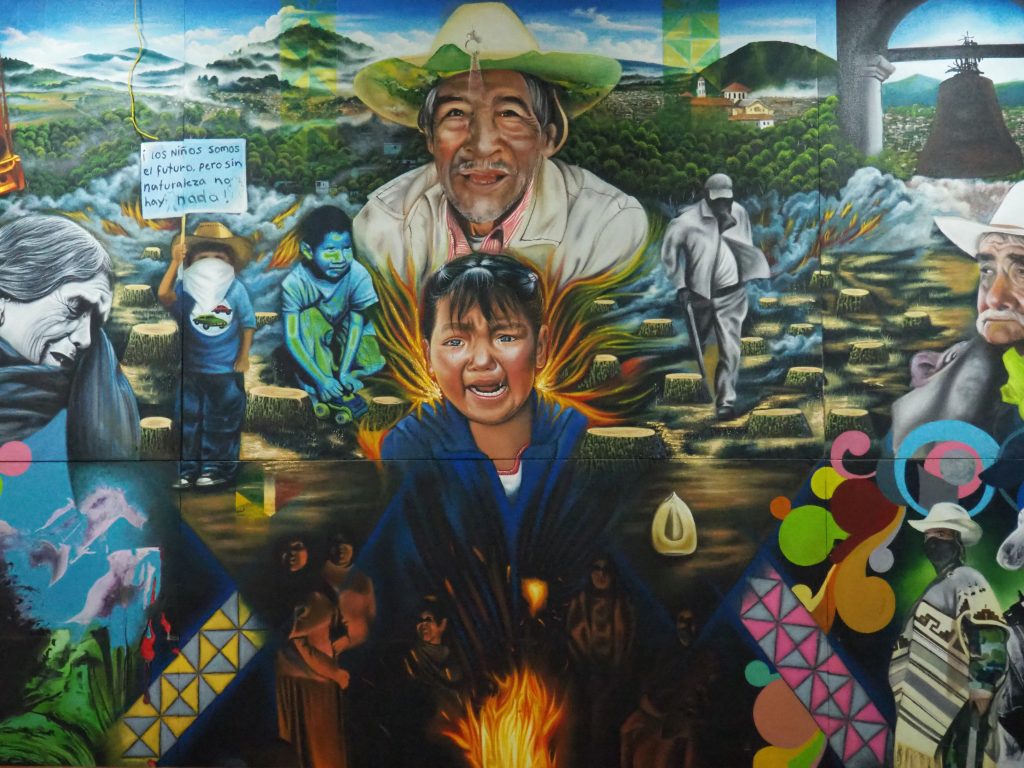

Yuridia Ramírez (History) is a 2022–2023 HRI Campus Faculty Fellow. Ramírez’s project, “Indigeneity on the Move: Transborder Politics from Michoacán to North Carolina,” traces the movement of P’urhépecha migrants from Cherán, Michoacán, México, to and from North Carolina during the late twentieth century.

Learn more about HRI’s Campus Fellowship Program, which supports a cohort of faculty and graduate students through a year of dedicated research and writing in a collaborative, interdisciplinary environment.

What is unique about your research on this topic?

My book, Indigeneity on the Move: Transborder Politics from Michoacán to North Carolina, is the first study of Indigenous Mexican migration to the U.S. South. By tracing the movement of Indigenous P’urhépecha migrants from Cherán, Michoacán, México, to and from North Carolina during the late twentieth century, my book historicizes both sides of the transborder circuit and contextualizes the racial and spatial logics of each with regard to the transformation of Indigeneity.

Scholars of Indigenous migration from Latin America to the United States have largely overlooked how Indigeneity functions as a contingent identity formation. I examine Indigeneity as a formation that is at times racialized, tracing how it changes over time, is repeatedly reconstituted, and is always contingent on time and place. I trace how P’urhépechas’ sense of Indigeneity also transforms in the diaspora for both migrants and those who stay behind.

“I have had to be creative with my archival sources to trace the history of migration from Cherán, Michoacán, to North Carolina. I am using materials from multiple archives in Mexico in ways that nobody else has done before.”

— Yuridia Ramírez

For example, I use Mexico’s agrarian administrative archives to trace land disputes between Cheranis and state and international forces that led to Cheranis’ migration. And, unlike historians of Mexican Indigeneity, I employ the records of the Mexican Indigenous Institute to trace one community’s history of migration.

What drives your interest in this research?

My academic work is principally driven by my own history of migration. My mother was pregnant with me when she crossed the border. Because I was born in the United States, I realized at a young age how my position of privilege differentiated me from family members and friends whose lives in the U.S. were constantly vulnerable. That injustice led me to work in immigrant rights activism during my undergraduate career, and I continued this work as a graduate student at Duke University.

I first met the Cherani community in 2011 when I was volunteering at a community organization in Durham, NC. My engagement with the Cherani community has taught me more about community organizing than I ever learned in formal trainings. I came to understand Cherán as the achievement of the beloved community.

My work is a community-engaged project that exists only because of the generosity and courage of my interlocutors. Throughout the years of my dissertation work and now book project, I have spent countless hours surrounded by Cherani migrants and their families, attending their celebrations, birthday parties, and weddings. I am the godmother of two children of Cherani migrants and have fictive kinship relationships with many others. I feel as responsible for the way I tell the stories in my book as if I were writing my own.

How has the fellowship seminar impacted the way you approach your research?

My colleagues’ expertise in various disciplines has pushed me to rethink the stakes and interventions of my work, drawing out important theoretical and methodological interventions I previously had downplayed. They approached my work with generosity and sincere engagement, and it has been a joy to share space with them.