Eric Calderwood (Comparative and World Literature) held a 2023 HRI Summer Faculty Fellowship, during which he conducted fieldwork in Morocco and Spain for a new book project on the aesthetics and politics of multilingual art forms.

Learn more about HRI’s Summer Faculty Fellowships, which provide an infusion of resources designed to jumpstart or fuel an ongoing research project, undertake course development, or pursue a professional training opportunity over the summer months.

What is unique about your research on this topic?

My current project, tentatively titled “Babel’s Bounty,” explores the aesthetics and politics of multilingual art forms in the Mediterranean region. Something distinctive about my approach is that I am attempting to study the phenomenon of multilingual artistry in the “longue durée,” from the medieval period to the present. In other words, I am trying to place recent forms of multilingualism, like code-switching in contemporary North African hip hop, alongside much older forms of multilingualism, like the muwashshaḥ, a medieval song-form from al-Andalus that combined verses in classical Arabic with a final coda in colloquial Arabic, Romance, or a mixture of Arabic and Romance. By placing contemporary multilingual practices alongside much older practices, I’m hoping to bridge two of my main areas of research: medieval Iberian studies and postcolonial cultural studies. I’m also aiming to show how multilingual practices have allowed artists from diverse backgrounds and historical periods to position themselves within and across different categories of identity, such as race, religion, nationality, gender, and class.

What drives your interest in this research?

The questions that drive this research project are: How do multilingual arts function, how do they produce beauty or pleasure, and what social and political work do they perform? In other words, I’m trying to figure out what multilingualism does for the artists who produce it or for the audiences who engage with it. I’m also trying to figure out why some forms of multilingualism register as an unintelligible cacophony of language, whereas other forms of multilingualism make people smile or laugh, teach people to use language in a new way, and even inspire people to challenge and undermine existing systems of powers. In other words, I’m asking: When is multilingualism “babble” (or Bable), and when, and why, can it open up revolutionary possibilities? As I pose this question, I’m mindful that one person’s “babble” could be another person’s linguistic revolution. Indeed, something that fascinates me about multilingual art forms is their differential quality—the way they land differently with different audiences. As I’ve worked on this project, I’ve landed on the premise that one way to “get” multilingualism is to understand that someone else might get it differently. For that reason, multilingual art forms not only tell us a lot about the artists that make them but also about the diverse and overlapping communities that they evoke and produce.

How did the summer fellowship support your work?

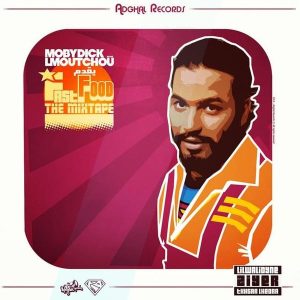

The HRI fellowship supported two months of fieldwork in Morocco and Spain, where I focused on one strand of my book project: my research on North African (and North African diasporic) hip hop. I began working on this topic in 2018 and 2019, but my initial work on it was interrupted by the COVID pandemic. During the pandemic, I relied on YouTube and social media to learn about North African hip hop from afar. But the HRI fellowship gave me an opportunity to engage with the North African hip hop scene in person by attending performances, meeting artists, and talking with hip hop enthusiasts in Morocco and Spain. For the bulk of my fieldwork, I was based in Tangier, Morocco, where I met local artists and attended performances. But I also established contact with cultural producers in Casablanca, who helped me to get oriented in the performing arts scene in Casablanca, the main hub for hip hop performance in Morocco. Next semester (Spring 2024), I will back in Morocco to resume my research with the support of a fellowship from the US Department of Education. My main goal will be to build on the working relationships that I began to develop over the summer. In particular, I am eager to deepen my engagement with artists and cultural producers in Casablanca. I am also working with the contacts that I made this summer to set up interviews with Khtek, Mobydick, and ElGrandeToto, three hip hop artists whose multilingual lyrics are of particular interest to me.

Although the main focus of my work over the summer was the research for my new project about multilingual arts, I also took advantage of my presence in Morocco to give some presentations about another strand of my research: my work on the history and legacies of al-Andalus (Muslim Iberia). To that end, I gave public presentations about my work (in Arabic, Spanish, and English) at several academic and cultural institutions in Morocco and Spain, including the Rabat International Book Fair (Salon International de l’Édition et du Livre), ʿAbd al-Malik al-Saʿdi University in Tetouan, the American Legation of Tangier, the Centro Cultural La Corrala in Madrid, and Casa Árabe in Cordoba. These presentations reflect my commitment to communicating my work to diverse audiences in Morocco and Spain, the two contexts that have been the centers of my research for the past seventeen years.

The HRI fellowship not only allowed me to launch new research and to establish new research collaborations, but it also gave me an opportunity to share my published research with new audiences. I’m extremely grateful to HRI for its support!