This work will be presented at the 184th Meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, May 2023, in Chicago, Illinois.

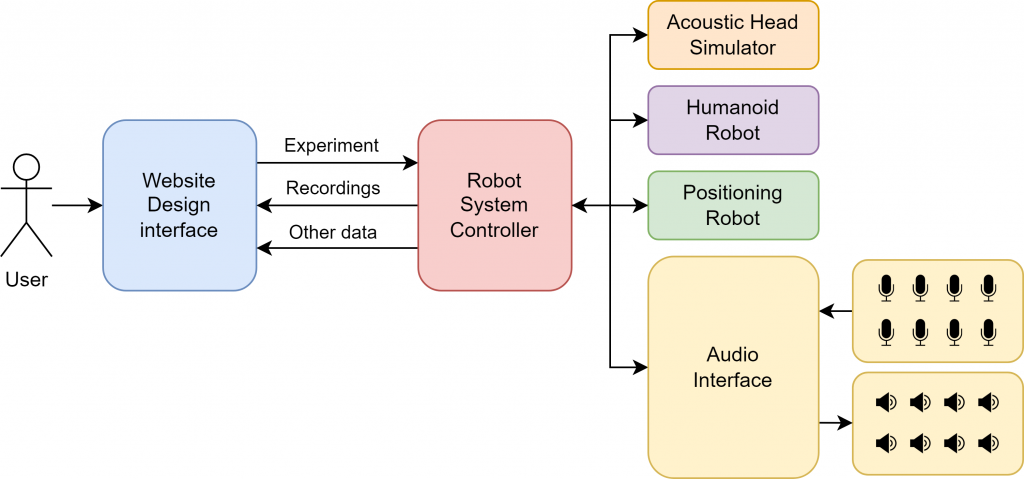

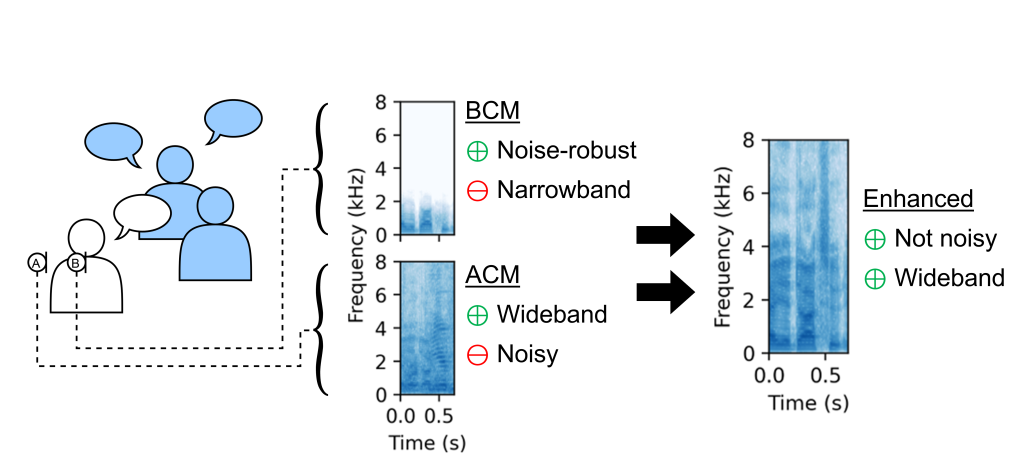

Conventional microphones can be referred to as air-conduction mics (ACMs), because they capture sound that propagates through the air. ACMs can record wideband audio, but will capture sounds from undesired sources in noisy scenarios.

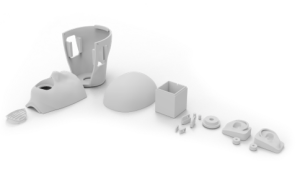

In contrast, bone-conduction mics (BCMs) are worn directly on a person to detect sounds propagating through the body. While this can isolate the wearer’s speech, it also severely degrades the quality. We can model this degradation as a low-pass filter.

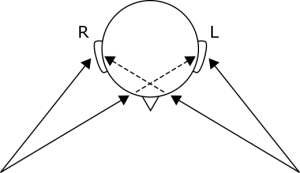

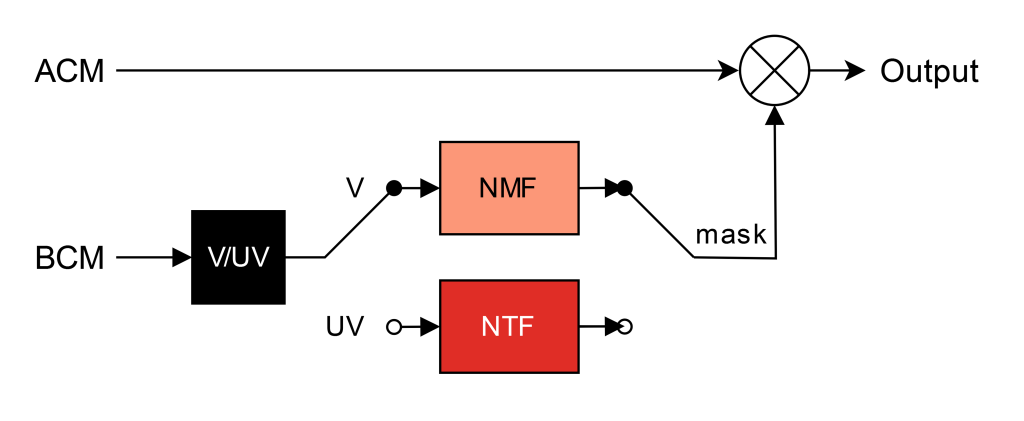

To enhance a target talker’s speech, we can use the BCM for a noise-robust speech estimate, and combine it with ACM audio by applying a ratio mask in the time-frequency domain

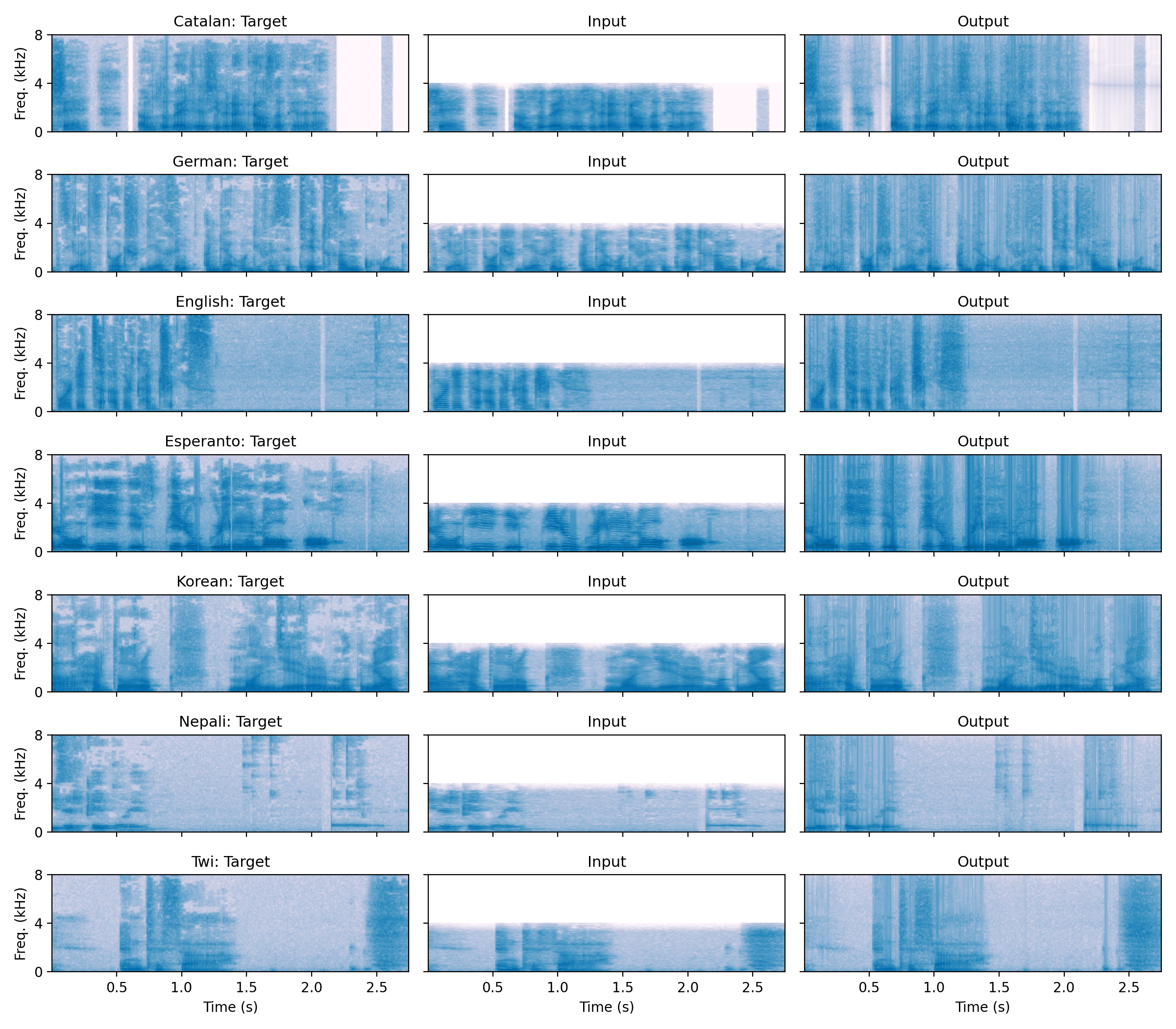

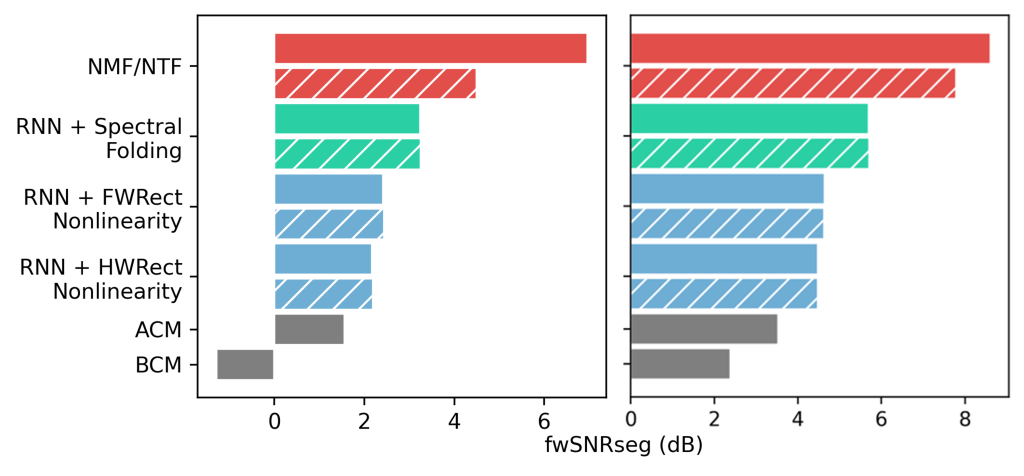

Factorization methods outperform parametric methods for BWE of female (left) and male (right) speech. The ensemble systems (solid) can significantly outperform baseline systems (striped)

However, the BCM only provides good estimates of the lower frequencies. Therefore, we need to estimate the missing upper frequencies. This task is called bandwidth extension (BWE), and can be solved in a variety of ways.

We found that ensemble factorization approaches can significantly outperform other low-compute BWE methods.

The ensemble factorization method uses two expert models for voiced and unvoiced speech segments

We provide listening examples of our proposed ensemble system. The audio data was generated from a simulated indoor, multi-talker scene.

| Female | Male | |

|---|---|---|

| BCM | ||

| ACM | ||

| Baseline | ||

| Proposed |