This is the beginning of a new series where we introduce you to the various topics that we cover in the Scholarly Commons. Maybe you’re new to the field or you’re just to the point where you’re just too afraid to ask… Fear not! We are here to take it back to the basics!

What is digital scholarship, anyways?

Digital scholarship is an all-encompassing term and it can be used very broadly. Digital scholarship refers to the use of digital tools, methods, evidence, or any other digital materials to complete a scholarly project. So, if you are using digital means to construct, analyze, or present your research, you’re doing digital scholarship!

It seems really basic to say that digital scholarship is any project that uses digital means because nowadays, isn’t that every project? Yes and No. We use the term digital quite liberally…If you used Microsoft Word to just write your essay about a lab you did during class – that is not digital scholarship however if you used specialized software to analyze the results from a survey you used to gather data then you wrote about it in an essay that you then typed in Microsoft Word, then that is digital scholarship! If you then wanted to get this essay published and hosted in an online repository so that other researchers can find your essay, then that is digital scholarship too!

Many higher education institutions have digital scholarship centers at their campus that focus on providing specialized support for these types of projects. The Scholarly Commons is a digital scholarship space in the University Main Library! Digital scholarship centers are often pushing for new and innovative means of discovery. They have access to specialized software and hardware and provide a space for collaboration and consultations with subject experts that can help you achieve your project goals.

At the Scholarly Commons, we support a wide array of topics that support digital and data-driven scholarship that this series will cover in the future. We have established partners throughout the library and across the wider University campus to support students, staff, and faculty in their digital scholarship endeavors.

Here is a list of the digital scholarship service points we support:

- Copyright

- Data Discovery

- Data Management

- Data Purchase Program

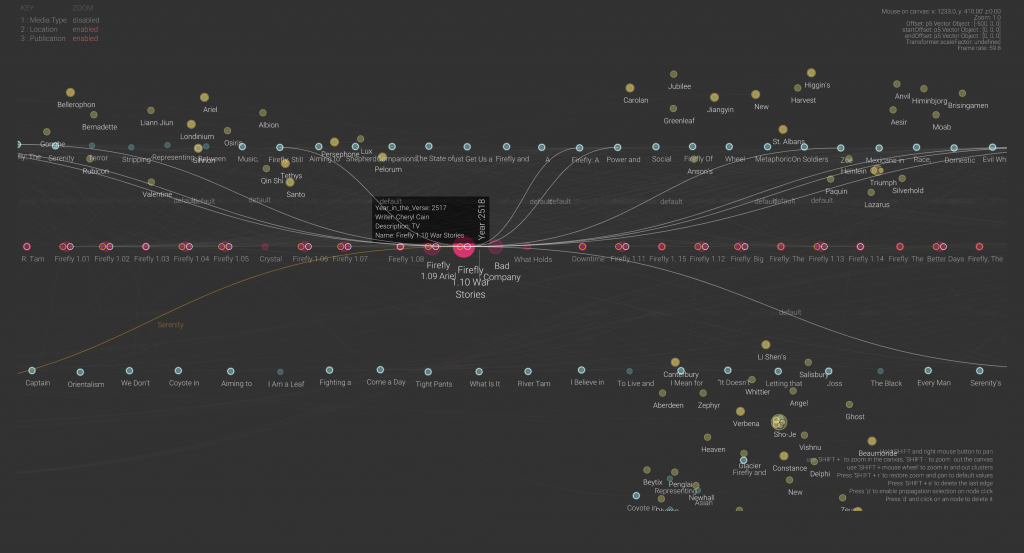

- Data Visualization

- Database Consulting

- Digital Humanities

- Digitization

- Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

- Illinois Experts and Research Profiles

- Illinois REDCap Consults

- Publishing and Open Access Services

- Repository Services

- Research Computing Consults

- Statistical Consults

- Undergraduate Research

- Usability Testing

You can find a list of all the software the Scholarly Commons has to support digital scholarship here and a list of the Scholarly Commons hardware here. If you’re interested in learning more about the foundations of digital scholarship follow along to our Introductions series as we got back to the basics.

As always, if you’re interested in learning more about digital scholarship and how to support your own projects you can fill out a consultation request form, attend a Savvy Researcher Workshop, Live Chat with us on Ask a Librarian, or send us an email. We are always happy to help!