This week, from April 10th to April 17th, is the celebration of the Holy Week in the Christian world. In Latin America and the Caribbean, this religious festivity, as with most of the Catholic rituals celebrated in the region, must be read under the light of the historical process of colonization.

Latin America and the Caribbean is defined, in a great part, by Mestizaje. Mestizaje is a social process of encounters, beyond people’s skin color, which includes encounters and struggles involving and identity, beliefs, practices, power structures, and knowledges (See resources on mestizaje here). As a mestiza myself, I have been fascinated with noticing how religious practices and rituals contain and express very vividly the mixed nature of the region.

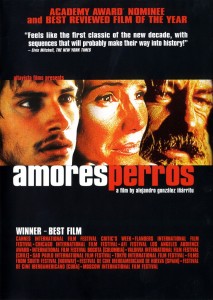

In fact, colonizing the spiritual beliefs of native communities was one of the most important strategies throughout the colonization of Latin America. Catholicism was carried by the colonizers as the religion of “civilization”, and only through evangelization would indigenous people overcome “savagery”. With this mindset, indigenous communities across a great portion of the continent were evangelized though a process called “reduction”. This referred to progressively converting native peoples to Catholicism in places called “missions“, which gathered the native communities for evangelization, agricultural production, crafts and construction. Evangelization took place through preaching the bible, instruction, and also through coercion. Natives would be forbidden to speak in their languages and their temples would be destroyed, among other practices of colonization. These missions were conducted mainly by Franciscan and Jesuit religious communities, and were particularly strong in the Andes (Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, northern Chile and Argentina), Paraguay and northern Brazil. Similar missions were also established in Central and North America, up to today’s Arizona, New Mexico and Texas (More information here). These missions grew almost like towns, and developed as agricultural and economic centers.

Left, Jesuit Missions in colonial Argentina (Image:Argentina Historica). Right, ruins of Jesuit Guaraní missions in Paraguay (Image: World Monuments Fund).

These practices extended from the early colonial times in the 1500s until the mid 1700s. The Jesuits were expelled from the Spanish empire around 1768. However, in some regions, similar practices of evangelization survived until the early 1800s (Read about the Jesuits in Latin America here. Additional resources at the library here).

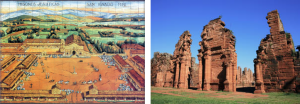

As is the case with other cultures that have gone through colonization, mixed beliefs and practices that blend elements from native and colonial traditions emerged in Latin America. At a religious level, rituals vividly reveal this process of mestizaje. Academic interpretations on how and why this mixture of beliefs took place, and of how this process dialogues with particular characteristics of each community, are too varied and extended to discuss here (See some resources here). The fact is that religious traditions become adapted to the cultures where they were installed. As an act of survival and, perhaps, resistance, native communities in Latin America appropriated these rituals and maintained elements from their own tradition despite colonization. Examples of this are the celebration of the Virgin of Candelaria. This Virgin is considered the patron saint of several towns across Latin America. In Paucartambo (in Cuzco, Peru), the Virgin of Candelaria is also known as “Mamacha Candelaria“, a term and a celebration which draws from native Andean religiosity.

Celebration of Mamacha Candelaria in Paucartambo, Peru. Image: Still from documentary “Festividad Virgen del Carmen de Paucartambo” by Folclore Peruano

Through a history of colonization, appropriation and syncretism, religiosity in Latin America has historically been experienced with passion and intensity. Therefore, the celebration of the Holy Week is a major celebration across the region.

Unlike the egg hunting celebration of the United States, the holy week of the Catholic tradition is heavily charged with a spirit of penitence and renewal. This is tied to both the Roman prosecution of Jesus, and the betrayal which lead to Jesus’ torture and crucifixion. The basic structure of holy week celebration in catholic countries which were Spanish colonies usually involves processions showing Jesus and Mary’s suffering: Starting on Palm Sunday with his entry to the city of Jerusalem where he was received as the son of God; through to Holy Friday, the passion, where he is crucified; and finally ending on Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday. Holy Friday, or Good Friday, is when the largest amount of processions take place, representing several stations from Jesus’ apprehension to his crucifixion. These biblical episodes are recreated as processions, each with vivid displays of statues and enacted representations, such as Christ’s imprisonment and execution, and the celebration of his resurrection. This is called Viacrucis.

Left, Viacrucis in Popayan, Colombia (image: Blog Semana Santa de Popayán). Right, Viacrucis at the lake Cocibolca, Nicaragua. Image: Fotoblog, “Hoy” Newspaper

Huge statues of saints are carried in procession, usually by men paying promises to them, and taken from churches into the streets, followed by believers. While maintaining these basic patterns , there are a great spectrum of variations of the kinds of displays and additional rites that have evolved in different communities.

The ritual celebrations of the Viacrucis in Popayan, Colombia, for example, are a very classic representation of the processions that take place in Spain, the country where the tradition first originated. The Judios de Masatete in Nicaragua and the Borrados in Nayarit, Mexico, on the other hand, demonstrate how the incorporation of native traditions and local culture can result in a very different representation of the same celebration. Another example is the lake Cocibolca in Nicaragua, where the procession is adapted to water with canoes.

These are just a few examples of the wide diversity of religious syncretism and celebrations that take place in Latin America which are strongly expressed during the period known as Holy Week. Countries like Mexico and Guatemala also present a rich variety of cultural expressions through Catholic rituals; while in Brazil and the Caribbean the Spanish and indigenous traditions blend together amidst a strong African influence.

If you are interested about these processes of mestizaje in Latin America and its manifestation on spiritual practices, we invite you to consult books as “South and Meso-American native spirituality: from the cult of the feathered serpent to the theology of liberation“. If you are fluent in Spanish you can also take a look at “Religiones y culturas : perspectivas latinoamericanas“. The library holds a large collection on Latin American cultures and religious traditions, as well as on Catholicism in that region. In addition, we invite you to visit out International and Area Studies Library, and bring your questions to our Librarian on Latin America and the Caribbean, Dr. Antonio Sotomayor.

![Photo credit: Lee Byoung-ok ; [translator Cho Yoon-jung]. "Korean folk dance", Seoul, Korea : Korea Foundation, c2008](http://publish.illinois.edu/iaslibrary/files/2015/10/korean-dance-223x300.jpg)