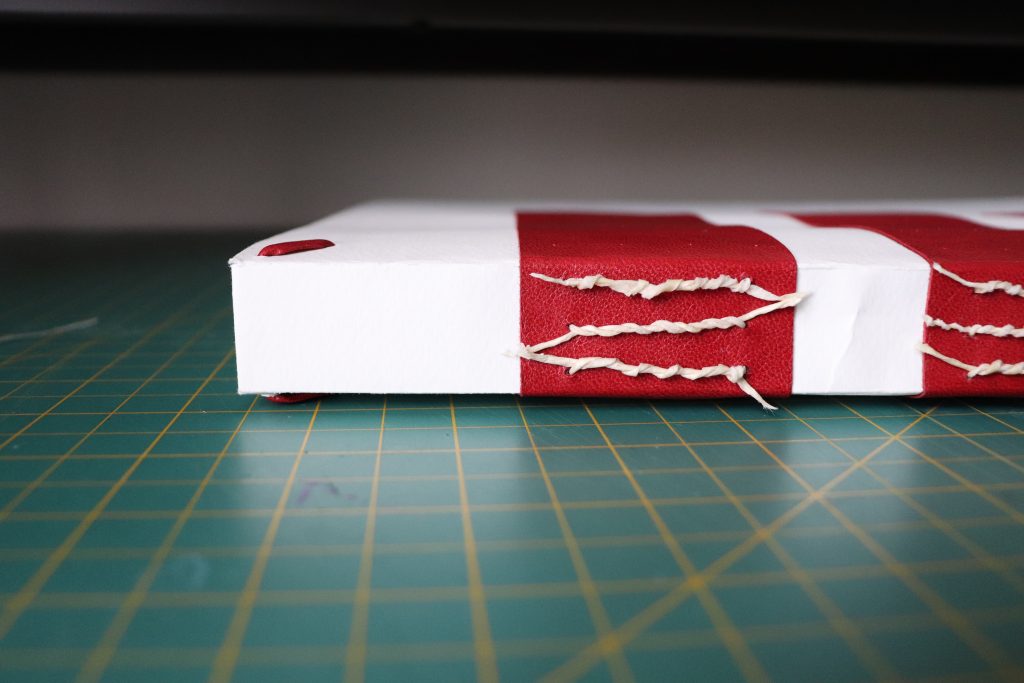

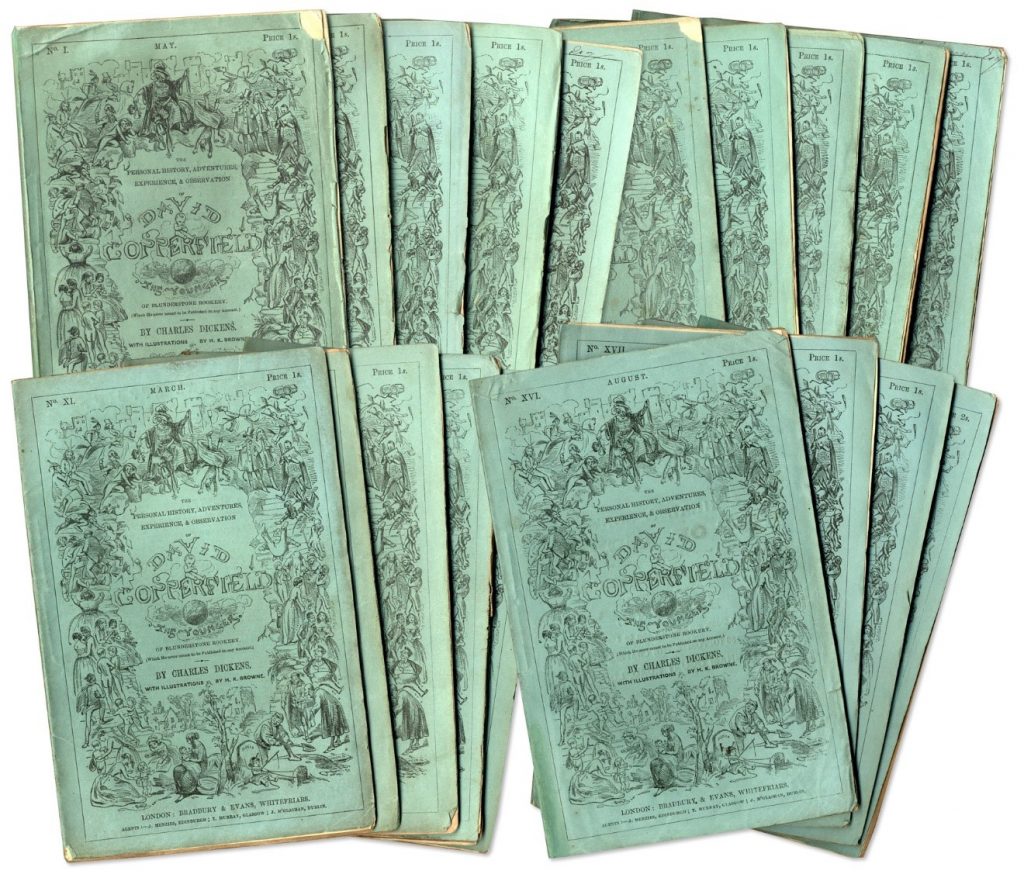

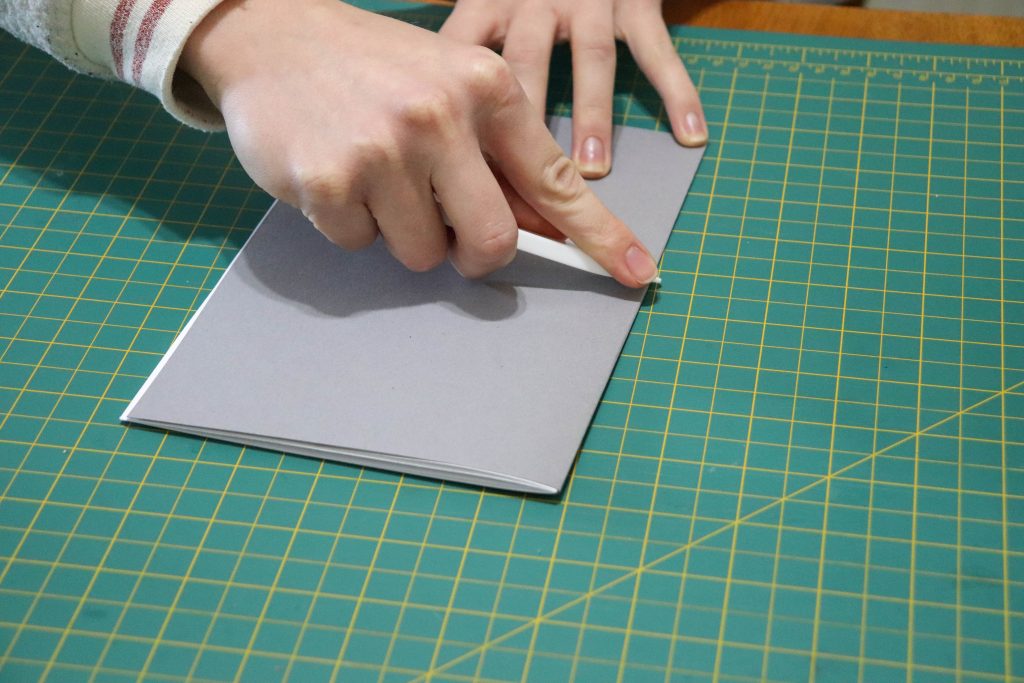

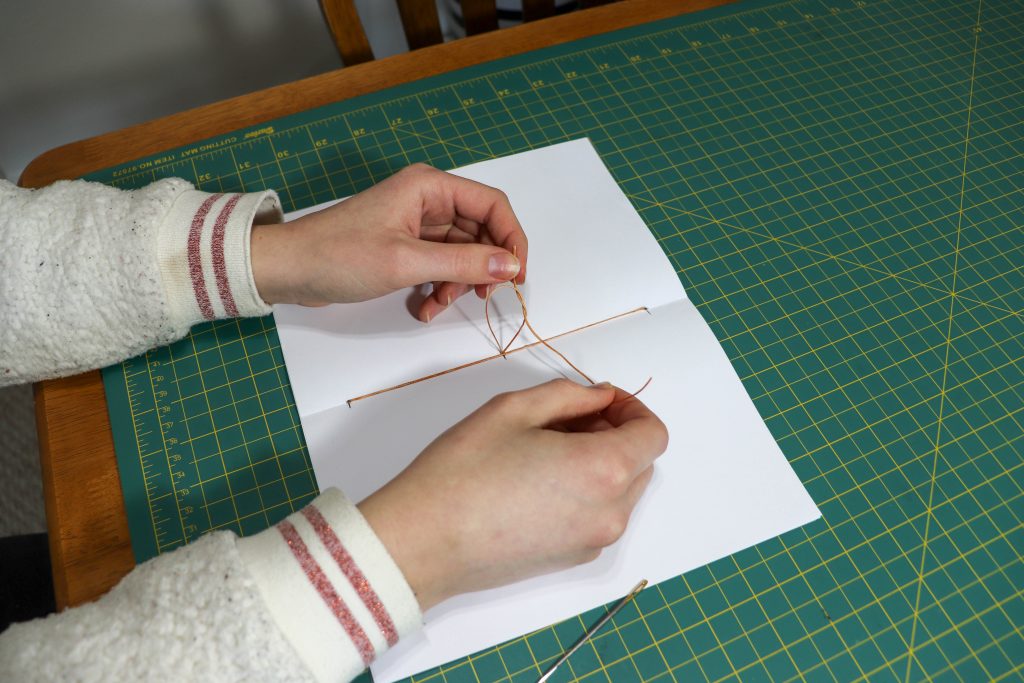

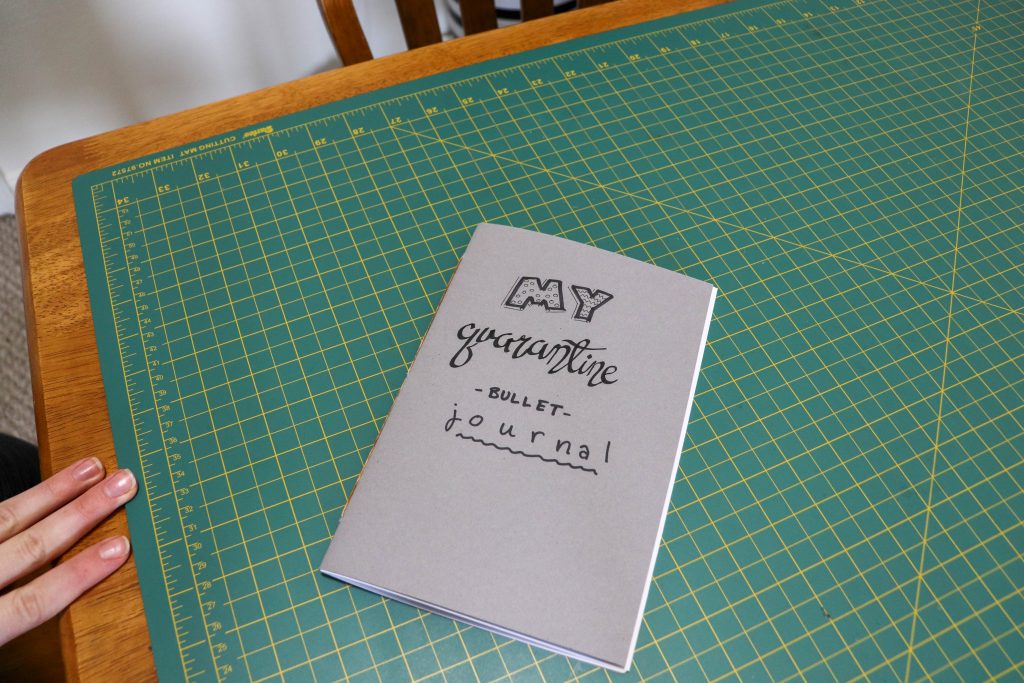

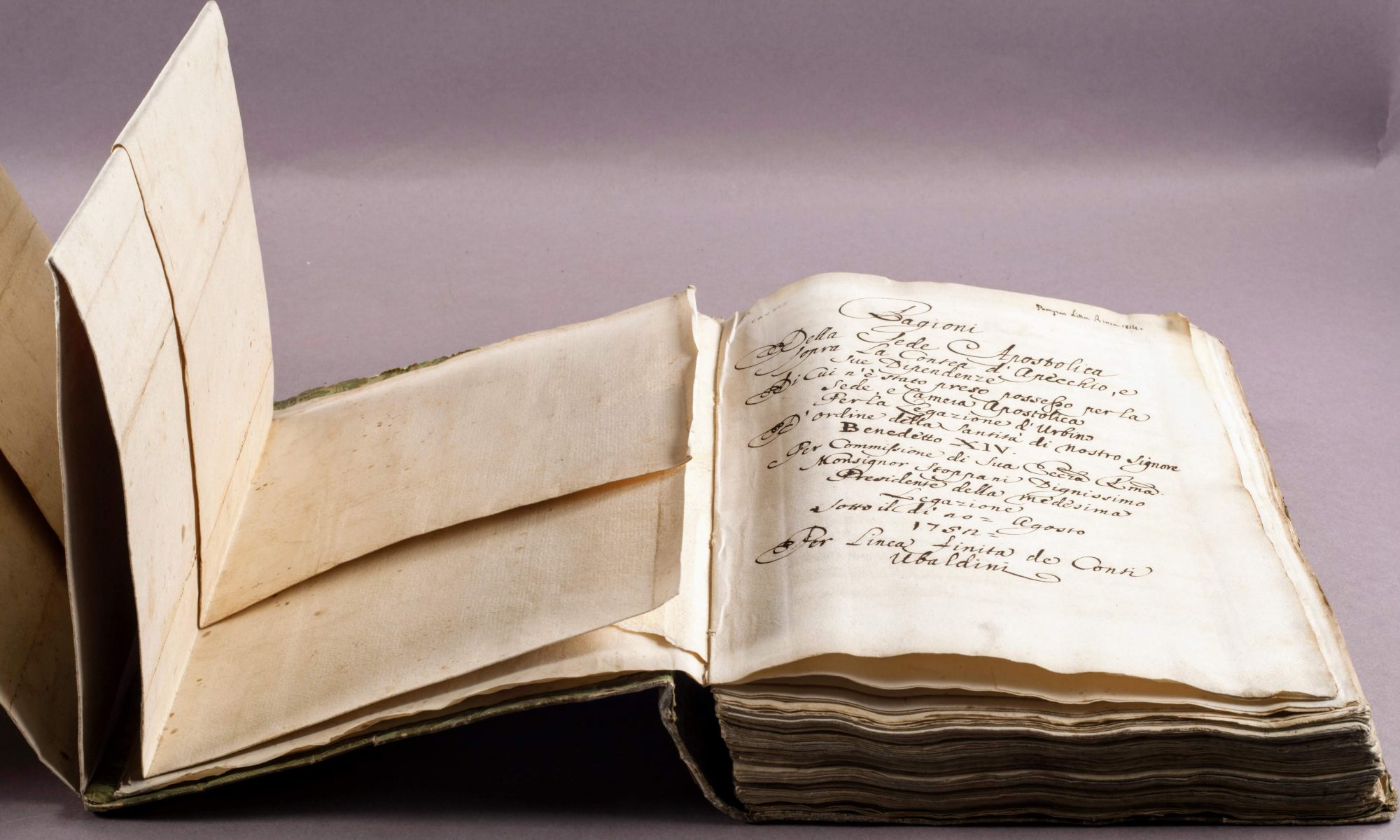

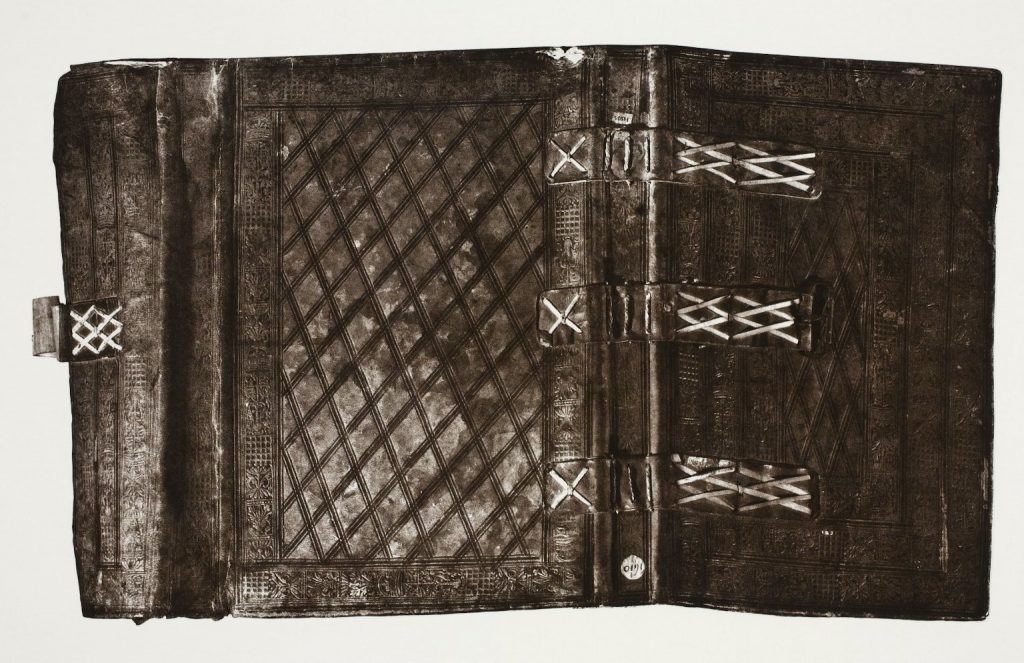

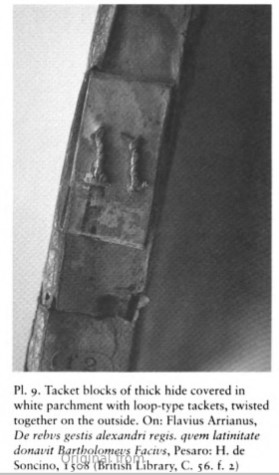

In the 1500’s, books were not necessarily produced as they are today. Books were sometimes sold as sewn blocks of printed pages without a case. After purchasing a text-block, one could hire a binder to design and build a case for their book with hard covers (usually made of wood). Depending on the wealth of the owner and the importance of the book, the case could be very fancy (e.g. a full leather covering with gold tooling and bosses). But until the owner of the text-block had the means and intention to have it cased in boards, the text-block could be temporarily secured in a limp case of vellum or leather – like a tacket binding! This provided simple and quick protection for their new purchase.

In the 1500’s, books were not necessarily produced as they are today. Books were sometimes sold as sewn blocks of printed pages without a case. After purchasing a text-block, one could hire a binder to design and build a case for their book with hard covers (usually made of wood). Depending on the wealth of the owner and the importance of the book, the case could be very fancy (e.g. a full leather covering with gold tooling and bosses). But until the owner of the text-block had the means and intention to have it cased in boards, the text-block could be temporarily secured in a limp case of vellum or leather – like a tacket binding! This provided simple and quick protection for their new purchase.