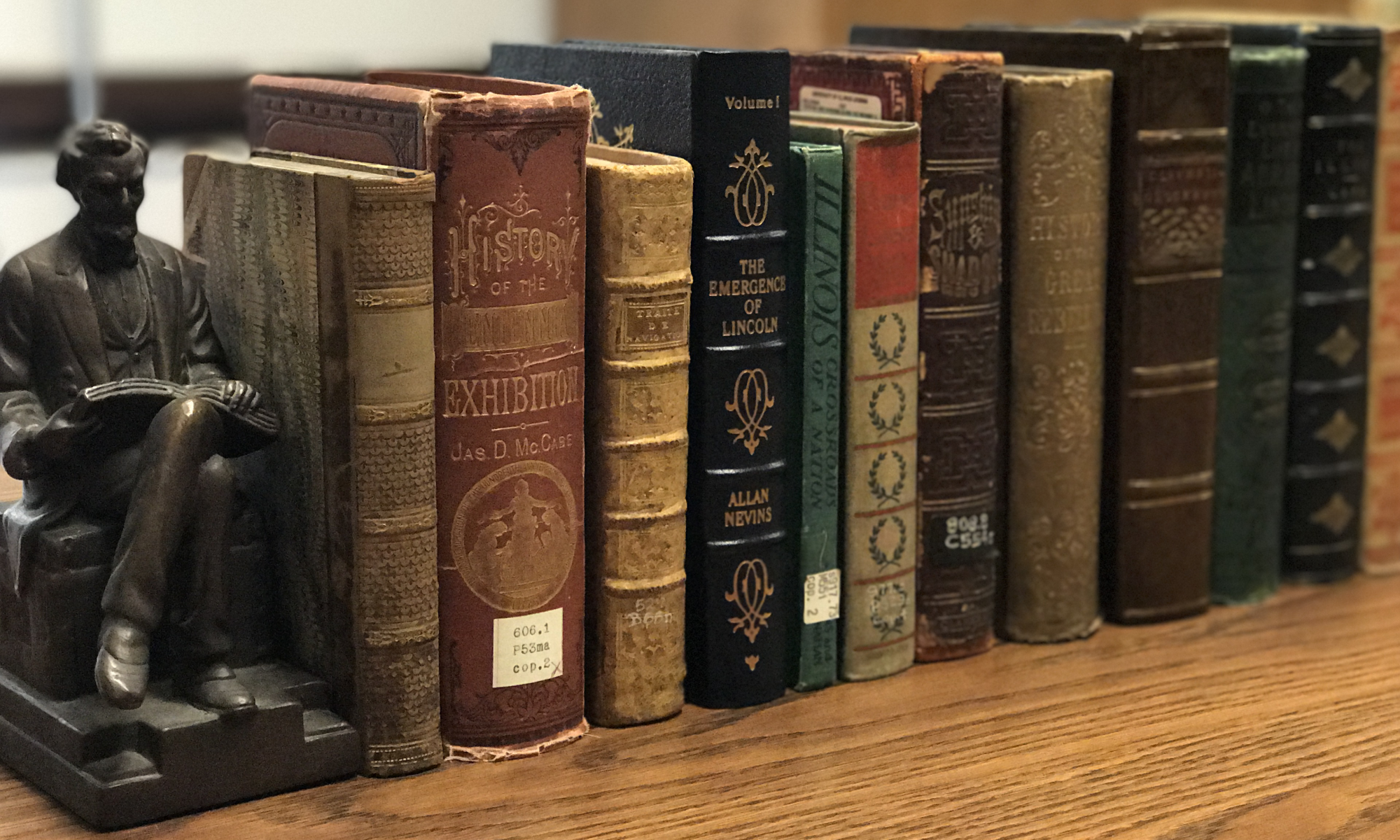

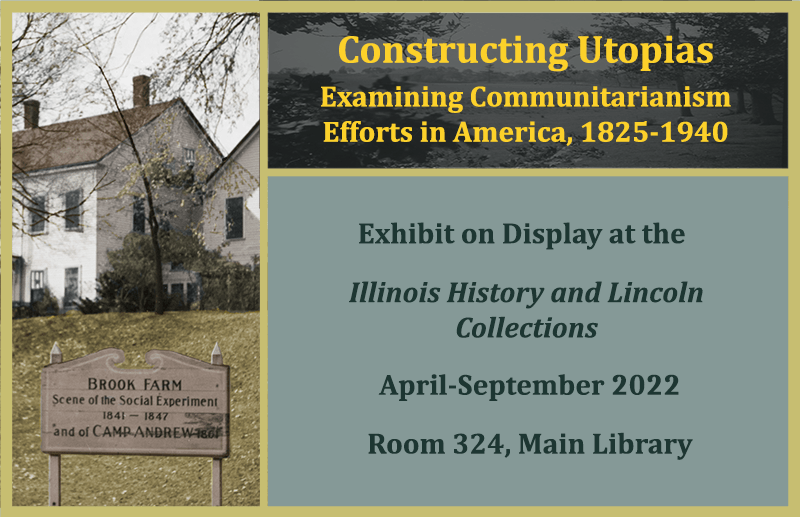

This month IHLC opens its newest exhibit, Constructing Utopias: Examining Communitarianism Efforts in America, 1825-1940, which explores the promotion and study of communitarian colonies in America through research collections and personal papers at IHLC.

This exhibit was originally set for installation in March 2020. Due to COVID-19 pandemic responses and library closings, the exhibit materials have been patiently waiting in crates in the IHLC vault. We are excited to have this exhibit finally installed and available available for viewing during our open reading room hours, Monday-Friday 9am-12pm and 1-5pm (please see our website, library.illinois.edu/ihx, for up-to-date hours).

Read more about the research and curation process in the interview below with Jessie Knoles, who curated the exhibit as a graduate student at the University of Illinois iSchool, and is currently the Lincoln Collection Research Specialist at IHLC.

How did the idea for this exhibit come about?

In October 2019, we received a remote request from a patron looking for a letter Albert Brisbane had written to James Garfield. I had only started my graduate hourly position at IHLC a few months prior, and didn’t know about the Brisbane collection, nor did I know who Brisbane was. As I was looking through a box of correspondence, I started reading some letters Brisbane and his wife Redelia had written to each other. I became fascinated with them, as well as Brisbane’s illustrated tables of industrial systems, art, and the cosmos. I was particularly interested in why a portion of Brisbane’s papers were at IHLC, as it doesn’t fit into our collection scope (Illinois history and Abraham Lincoln).

From there, I found out about communitarianism and began to look more into what it was and how it tied into other collections at IHLC. Brisbane lead me to Arthur Bestor, whose collection really opened the door for exploration. Eventually I realized that it was because of Bestor that we had the Brisbane papers. I knew I wanted to create an exhibit for our reading room, and the breadth of our communitarianism-related materials seemed like the obvious topic.

Where did you begin to decide with your search?

Compared to our other collections, the Bestor collection is huge…about 15 boxes and some boxes are unprocessed. Luckily the finding aid for the Bestor collection is descriptive–I think I started with the Illinois-related materials in Box 7. I looked at most of the collection, trying to piece together the extent of Bestor’s research as well as his process. My curiosity grew as more names and ideas sprung to life—Charles Fourier, Robert Owen, New Harmony (Indiana), Étienne Cabet and the Icarians, Shakers, Bishop Hill (Illinois), Sodus Bay (New York), North American Phalanx (New Jersey), etc.

Bestor researched every communitarian colony in the United States, and expanded his research into religious-based communities like the Shakers. I knew I had to narrow my scope, so I decided to center this exhibit on secular communitarianism (the majority of Bestor’s research), with particular focus on Fourierist and Owenist colonies—those modeled on the theories of French philosopher Charles Fourier and Welsh social reformer Robert Owen.

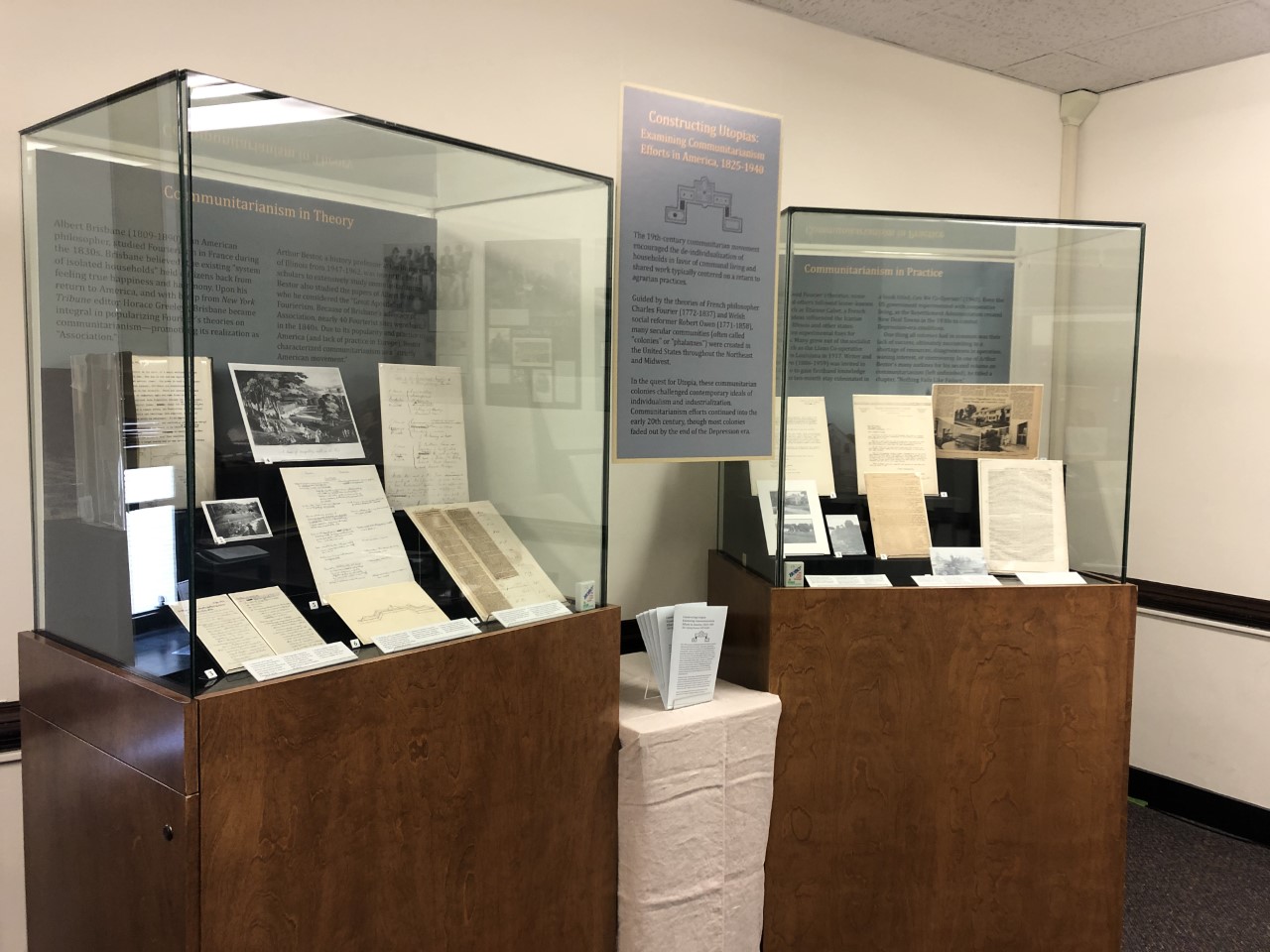

In the end, I decided to divide the exhibit cases up by communitarianism “in theory” and “in practice.” The first exhibit case centers on Fourier, Owen, and Brisbane (the American “apostle” of Fourierism), while the second exhibit case focuses on different communitarian experiments of the 19th and even 20th centuries. The second exhibit case also introduces the qualitative research of Bob Brown, a radical writer and publisher who lived at the Llano Co-operative Colony in Louisiana for ten months starting at the end of 1933. Brown sold his research collection on communitarianism to the University likely due to the University already housing strong collections on communitarianism, like Bestor’s and Brisbane’s.

What was the most surprising thing you discovered?

That exhibits take a lot of work! I started working on this exhibit in early December 2019 by brainstorming which materials in IHLC (a) would tell a complete story and (b) would be visually appealing. Item selection took a lot of work, too. Research collections are particularly dense, so I made sure to be extremely detailed in my notes so that I could return to certain boxes if necessary.

Also, dealing with limited space (two small cases) was harder than I thought it would be. I needed to tell a complete story with only a few items. I started with maybe 30 items I considered displaying and narrowed it down to 16 items. Our cases are much smaller than they look, and I had to make some difficult choices.

Then there’s the exhibit text, which was particularly difficult to execute, as there isn’t much space on our panels for me to explain this 200+ year history of the philosophical theories behind communitarianism, as well as the practice and social implications of it.

The biggest lesson was that creating an exhibit isn’t just the job of the curator. A lot of time and resources go into exhibitions. I worked closely with many colleagues, including the exhibit conservator, Marco Valladares, my supervisor, Krista Gray, and a past undergraduate staff member, Hailey Vasquez, who made all of the exhibit posters and graphics. I appreciate all of the care that went into developing this exhibit!

What is the most interesting thing you’ve learned while working on this exhibit?

I learned how interesting of a person Horace Greeley was. Although he isn’t from Illinois, his name surprisingly pops up within a few of the collections at IHLC (about ten). He’s kind of like Kevin Bacon.* The communitarian movement in America was popularized in large part by his New York Tribune. Greeley gave Brisbane a column to promote “Association” (what Brisbane called the act of living communally), and allowed colonies, including one that existed near where I grew up around Springfield, Illinois, to advertise in the Tribune. It was called the Sangamon Phalanx (later renamed the Integral Phalanx) and existed from 1845-1847.

* “Six degrees of Kevin Bacon” is a game that plays on the assumption that Bacon is the center of the entertainment industry.

What is your favorite thing you have found in your preparation for this exhibit?

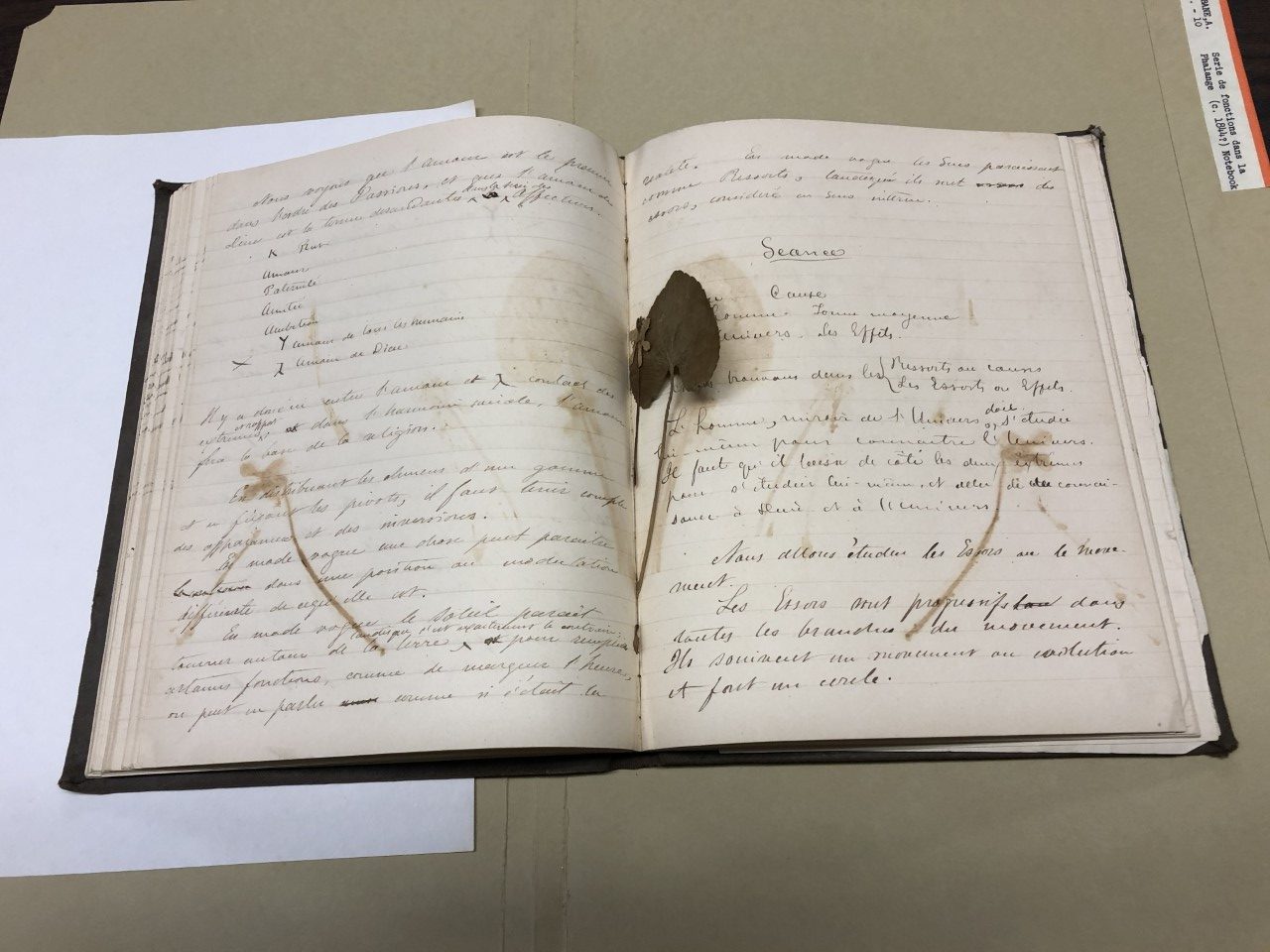

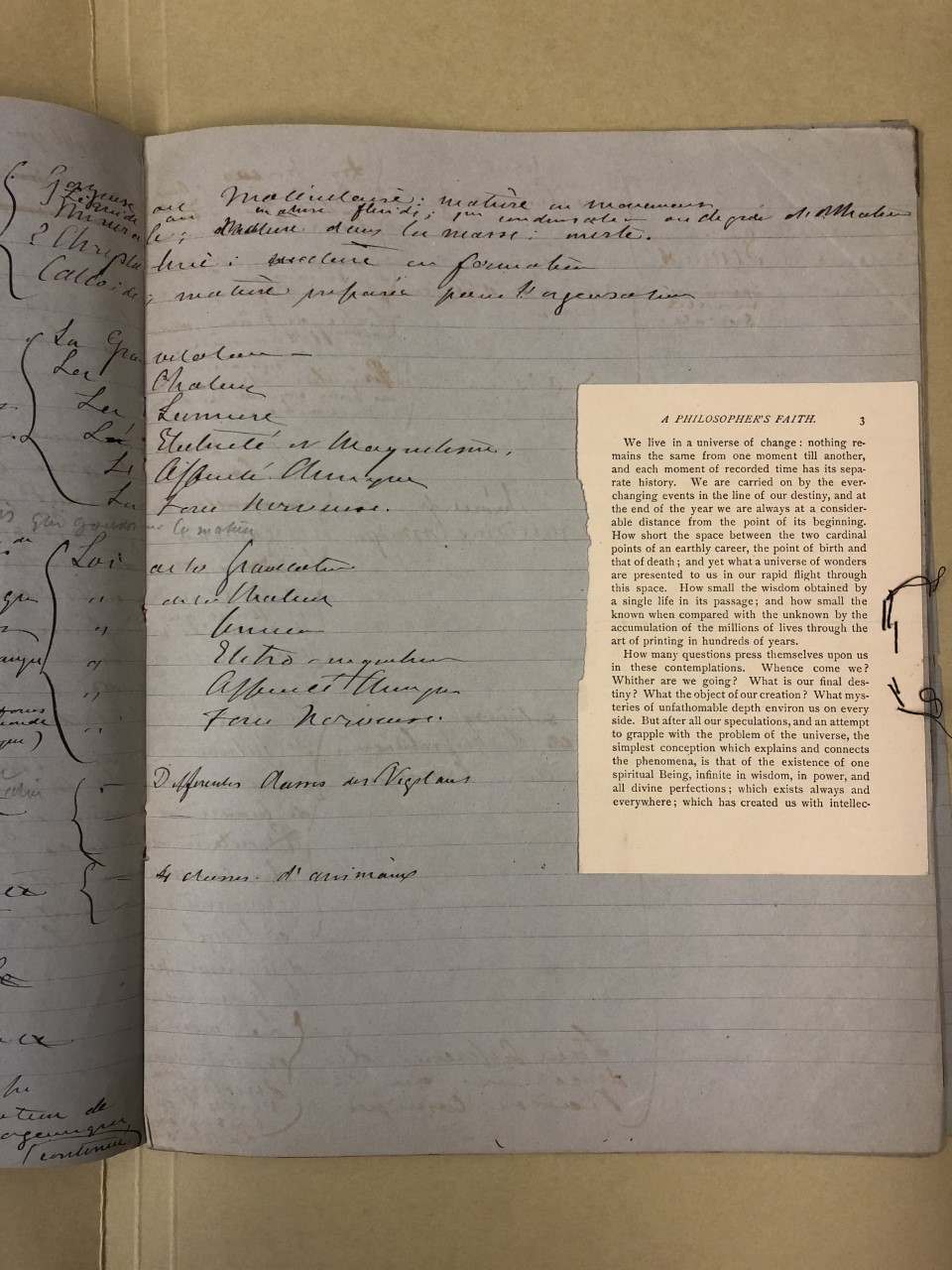

I’m honestly still trying to wrap my head around half of the ideas Brisbane illustrated. My favorite thing I found is actually pretty simple, unrelated to the exhibit, and maybe not terribly interesting to most people – in one of Brisbane’s notebooks (circa 1844) there are pressed leaves. I’m wondering if they’re from Brisbane or possibly from someone else (perhaps his grandson Seward who donated the materials), or even Bestor, who facilitated the donation of this collection to IHLC in 1950.

Brisbane stitching this ephemera into his notebook also fascinated me.

What do you hope visitors take away from visiting this exhibit?

That there is value in research collections. I really enjoyed looking through Bestor’s and Brown’s research files to try to understand how their minds worked, how they organized their thoughts and papers, and how the progression of their research unfolded. Of course, I also learned about their research subjects.

One more thing: although every communitarian experimentation inevitably failed, the foundational philosophies on which they were founded are still relevant: equality of the sexes, the right to find work you find value in, and the importance of education, art, and community.

Resources

MS 468: Arthur E. Bestor Research Collection on Communitarianism, 1935-1962

MS 487: Albert Brisbane Papers, 1830-1832, 1840-1936

MS 492: Bob Brown Research Collection on Communitarian Colonies, 1919-1942

Constructing Utopias: Examining Communitarianism Efforts in America, 1825-1940, is on display in the IHLC reading room through September 2022.