The end of the semester is a stressful time with finals and preparing for the summer. During this time it is especially important to take care of your mental health and take some time for yourself. Here are some ways to relax using equipment from Scholarly Commons:

- Check out a Tranquility Kit to help with mental health during the stress of finals. This kit includes a Happy Light, headphones, exercise bands and an exercise guide, stress ball, and fidget toys. One of these kits is also available in the Orange Room on the first floor of the library.

- Read a book on an Amazon Kindle. The Kindles have 4GB memory storage which is enough storage for thousands of books.

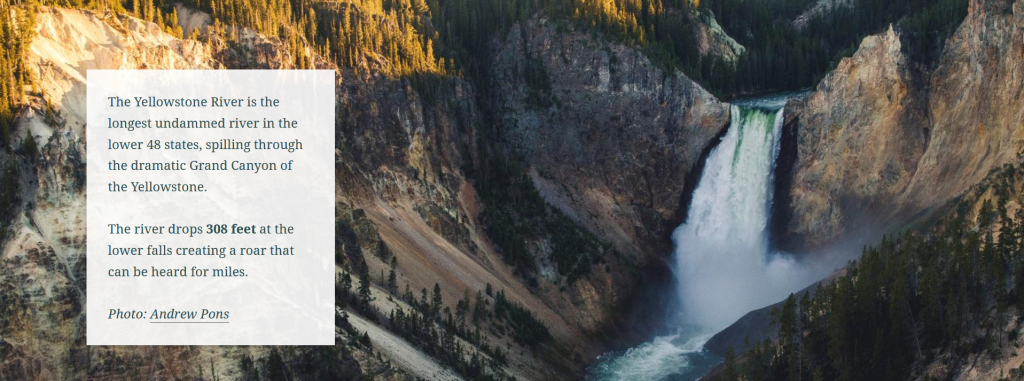

- Now that the weather is getting nice you can check out a camera and take a walk outside. Take pictures or videos of the campus or all the geese outside.

- Check out a projector and projector screen and watch a movie with friends.

- Try out our new Digital Drawing Kits with downloaded programs including Procreate, Sketchbook, Adobe Illustrator, Adult Coloring Book and Assembly.

- Check out Bluetooth speakers and headphones so that you can blast some music and have a dance party.

- Check out one of the sensory toys from the Orange Room while you study. Sensory toys available include a water wiggler, wacky tracks, and twisty tangles. Loanable technology from the Orange Room is available for two-hour check outs.

Technology from Scholarly Commons is available for loans of up to 10 days. You can book in advance on the Scholarly Commons website or make a booking at the Tech Desk in room 306. To pick up equipment, make sure to bring a valid i-card.

Good luck with finals! We’ll see you again next year!