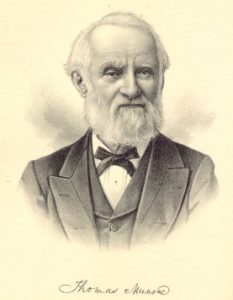

Thomas Munroe was a surgeon with the 119th Illinois Volunteer Infantry during the Civil War. Born on January 4, 1807 in Annapolis, Maryland, he went on to graduate from St. John’s College with honors and then attended the University of Maryland in Baltimore, graduating with a degree in medicine in 1829. After graduation, Munroe practiced medicine in Baltimore for a year before deciding to go West. In 1834 he moved to Illinois, first settling in Jacksonville. He was married on October 5, 1841, to Annis Hinman, and in 1843 they moved to Rushville where Munroe continued to practice medicine. When the Civil War began, Munroe enlisted and was commissioned Surgeon of the 119th Illinois Volunteer Infantry. After the war Munroe returned home where he continued his practice until shortly before his death on April 23, 1891.

Thomas Munroe was a surgeon with the 119th Illinois Volunteer Infantry during the Civil War. Born on January 4, 1807 in Annapolis, Maryland, he went on to graduate from St. John’s College with honors and then attended the University of Maryland in Baltimore, graduating with a degree in medicine in 1829. After graduation, Munroe practiced medicine in Baltimore for a year before deciding to go West. In 1834 he moved to Illinois, first settling in Jacksonville. He was married on October 5, 1841, to Annis Hinman, and in 1843 they moved to Rushville where Munroe continued to practice medicine. When the Civil War began, Munroe enlisted and was commissioned Surgeon of the 119th Illinois Volunteer Infantry. After the war Munroe returned home where he continued his practice until shortly before his death on April 23, 1891.

The Thomas Munroe Papers, 1832-1894 (MS 146) contain correspondence, records, and miscellaneous printed works collected by Munroe. Two of the letters in this collection were written to Munroe during the Civil War. The first, dated March 24, 1864, is from his son, Thomas Jr., who was attending school in Bloomington, Illinois. He wrote, “As you have been on a long and dreary march exposed to no little danger, I would have written sooner but I did not know wheather [sic] you would get it or not.”

Thomas Jr. went on to write about his success with his examination, saying “I passed a good examination being almost perfect in all my studies a thing which all do not accomplish.”

He closed the letter wishing for his father’s safe return: “I hope to see you home soon. then we will be a happy family. you do not know how anxious I was for your safety – watched the papers for news from Sherman every day. but thank God you are safe so far and I pray you will be permitted to reach home in safety.”

The second letter, dated January 25, 1865, is from first assistant surgeon Reuben Woods, discussing the living conditions and medical problems among soldiers in several regiments, including the 119th and 122nd Illinois Volunteer Infantry, the 21st Missouri Volunteer Infantry, and the 89th Indiana Volunteer Infantry.

Woods described setting up camp at Eastport and noted that while they had plenty of good water, lumber for shelter, and brick for chimneys, there was a food shortage. Woods wrote:

The only thing we need now is Rations and they are not to be had here at present. I am confident there is not ten pounds of Hard Tack in our Brigade nor as much bread of any kind. Officers and men are out. For two days, we have drawn Corn which the men make into hominy. I have not tasted bread for two days and have almost come to the conclusion that I like the Hominy best any how! Boats loaded with Comissary Stores have been expected every day for a week, and I think they will surely be here tomorrow.

Both the Union and Confederate armies had guidelines for appropriate rations for their troops, but the ability to maintain these standards depended on the troops’ location, the season of the year, and the period of the war. Food shortages, poor quality rations, and a lack of nutritional variety could cause digestive diseases and other ailments. Despite these limited rations, Woods went on to describe the overall health of the troops. Several of the lines in this letter are missing words due to a tear (the empty brackets indicate a missing portion of the letter). Woods wrote:

[The] health of the Regt is very good. One case of measles [ ] person of one of the old Roman family of Wilsons [whom] I presume you remember in Co. F. he is a brother to the [ ] who were here when you were with us, and is a recruit [for] us at Nashville. and took measles instantly. [He gets] along very well and I do not apprehend any trouble with him. We have a Brig Hosp. in which are quite a number of sick from the 21st Mo. & 89th Ind. and some few from the 122nd Ills. but none from this regt.

Disease was a very serious issue throughout the Civil War. Two-thirds of the soldiers who died during the war were killed by uncontrolled infectious diseases, such as measles. Measles was a highly contagious disease that spread through both the Union and Confederate armies, especially when soldiers had not previously been exposed to it. The Union Army had over 67,000 cases of measles, and more than 4,000 soldiers died of it. Measles was known as a disease that ran a certain course and could not be shortened, so doctors tried to alleviate the symptoms and provide patients with proper nourishment.

Woods finished off his letter by reporting, “My health is very good. much better than last spring and Summer. Dr. Byrns and all the boys around the hospital are well. Capt Curry has been quite sick but is now much better.”

You can read more about Civil War surgeons in the IHLC’s holdings here: https://bit.ly/2LSNiln and check out some of our other collections on surgeons throughout Illinois’s history here: https://bit.ly/2EykkDg

IHLC Resources

Schroeder-Lein, Glenna R. The Encyclopedia of Civil War Medicine. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, Inc., 2008. Call number: 973.77503 Sch764e.

Other Resources

Biographical Review of Cass, Schuyler and Brown Counties, Illinois: Containing Biographical Sketches of Pioneers and Leading Citizens. Chicago, IL: Biographical Review Publishing Company, 1892.

“Measles Plays a Role in the Civil War.” The History of Vaccines, The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. Retrieved December 17, 2019. https://www.historyofvaccines.org/content/measles-plays-role-civil-war.

Interesting family history! Thomas Monroe appears unrelated to Thomas Groom or the Groom family. From Groom’s FindaGrave page, he was born in Ohio.

Is this the same Thomas Groom who was a doctor during the Civil War

My Dad, Ora Murra Groom. (1906-1993) had a Grandfather (Thomas Groom) who was a Civil War doctor

Mye ( not sure about Dad’s.father was William Grant Groom. (Many people called him Billy). William had. many children.. His wife’s name was Rachel Susan Elisabeth. Groom ( They called her Rachael) Their children were Leona. Earl, Roe, Curtis, Ray, Edna,. Ora. Perry.( some called.him.Percy) and Osie ( not sure about the spelling) Osie died on the trip to Kansas in a covered wagon.