On the evening of April 14, 1865 John Wilkes Booth assassinated President Abraham Lincoln at Ford’s Theatre in Washington, D.C. Lincoln sustained a gunshot wound to the back of the head and was carried to a boardinghouse across the street where the surgeon general arrived to attend to him. Lincoln died the next morning on Saturday, April 15, 1865, at the age of 56. Several hours later Andrew Johnson was sworn in as the seventeenth President of the United States, and on April 18 the doors to the White House were opened for people to come through to view the coffin. On April 20, thousands more viewed Lincoln’s casket in the rotunda of the Capitol. While these events all happened relatively quickly, they were just the beginning of Lincoln’s funeral procession.

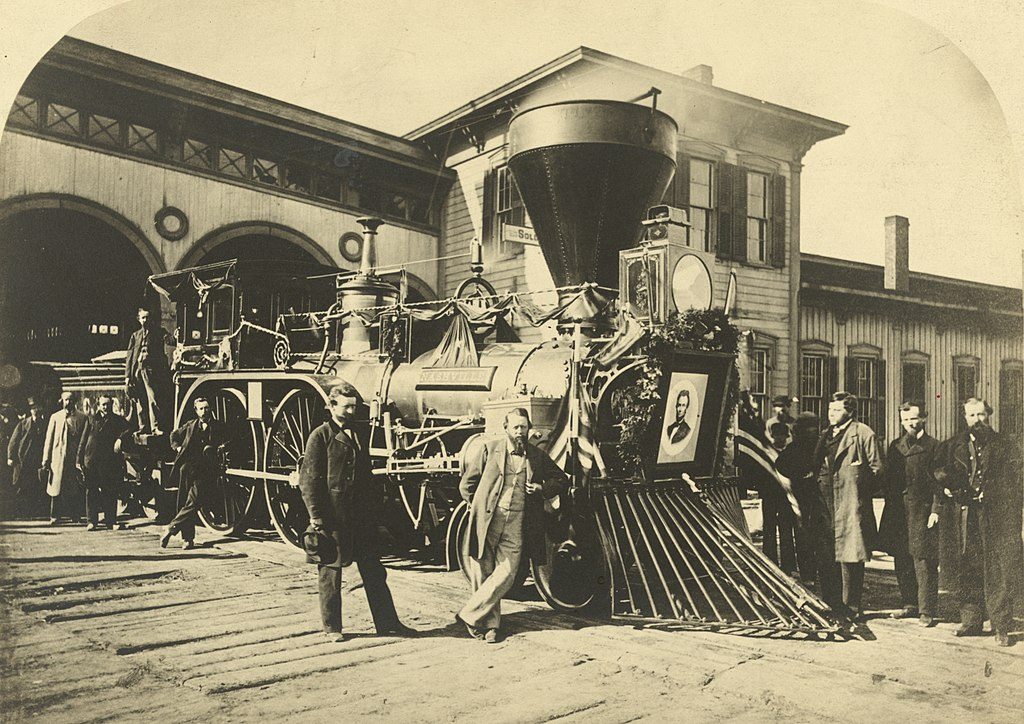

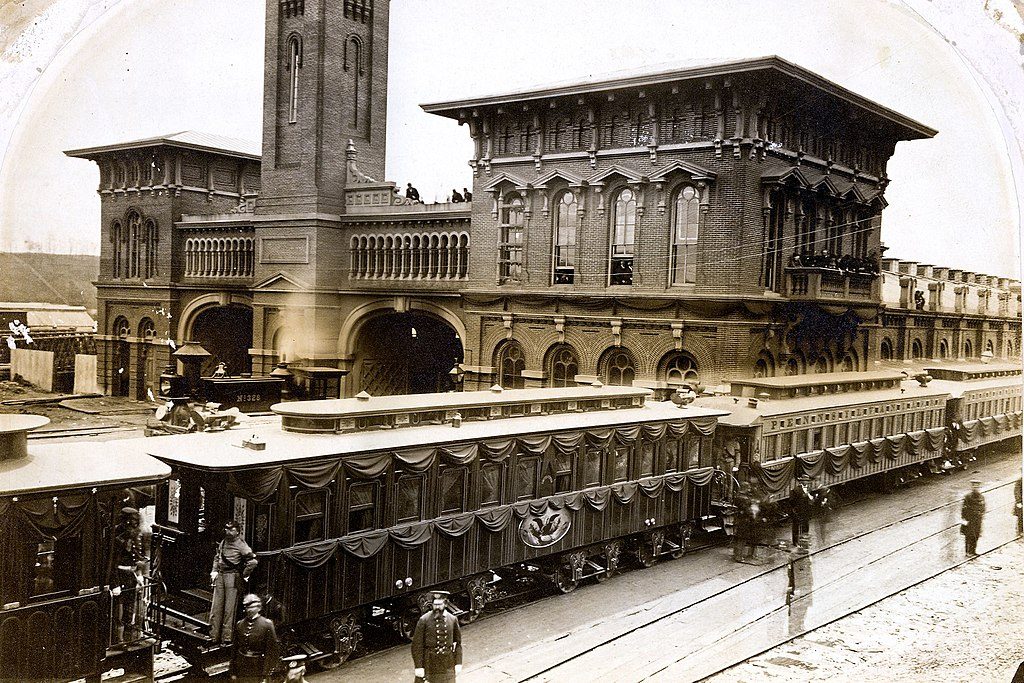

On April 21, 1865, a train carrying the coffin of President Lincoln left Washington, D.C., to travel to Springfield, Illinois, for the president’s burial there on May 4. The funeral train consisted of nine cars and carried 300 guests along with Lincoln’s casket. The train also carried the casket of Lincoln’s son, Willie Lincoln, who had died three years earlier. Mary Todd Lincoln had decided that he should also be buried in the family plot in Springfield.

The train, dubbed “The Lincoln Special,” traveled through 180 cities and seven states, and scheduled stops were published in newspapers so mourners could gather. In ten cities, Lincoln’s coffin was placed on a horse-drawn hearse and was carried to a public building where members of the public then filed through to see Lincoln lying in repose. Newspapers at the time reported that people would wait in line for over five hours just to pass by the coffin in some cities. As the funeral car traveled through the countryside, even more gathered along the train’s route to pay their respects as the train passed through. The train traveled 1,654 miles over the course of this journey to Springfield. Approximately one and a half million Americans viewed Lincoln’s body and more than seven million saw the train or a hearse in passing. Lincoln was finally buried at Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield, Illinois.

Abraham Lincoln was the first American president whose body was transported by a funeral train. In later years Presidents James A. Garfield, Ulysses S. Grant, William McKinley, Warren G. Harding, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and George H.W. Bush would all be transported to their final resting places by a ceremonial funeral train as well. At the time of Lincoln’s death, however, railroads were still in their early years and remained something of a novelty for many Americans. Throughout this period of mourning, the Lincoln funeral train introduced many Americans to a first-hand view of train travel. This monumental funeral procession even played a role in the evolution of train travel and tangentially contributed to a rise in luxury trains. George Pullman was an engineer and industrialist from Chicago, and in the 1850s he became interested in developing a comfortable railroad “sleeping car.” He was inspired with this idea after he had experienced an uncomfortable trip in upstate New York, and by 1863 he had developed two models – the Pioneer and the Springfield. The Springfield was named after Lincoln’s hometown. The railroad sleeping car was also known as the Pullman sleeper or “palace car.” Although Pullman’s sleeper cars achieved the comfort he desired, they were incredibly expensive. Few passengers were able to afford this type of travel, and railroad companies were unable to lease them with such a small pool of customers. This changed, though, after Lincoln’s death. The government decided to bring the Pioneer into service to form part of the funeral train. This luxurious Pullman car required renovation efforts at every station and bridge between Chicago and Springfield to accommodate the carriage’s width. The funeral train became front page news, and the Pullman sleeping car became a rapid success. Pullman’s Palace Car Company was officially incorporated in Illinois two years later in 1867.

Even years after the funeral procession had come to an end, the ties between Pullman and Lincoln continued. Abraham Lincoln’s eldest son, Robert Todd Lincoln, went on to act as general counsel at the Pullman Palace Car Company in Chicago in the early 1890s, and he then served as the acting president when George Pullman died in 1897. This role became permanent in 1901, and he continued to act as president until he resigned in 1911. Even then he remained actively involved as the chairman of the board until 1922. The Pullman Company thrived through the 1920s and, like many other railroad companies, began to decline in the 1950s. Pullman Company ended the operation of its sleeper cars in 1968.

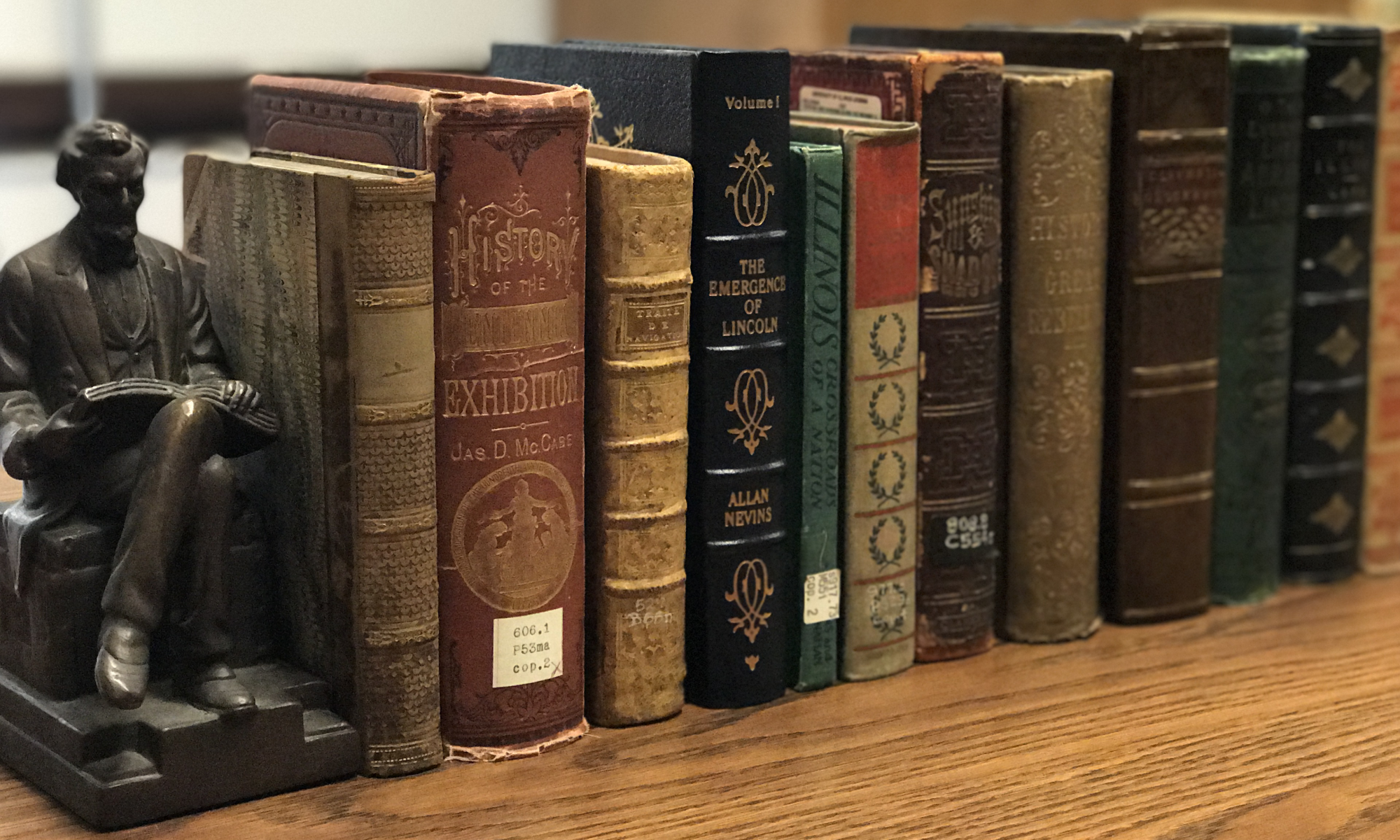

You can see a photograph of the Lincoln funeral train from Ralph G. Newman’s “In This Sad World of Ours, Sorrow Comes to All”: A Timetable for the Lincoln Funeral Train (Call number 973.7 L63D2N467I) and The Lonesome Train: A Musical Legend (Call number 973.7 L63H5R561L), a cantata by Earl Robinson and Millard Lampell, along with other items related to the history of the railroad in Illinois, in the IHLC’s exhibition, The Iron Horse of the Prairie State, on view now through October 2019.

IHLC Resources

Leavy, Michael. The Lincoln Funeral: An Illustrated History. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, LLC, 2015. Call number: 973.7L63D2 L489l.

Reed, Robert M. Lincoln’s Funeral Train. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2014. Call number:

973.7L63D2 R2518li.

Trostel, Scott D. The Lincoln Funeral Train: The Final Journey and National Funeral for Abraham Lincoln. Fletcher, OH: Cam-Tech Publishing, 2002. Call number: Q. 973.7 L63D2T755L.

Other Resources

“Abraham Lincoln’s Funeral Train.” HISTORY, October 27, 2009, https://www.history.com/topics/american-civil-war/president-lincolns-funeral-train

Maranzani, Barbara. “8 Things You May Not Know About Trains.” HISTORY, December 11, 2012, https://www.history.com/news/8-things-you-may-not-know-about-trains

“Robert Todd Lincoln Biography.” Biography.com, April 2, 2014, https://www.biography.com/political-figure/robert-todd-lincoln

Stamp, Jimmy. “Traveling in Style and Comfort: The Pullman Sleeping Car.” Smothsonian.com, December 11, 2013, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/traveling-style-and-comfort-pullman-sleeping-car-180949300/

Hi Ann, thanks for your question! Lincoln’s funeral train arrived at what was then called the Chicago & Alton Depot Station on Washington and 3rd streets in Springfield. Though the original station no longer exists, the current Springfield Station remains at the same spot. Please let us know if you have any additional questions.

What train station in Springfield, IL did Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train return to bring his body back to Springfield for his burial ?