Justine S. Murison (English) is a 2023–2024 HRI Faculty Fellow. Murison’s manuscript, “American Obscenity: Realism in the Age of Comstock” examines the legal and cultural invention of “obscenity” in the United States.

Learn more about HRI’s Campus Fellowship Program, which supports a cohort of faculty and graduate students through a year of dedicated research and writing in a collaborative, interdisciplinary environment.

What is unique about your research on this topic?

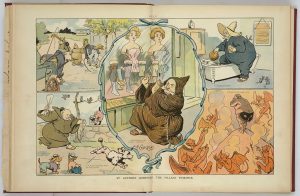

My new book project, American Obscenity: Realism in the Age of Comstock, examines the consolidation of a category of “obscenity” in United States federal law and its impact on the era’s literary culture. While pornography is a genre with a long history, the legal category of “obscenity” was effectively invented for the US after the Civil War. Established during a moral panic about the Free Love movement, the first federal legislation outlawing the distribution of “obscenity” was passed in 1873. Colloquially known as the Comstock Act after Anthony Comstock, a crusader in New York City for the “suppression of vice,” this federal legislation was the first to regulate the distribution through the US Postal Service of any material deemed lewd, corrupting, or sexually explicit. As I argue in this new book project, the 1873 law created the very category it was intended to regulate, and that genre included some strange bedfellows. It gathered together information about abortifacients and birth control with pornography and literature like Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

American Obscenity will be the first comprehensive literary history to theorize the influence of these new obscenity laws on the form and content of the realist novel, and thus I pose the era from 1870 to World War I as “the Age of Comstock.” Studies of nineteenth-century American literature—including my own—have sought to dislodge an older, prevalent theory that American realism was an invention that followed the Civil War. Even with several studies correcting this misperception, the field still largely names the era from 1880 to 1900 the “Age of Realism.” This book suggests instead that we call it the “Age of Comstock,” and it places the debates over the value and prominence of fictional realism within this wider context of attempts at censorship and the moral panics that prompted such attempts. My argument, though, is not that later nineteenth-century realism was actually unrealistic because of censorship; rather, I explain how realist writers invented a rich language to represent aspects of health and reproductive realities that were categorized as inappropriate, corrupting, or censurable. Equally important, the climate of censorship spurred a significant number of writers and artists to consolidate definitions of the “real” that would have sexual secrets at their core.

What drives your interest in this research?

American Obscenity extends the research I began in my last book, Faith in Exposure: Privacy and Secularism in the Nineteenth-Century United States (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2023). The final chapter of that book examined the exposure of Henry Ward Beecher’s extramarital affair by Free Love and women’s rights advocate Victoria Woodhull. The ensuing scandal led to the Beecher-Tilton trial for “criminal conversation” (a civil suit brought by a husband to collect damages in the case of adultery) and to Woodhull’s arrest in 1873 for the distribution of obscenity (and subsequent release, as her newspaper was protected under the First Amendment). Comstock, who led the crusade against Woodhull, was outraged at her release and campaigned in Washington for a federal obscenity law, which culminated in the 1873 act.

What became immediately apparent to me in that research was twofold: first, there is a need to theorize, from the perspective of genre theory and literary history, the influence of these new obscenity laws on literary history; and, second, the importance of understanding reproductive information as having once been legally and culturally categorized as obscene, and the lasting impacts of that for reproductive rights from the late nineteenth century to our post-Roe era.

Thus, the other thing that drives my research is its connection to our contemporary cultural, political, and legal environment of moral panics and debates over what should be available to read and by whom. With that in mind, I plan that the epilogue of the book will turn to our own era, following the decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022) that overturned Roe v. Wade (1973) to consider how the various state abortion laws (and potentially a federal law) operate not only on the level of what people seeking reproductive health can do, but in regulating what could be said or sent and to whom, and the surprising resurgence of the Comstock law (which is still technically on the books!) in these fights.

How has the fellowship seminar impacted the way you approach your research?

The fellowship seminar has impacted my writing and research in innumerable ways. This is my third book and I just started researching it several months before the seminar began. I therefore wrote my first chapter draft with the HRI seminar audience in mind. It helped me to loosen up my prose style and remember the importance of explaining historical or literary references or theoretical terms that might not translate out of my field. Doing so always makes for better scholarship, so I feel as if I am beginning ahead of where I usually am as I start a new research project. Our seminars this year have been both intellectually stimulating and supportive, which has made for a perfect environment for trying out new work. And reading other fellows’ research spurs me on to keep working on and writing my own. What an invaluable experience!