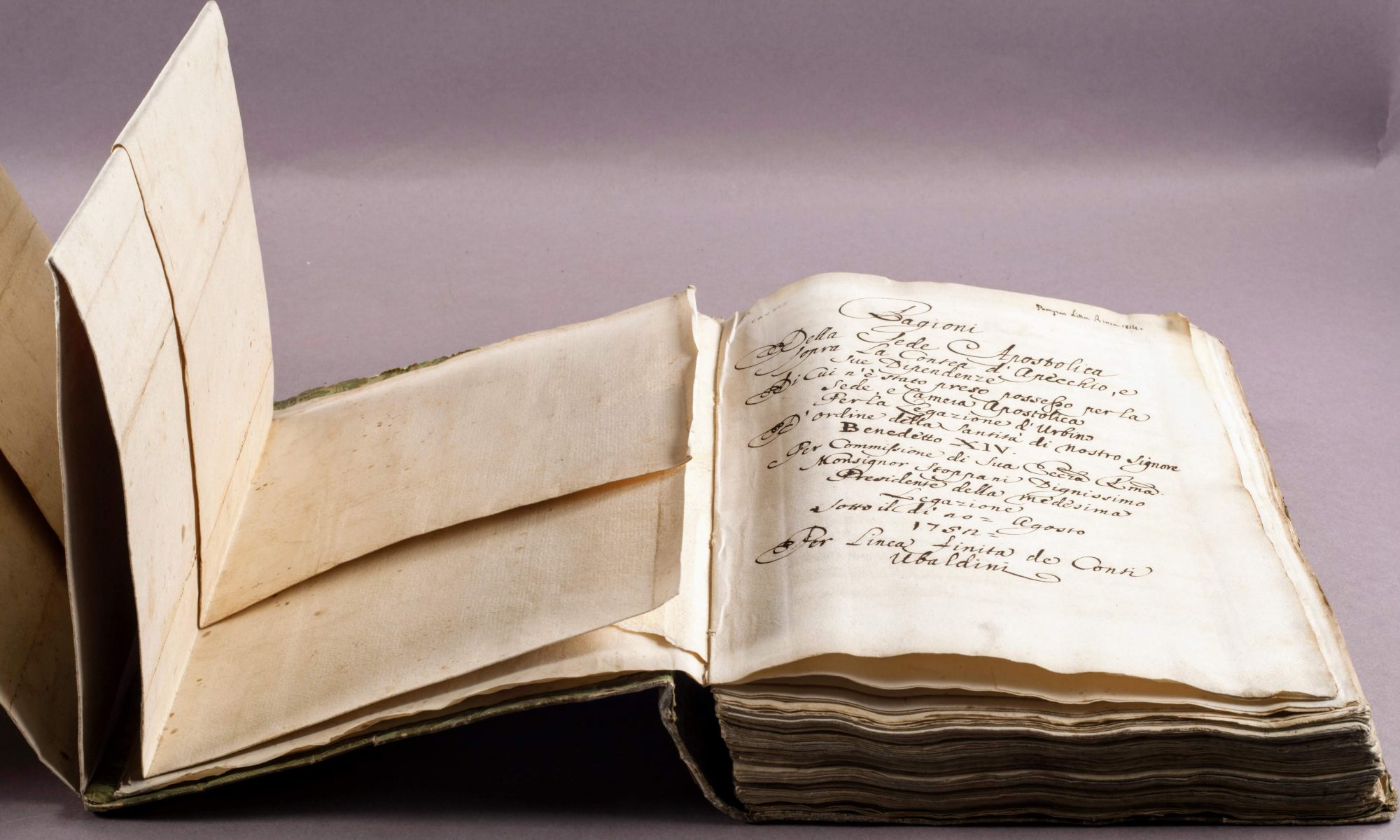

It is amazing to work at an institution that acquires so many interesting objects for its collection. A recent acquisition to our Rare Book and Manuscript Library is Sir Isaac Newton’s Latin translation of “Opus Galli Anonymi” in April 2018. While a fascinating piece for researchers, this antique manuscript needed some conservation help.

In case you fell asleep in science class frequently in school, here is a brief biography of Sir Isaac Newton.

In addition to being a brilliant mathematician, Newton was fascinated with alchemy and discovering the Philosopher’s Stone – a substance said to turn any base metal into gold. According to Wikipedia, 10% of his writings were dedicated solely to the Philosopher’s Stone. Thus, this manuscript was a treasured part of Newton’s collection. So how did the lab take on a 17th-century manuscript?

An important thing to remember about Preservation and Conservation is that not all objects necessitate invasive treatments. Invasive treatments can include washing, tape removal, utilizing solvents, or changing the book structure. Choosing to perform these types of treatments on an object requires careful consideration by conservators. While it is nice to provide restorative, cosmetic treatments, conservators also do not want to risk damage to the object.

Therefore it was decided for the Newton Manuscript to forgo invasive treatments for now and instead focus on creating a stable housing piece for it. Quinn Ferris, Senior Conservator at the Lab, was tasked with this undertaking. We sat down with Ms. Ferris to find out her experience with the manuscript.

What has been your role with the Newton Manuscript?

Part of the mission statement of the University Library’s Preservation Services Department is to maximize the library’s investments in its collections. When we acquire an important and valuable document, it is imperative that we have early discussions about planning for its long-term care. In the case of the Newton, Lynne Thomas and the Rare Book and Manuscript Library engaged with me early to discuss the potential needs and risks associated with Newton’s Translation of “Opus Galli Anonymi.” Because this is an important and exciting new acquisition, it was a priority to provide access to the manuscript as soon as possible upon its arrival by creating safe, well-fitting custom housing to support it. Therefore, my first concern was making a nice drop-spine box, both worthy in the appearance of the document as well as user-friendly. Apart from the rehousing, there have been additional discussions about the necessity for conservation treatment and a long-term care and handling plan, which will be prioritized after RBML has had the opportunity to provide access for some time. Collectively, we want to be sure we are doing everything we are able so that Mr. Newton’s manuscript can live a long and happy life within RBML’s collections.

What were your thoughts when you heard about this manuscript coming to Illinois?

To be honest, I didn’t know it was coming until it was here! One day during my office hours within the RBML, Lynne asked me to take a look at a recent acquisition. It took reading and re-reading the accompanying paperwork to be sure what I was looking at. Not sure how I missed the memo! Because acquisition and collection development is reliant on the expertise of our knowledgeable curators and often involves a lot of moving pieces that we in preservation don’t have an automatic role in, often conservation is not involved in working with an object until after it has arrived. I’ll tell you what though–

the day when you show up to work and a Newton Manuscript is unexpectedly waiting on your bench for examination is a pretty good day.

That’s why I love this job–you never know what you are going to find.

How did you decide on rehousing the manuscript?

Initial designs for the box for the Newton Manuscript started with a conversation between myself and Lynne Thomas. Lynne wanted a drop spine box covered in brown Canapetta book cloth that would be consistent in look to the book boxes in the rest of the collection. This condition alone removed the necessity of considering a wide range of approaches and materials. With that basic image in mind, we also discussed the ways in which we could make this particular box a little more special to suit the exceptional nature of this particular object. Adding marbled paper interiors and a silk ribbon were also suggestions that came from Lynne. With these parameters, it was my job as box maker to adhere to the desired aesthetic requirements as well to engineer the box to make sure that it was doing its job–protecting the manuscript from unnecessary additional stress or damage that can occur during handling or transportation to and from its home on the shelf. And that conversation was continuous as needed throughout the construction and completion–just days before the box was finished, I was bouncing potential title label designs off of Lynne for input and final approval. So in that sense, the decision-making around rehousing was a very collaborative process.

What did you take into consideration when creating a container for the manuscript?

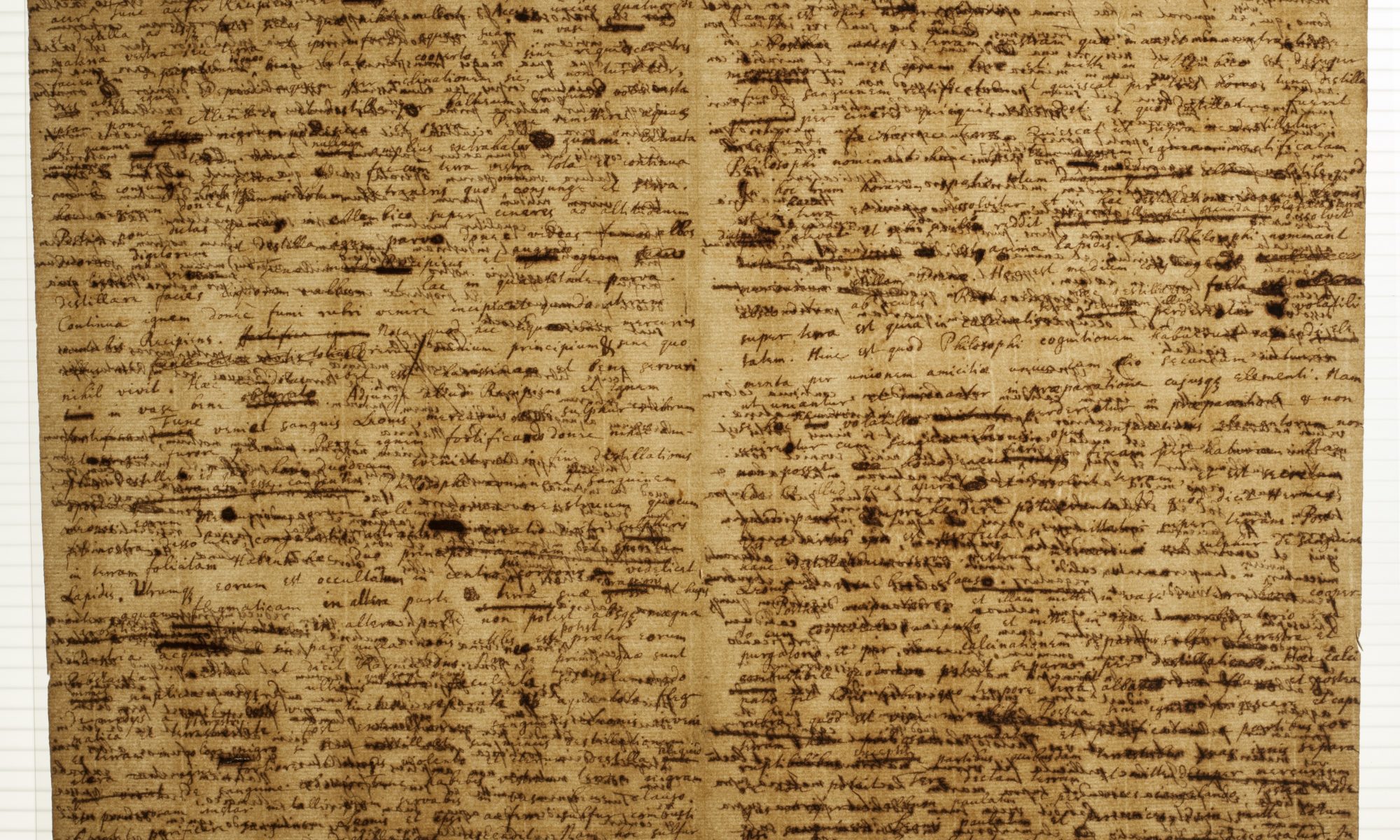

The paper of the manuscript is currently very brittle and has significantly fragile edges. Encapsulating it in mylar was an almost automatic solution to ensuring safe handling. However, the document is also significantly affected by the iron gall ink media, which is accelerating the breakdown of the paper substrate locally where the ink is applied, but also in the paper sheet writ large. We decided to leave the objects only partially encapsulated on two sides since we did not want to create a closed micro-environment that might act as a catalyst for the degradation reactions that are already happening inside the paper sheet.

Also, whereas a drop spine box can be an ideal structure for an object like a book that has significant depth to it, the manuscript is only 3 bifolia. So, creating a box that looked and functioned like a drop spine box but accommodated the minimal depth of the manuscript immediately required some creative problems solving. I explored the possibility of making something closer to a portfolio with an inner four-flap enclosure, but was dissatisfied with a portfolio’s ability to be self-closing or self-contained–there would have had to be an edge tie or some other means of securing it closed. From both a security as well as a handling point of view, the drop spine box offered an easy option for a protective enclosure that didn’t require additional ties, velcro, clasps, etc.

Eventually, I decided on using a material called volara, which is a closed-cell flexible foam, for making a kind of in-set pillow on the inside front cover that could gently compress and secure the document in the lower tray of the box. This is important because it keeps the document from moving or rattling around too much when being moved from place to place, but also eliminates the need for additional layers of enclosures which might involve extra handling, which from a user perspective, is not optimal.

What are some challenges you’ve encountered when working with the manuscript?

Oh boy. The thing about this type of enclosure is that a) there is not a lot of room for correction, so if something goes wrong during fabrication, it is much easier to start all over again than to try and fix a mistake, and b) the fit is everything for this enclosure, so if it is off by even a little, the box is just not going to work. I ended up making 4 different boxes, out of which only two were really usable and satisfactory. I knew this was a possibility going in, so I took a lot of time working through each iteration. Perhaps not the most efficient turnaround of a project I’ve had, but a good outcome was important, both for the safety of the object and for the what the box itself signifies. If you pull out a prized collection object and bring it to show a donor and the box is obviously messy or ill-fitting, it implicitly communicates what you feel about your collection. We didn’t want to communicate anything other than the utmost care and respect for the object, in this case, so belaboring the point was well worth it, in my mind.

Additionally, any time you are figuring out a novel solution to a problem you have never tackled before, there is always a grace period of experimentation in figuring out how to make your materials do what you want them to. For example, for the first box I made, I was using a light-weight wove marbled paper that pasted out well and was easy to wrap around the volara insert. However, after working with it, I found it was somewhat too thin and fragile to stand up to heavy use. I wanted something that was going to withstand opening and closing the box in perpetuity without showing significant age, damage or delamination, and I was just not confident that that would be the case. In later attempts, I switched to a high quality, robust, laid Italian marbled paper that was much less susceptible to the kind of damage that I observed previously. Of course, it turned out to have the opposite problems– it’s thickness and lack of absorption and malleability when glued up made it difficult to get it to do what I wanted. In the end, I found that wetting out the Italian paper with a fine mist of deionized water before applying adhesive gave me a little more working time and allowed the paper to be shaped around the insert in a way that worked for what I wanted.

Lastly–I was glad to finish the box and very much hope that it is to the complete satisfaction of the RBML staff, but I do not think this will be the last housing we make for the Newton manuscript. It will receive conservation treatment in the future, at which time it is totally possible that it will completely change dimension as a result of washing, mending, and full encapsulation. Rather than to try and anticipate what those changes in size might be and make a slightly oversized box for some future iteration of Newton, I decided it was more important to the document’s present handling and longevity to have a well-fitting box now. Even if that means having to make a brand new enclosure at a later time. If nothing else, I learned a lot this time around that I can apply to make an even better box in the future!