Elizabeth Packard was a reformer in the 1860s and 1870s who advocated for the legal rights of married women and mental health patients. Born Elizabeth Parsons Ware in 1816 in Ware, Massachusetts, she married Theophilus Packard Jr., a Calvinist minister, in 1839. The couple moved to Kankakee, Illinois, and had six children together.

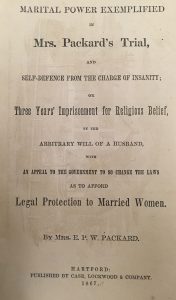

In 1860, Packard’s husband had her committed to the Illinois State Hospital for the Insane based on his personal observations that she seemed “slightly insane” to him. Reverend Packard’s decision to commit his wife stemmed from her expression of religious beliefs that conflicted with his own doctrine. In many states in the 1800s, a husband was legally able to institutionalize his wife, and Packard had no options to challenge his decision. Packard wrote of the account in her 1867 book, Marital Power Exemplified:

I regarded the principle of religious tolerance as the vital principle on which our government was based, and I in my ignorance supposed this right was protected to all American citizens, even to the wives of clergymen. But, alas! my own sad experience has taught me the danger of believing a lie on so vital a question. The result was, I was legally kidnapped and imprisoned three years simply for uttering these opinions under these circumstances.

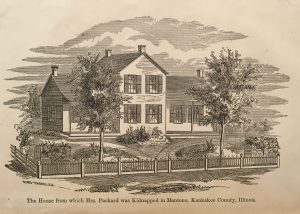

Packard was released in 1863 with a letter from the Asylum stating that she was incurably insane after her oldest children advocated for her release. That same year her husband took it upon himself to lock his wife in the nursery of their home, nailing the windows shut. While it had been perfectly legal for the Reverend to commit Packard to the asylum, he was not legally permitted to confine his wife in her own home. Packard was able to drop a letter out her window describing her predicament, which was then delivered to a friend of hers who appealed to Judge Charles Starr on the issue. Judge Starr issued a writ of habeas corpus that required Reverend Packard to bring his wife to his chambers on January 12, 1864. Reverend Packard brought her, along with the written statement of her incurable insanity from the Illinois State Asylum, and told the judge that he was allowing her “all the liberty compatible with her welfare and safety.” Judge Starr did not find this to be a sufficient justification and scheduled a jury trial to address the issue and determine Elizabeth Packard’s sanity. Reverend Packard, the plaintiff in the case, claimed that his wife’s insanity entitled him to confine her at home, and Elizabeth Packard, the defendant, needed to prove her sanity to regain her freedom.

The judge and jury heard testimonies for each side of the case. Physicians who had spoken with Elizabeth prior to her commitment to the Illinois State Hospital testified against her. One of these doctors, Dr. J. W. Brown, had conversed with Elizabeth under false pretenses, introducing himself as a sewing machine salesman to interview her and assess her mental state. He testified that she had “disliked to be called insane,” and he found her feelings towards her husband and religious beliefs to be evidence of her insanity. The Reverend’s sister and brother-in-law also testified that Packard had tried to distance herself from her husband and the church, both of which they deemed an indication of her insanity.

Elizabeth Packard’s lawyers called neighbors and friends to testify on her behalf, and Packard was permitted to read an essay she had written for a Bible class to share insight into her religious beliefs. Dr. Duncanson, a doctor and a theologian, also testified for Packard’s sanity. He had spent hours talking with Packard and disagreed with Dr. Brown’s understanding of her religious statements, stating that many of her ideas and doctrines were embraced in Swedenborgianism. Dr. Duncanson argued that many intellectuals and theologians in Europe favored these New School doctrines. He went on to describe his impressions from his conversation with Packard:

On every topic I introduced, she was perfectly familiar, and discussed them with an intelligence that at once showed she was possessed of a good education, and a strong and vigorous mind. I did not agree with her in sentiment on many things, but I do not call people insane because they differ from me, nor even a majority, even, of people.

On January 18, 1864, the jury reached a verdict and announced that they found Elizabeth Packard to be sane. Judge Charles R. Starr ordered that Packard “be relieved of all restraints incompatible with her condition as a sane women” to restore her liberty. The Packards never divorced but remained separated for the rest of their lives.

Packard went on to publish books supporting the rights of married women and mental health patients, and she campaigned for legislative reform in these areas, both in Illinois and other states, throughout the 1860s and 1870s. Within Packard’s lifetime, four states revised their commitment laws and Illinois passed a married women’s property law. Packard died in Chicago in 1897.

Packard went on to publish books supporting the rights of married women and mental health patients, and she campaigned for legislative reform in these areas, both in Illinois and other states, throughout the 1860s and 1870s. Within Packard’s lifetime, four states revised their commitment laws and Illinois passed a married women’s property law. Packard died in Chicago in 1897.

You can learn more from Packard’s books in the IHLC holdings, The Prisoners’ Hidden Life, or, Insane Asylums Unveiled (Call number: 362.2 P12p) and Marital Power Exemplified, or Three Years’ Imprisonment for Religious Belief (Call number: 362.2 P12M).

IHLC Resources

Carlisle, Linda V. Elizabeth Packard: A Noble Fight. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2010. Call number: 362.21092 P121c

Other Resources

“Packard v. Packard.” Great American Court Cases, edited by Mark F. Mikula, L. Mpho Mabunda, and Allison McClintic Marion. Gale, 1999. http://proxy2.library.illinois.edu/login?url=https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/greatcourts/packard_v_packard/0?institutionId=386

“Packard, Elizabeth (1816–1897).” Dictionary of Women Worldwide: 25,000 Women Through the Ages, edited by Anne Commire and Deborah Klezmer. Detroit, MI: Yorkin Publications, 2007. http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CX2588818299/GVRL?u=uiuc_uc&sid=GVRL&xid=0aec446c

Himelhoch, Myra Samuels and Arthur H. Shaffer. “Elizabeth Packard: Nineteenth-Century Crusader for the Rights of Mental Patients.” Journal of American Studies vol. 13, no. 3, 1979, pp. 343-75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27553740.

It would seem Elizabeth Packard’s personal crusade for women’s rights in the beginning of the 1860’s (when reading novels, let alone writing them was considered insane behavior for women) helped launch the flood of women authors in 1862 that wrote for the newspapers during the Civil War, which would later produce such works as “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”.

James, thanks for your message! While Packard’s work did affect Mary Todd Lincoln’s ability to advocate for herself, we did not find evidence that they ever met.

Great article.

Question: Can you tell me if Mary Todd Lincoln actually ever met Elizabeth Parsons Packard?

Thank you.

James