Are blood parasites found in resident and migratory birds in Illinois?

By Kelsey Martin, Nelda A. Rivera, Nohra E. Mateus-Pinilla [PDF]

Parasitic infections in birds are a significant threat to the health and conservation of avian species. Avian haemosporidian parasites are blood parasites found globally in birds. These blood parasites have a non-specific, broad range of avian hosts and are transmitted by biting vectors that participate in the parasites’ life cycle (Figure 1). For example, Leucocytozoon parasites are transmitted to birds by black flies, and mosquitoes transmit Plasmodium parasites (responsible for malaria) and Haemoproteus parasites. Similar to human malaria, infected birds may develop malaria-like disease,

anorexia (low body weight), hemolytic anemia (destruction of red blood cells), lethargy, and depression, among many other clinical signs. All these clinical signs may result in behavioral changes and death.

Avian blood parasites will infect any bird that is a suitable host. In fact, haemosporidian parasites have been found on birds’ blood smears from every continent except Antarctica (Figure 2; Smith et al., 2016). Reports of haemosporidians in European birds of prey and owls (Krone et al., 2008), endangered South African penguins (Snyman et al., 2020), endangered North American quails (Bertram et al., 2017,) and whooping cranes (Pacheco et al., 2011) emphasize the importance of epidemiological surveys to evaluate blood parasites that could be affecting bird populations around the world (Figure 2). Surveying haemosporidian parasites are essential to determine emerging or reemerging parasite infections, geographic distribution and expansion of the blood parasites, the bird species affected by the parasites, and disease outbreaks caused by different parasite species.

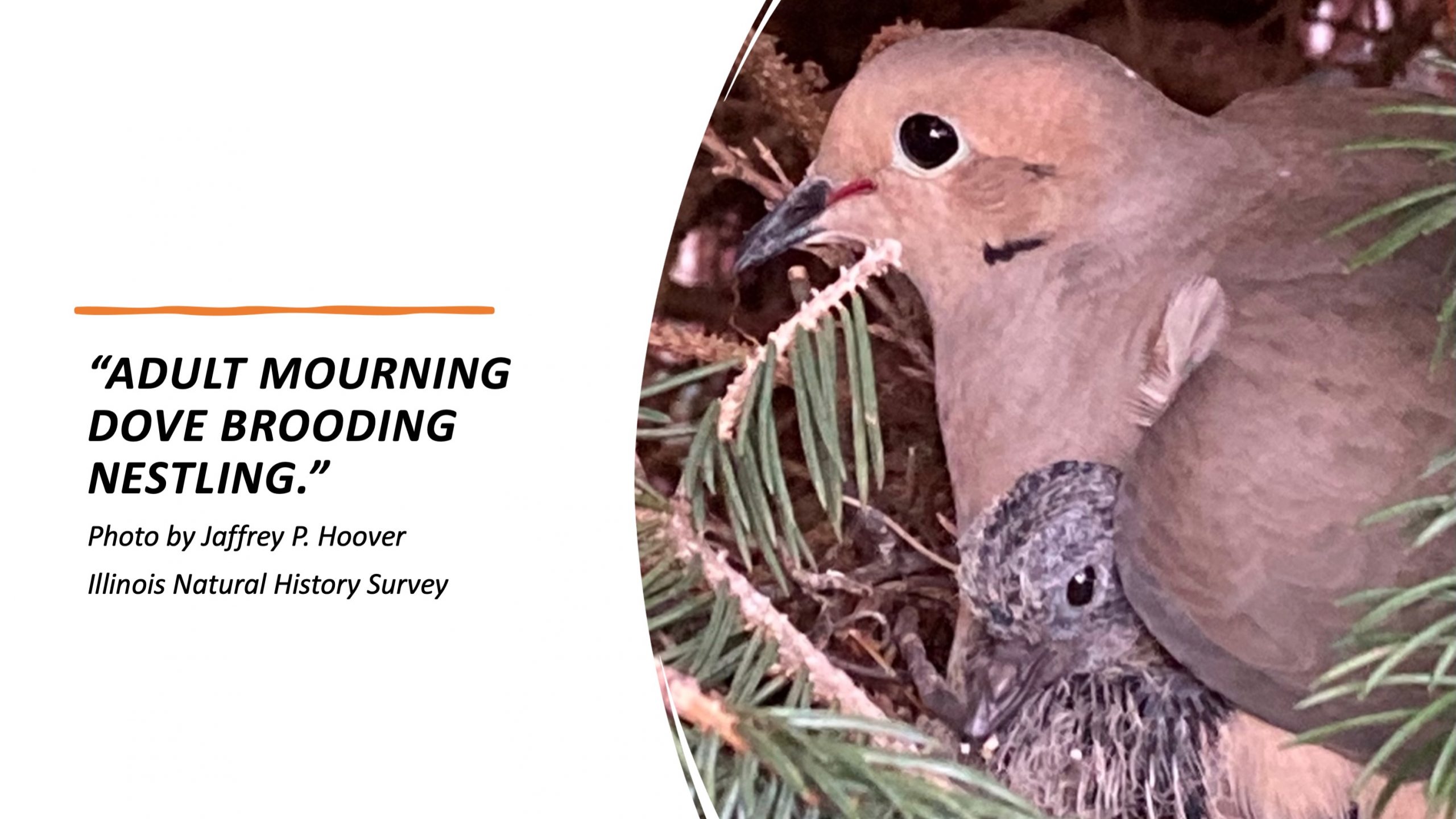

In Illinois, a study conducted by Annetti et al. (2017) surveyed haemosporidian parasites in four different bird species. For the study, Annetti and collaborators collected blood samples from mourning doves, wood ducks, Canada geese, and wild turkeys, which were then evaluated for the presence of parasites at the Wildlife Veterinary Epidemiology Laboratory of the Illinois Natural History Survey at the University of Illinois. Three of the bird species (mourning doves, wood ducks, and Canada geese) could migrate, meaning they could be infected in another state, and they could have brought the parasite to Illinois from the prior migrating location. Wild turkeys were the only non-migratory species surveyed, which made the study’s findings specific to Illinois.

The study found three genera of haemosporidian parasites: Haemoproteus, Plasmodium, and Leucocytozoon (Annetti et al., 2017). The most abundant genus, Haemoproteus, was found in all four avian hosts. Wild turkeys, the only Illinois resident birds in the study, were also the only species infected with all three haemosporidians, which means that they were infected in Illinois by different vectors carrying each different parasite.

“Vectors that participate in the life cycle of haemosporidian parasites are blood-sucking insects such as biting midges or black flies.”

Figure 3. Common loons attack by black flies while sitting at their nest.

Mourning doves and wild turkeys overall showed a greater prevalence of infection than the waterfowl species (Canada geese and wood ducks), but wild turkeys were the only species infected with all three haemoparasites species, while mourning doves were only infected with Haemoproteus. The difference in infection rates between mourning doves and wild turkeys tells us that migratory doves, at the time of the study, were not reservoirs for the other two parasites (Leucocytozoon and Plasmodium). However, due to the migratory behavior of mourning doves, infection of the other two parasites can occur while migrating through Illinois, which they then spread to other states through their migration.

The team also determined that waterfowl species (Canada geese and wood ducks) had significantly fewer infection rates than mourning doves and wild turkeys. The differences in infection rates between waterfowl and other bird species may be due to factors that affect waterfowl species, such as climate change and food availability, that impact migratory patterns. Indeed, migration plays an important role in the prevalence of Haemoproteus, Plasmodium, and Leucocytozoon parasites. In a study of blood parasites in Japanese birds done by Yoshimura et al. (2014), researchers found that both resident birds and migratory birds are susceptible to infection by haemoparasites; it is possible that migratory birds can serve as reservoirs and carriers of parasites. Similarly, Annetti et al. (2017) found waterfowl species had a lower prevalence of infection, which could be explained, for example, by the change in migration patterns of species like resident Canada geese. Because resident Canada geese no longer migrate as far north as they used to, they experience less interaction with parasitic vectors, which may decrease the prevalence of infection in waterfowl species.

“Further studies should focus on looking at the health parameters in birds, run vector surveys, and evaluate weather and season variability.”

Because haemosporidian infection can cause serious health implications for birds — from severe parasitic infection and death to subclinical disease affecting reproduction and long-term fitness —, monitoring haemoparasites is a critical component to the conservation and health of avian species. Further studies should focus on looking at the health parameters in birds, run vector surveys, and evaluate weather and season variability. Additionally, wild turkeys should be given special consideration and monitoring due to the presence of several haemoparasite species. Haemosporidian parasites do not seem to discriminate between species, so it is essential to monitor various avian species across time to detect early signs of disease outbreaks.

References:

Annetti, Kendall L., et al. “Survey of Haemosporidian Parasites in Resident and Migrant Game Birds of Illinois.” Journal of Fish and Wildlife Management, vol. 8, no. 2, 2017, pp. 661–68, doi:10.3996/082016-JFWM-059.

Bertram, Miranda R., et al. “Haemosporida Prevalence and Diversity Are Similar in Endangered Wild Whooping Cranes (Grus Americana) and Sympatric Sandhill Cranes (Grus Canadensis).” Parasitology, vol. 144, no. 5, 2017, pp. 629–40, doi:10.1017/S0031182016002298.

Krone, Author O., et al. Haemosporidian Blood Parasites in European Birds of Prey and Owls Published by : Allen Press on Behalf of The American Society of Parasitologists Stable URL : Https://Www.Jstor.Org/Stable/40059079 REFERENCES Linked References Are Available on JSTOR for Th. Vol. 94, no. 3, 2008, pp. 709–15.

Pacheco, M. Andreína, et al. “Haemosporidian Infection in Captive Masked Bobwhite Quail (Colinus Virginianus Ridgwayi), an Endangered Subspecies of the Northern Bobwhite Quail.” Veterinary Parasitology, vol. 182, no. 2–4, 2011, pp. 113–20, doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.06.006.

Smith, Matthew M., et al. “Haemosporidian Parasite Infections in Grouse and Ptarmigan: Prevalence and Genetic Diversity of Blood Parasites in Resident Alaskan Birds.” International Journal for Parasitology: Parasites and Wildlife, vol. 5, no. 3, Elsevier Ltd, 2016, pp. 229–39, doi:10.1016/j.ijppaw.2016.07.003.

Snyman, Albert, et al. “Determinants of External and Blood Parasite Load in African Penguins (Spheniscus Demersus) Admitted for Rehabilitation.” Parasitology, vol. 147, no. 5, 2020, pp. 577–83, doi:10.1017/S0031182020000141.

Yoshimura, Aya, et al. “Phylogenetic Comparison of Avian Haemosporidian Parasites from Resident and Migratory Birds in Northern Japan.” Journal of Wildlife Diseases, vol. 50, no. 2, 2014, pp. 235–42, doi:10.7589/2013-03-071.

Figure 1.

- The lifecycle of P.falciparum. Balazs Fazekas, University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 0SP. doi: 10.7244/cmj-1323558924

- Loon chick with a parent. Lake One of the Kawishiwi River, Ely, MN. Photo by Leellen Solter.

Figure 2.

- A mosquito bites the face of an apapane, Photo by Jack Jefferey. Available online https://www.fws.gov/pacificislands/articles.cfm?id=149489735

- Male and female haemoproteus columbae. Photo by PlasmodiumLady. Description: Male gametocyte in the upper left cell stains with more pink (Giemsa staining) than the female parasite in the lower left, which is more blue in color. Rock Pigeon red blood cells are nucleated, stained dark purple in this photograph. Also depicted is a thrombocyte, the avian equivalent of a platelet cell with clear/no staining around its nucleus. DNA stains more pink and protein stains more blue using Giemsa stain (hence, the male parasite, which will exflagellate upon uptake by a blood feeding Pseudolynchia canariensis louse fly vector) is more pink and the female “egg like” parasite contains more protein and is more blue. Photo taken using bright field light at 1000x total magnification (100x lens, oil immersion). Available online https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Male_and_female_haem_columbae.jpg)

Figure 3.

- Black fly “Note the flies on the unfeathered skin surrounding the loon’s eyes.” https://www.startribune.com/black-flies-biting-into-bird-nesting/266267681/

Figure 4.

- Discover Nature: Canada Goose Nesting. By Kyle Felling. KBIA. Available online https://www.kbia.org/arts-and-culture/2020-03-24/discover-nature-canada-goose-nesting

- Two ducklings in a hole in a tree. Picture courtesy of Wood Duck Society. Available online http://www.woodducksociety.com/qanda.htm

- Mourning dove on nest. Picture courtesy of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Available online https://www.flickr.com/photos/usfwsnortheast/48671134841

- Wild turkey nest. Picture courtesy of Jeffrey P. Hoover, Illinois Natural History Survey.

[PDF] Martin K.; Rivera, N.A.; Mateus-Pinilla, N.E. 2021. Hemosporidian parasites in Illinois: Are blood parasites found in resident and migratory birds in Illinois? ©Wildlife Veterinary Epidemiology Laboratory, Illinois Natural History Survey, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.