Yellowstone is famous for its geology. The park holds more than half of the world’s thermal features. Its surface appearance reflects the activity of a huge caldera that last erupted about 650,000 years ago. The Yellowstone River carves a spectacular canyon, the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, that holds two beautiful waterfalls, 308 and 109 feet high. There are petrified forests atop Specimen Ridge inside the park and in the northern Gallatin range just outside it. Mountains such as the Gallatin, Beartooth, and Absaroka ranges ring the park, and the Red Mountains lie entirely within it.

Despite those riches, geology is an awkward subject for a class on the “Politics of Yellowstone.” The federal government does not have a policy on place tectonics or volcanism. With rare exceptions, we do not have a geyser policy. At the same time, it would be stupid for the course to ignore these wonders. The students rightly want to see this famous geology while they’re in the park.

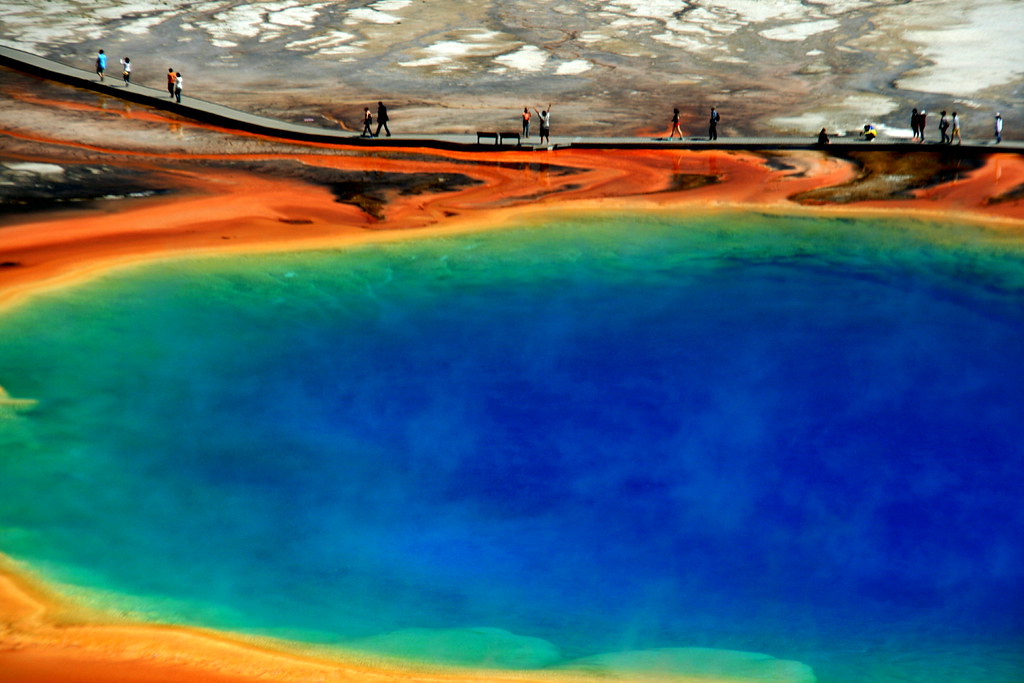

What to do? We use the scenic geology to start talking about tourism. By visiting tourist-heavy destinations like Old Faithful or the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, we examine the impact of tourism development on the environment. Finding a geyser along the trail in an isolated area is very different than viewing Old Faithful from a boardwalk surrounded by hotels, restaurants, gift shops and parking lots.

Our first examination of these issues in 2013 came along a trail I call the “Yellowstone Sampler.” We see some unfenced thermal features in the backcountry and usually walk fairly close to some bachelor bison groups at the north end of the Hayden Valley. After lunch at a scenic spot, we emerge from a moderately-low use trail to the crowds and parking lots of Artist Point. The transition is pretty sudden, which makes it a good place to talk about developed tourism and personal experiences of nature.

The hike encourages students to think about “wilderness” – the Wilderness Act of 1964, students’ personal definitions of nature and of wilderness, and the views of other people. Does wilderness matter to people? Is it important for well-functioning ecosystems? Does the preservation of the world, as Thoreau wrote, lie in wildness?

In 2013, I added a new hike to our second full day in the park. As part of our driving tour of the Lamar Valley’s wildlife, we climbed the lower reaches of Specimen Ridge to reach a petrified forest. This was a remarkably steep trail, posing a definite physical challenge – but one that rewarded us with great views from high above the Lamar. We remained in sight of the park road, but the physical challenge contributed to the wilderness feel of the experience for many students.

Though some guidebooks describe it, Petrified Forest is an unofficial trail, not found on park maps. The Park Service does not maintain it, so people find their own track. This results in many social trails and greater impact on the landscape.

In some parks, there might be a road going up to a site like this. Instead, Yellowstone has decided to keep these petrified trees unpublicized, accessible only by a difficult and unmaintained trail.

Is that democratic? Most visitors – about 97% – want to experience Yellowstone from their automobile or a high-density, paved path. Why do we keep them away from the petrified forest? Automobile sightseers are restricted to a single petrified tree just off the park road, and that tree is surrounded by a fence. Even that lonely tree is inaccessible to recreational vehicles. Is that fair? Or should the park keep some destinations away from the vehicles, recognizing that hikers have some “right” to physical challenge?

When you ask those questions you realize that Yellowstone’s geology starts to open up all sorts of questions about political values. What are national parks for? Who are they for?

Some might argue that Yellowstone should serve the vast majority of Americans who want to go sightseeing only a short distance from their automobiles. Others might emphasize the wilderness experience that can be found only in the larger national parks. Still others might move away from human needs and argue that only large wilderness areas can protect intact, well-functioning ecosystems.

Those are the big topics of the national parks. Geology may not be a politically-salient topic, but it turns out that you can find political themes if you use the geology to play tourist.

If you’re interested in geology, and to some degree even if you’re not, I recommend Geology Underfoot in Yellowstone by Marc Hendrix.

For a fascinating view of the human footprint on the geologic record, see Jan Zalasiewicz’s The Earth After Us: What Legacy Will Humans Leave in the Rocks?