Here at The Rare Book & Manuscript Library, seemingly simple reference questions often turn into much deeper discoveries.That was the case when a patron enquired about our material concerning one Martin F. Tupper. If you aren’t familiar with Martin F. Tupper (1810-1889), then you probably didn’t live in the mid-19th century; if you did, you likely would have ranked him alongside Wordsworth and Tennyson as one of the most brilliant contemporary English poets. Tupper originally rose to fame on the strength of his third book, Proverbial Philosophy (1838), a collection of poetry expressed as quotable wisdom consisting of such gems as “a good book is the best of friends, the same to-day and for ever”(“Of Reading”) and “A wise man in a crowded street winneth his way with gentleness” (“Of Tolerance”).

He was a prolific writer, full of patriotism and religious fervor, and he was always ready with a choice verse for every occasion, such as his paean to the Crystal Palace in 1851 (“Hurrah for honest Industry ! hurrah for handy Skill !”). Part self-help guru and part religious revivalist, he might be considered the Victorian version of Mitch Albom, and he appealed immensely to middlebrow Victorian readers, who devoured his maxims. Alongside his poetry, Tupper also wrote novels and plays, as well as curious fare such as An Author’s Mind: The Book of Title-Pages (1841), sketching out fifty possible books that Tupper envisioned but lacked the time to write. By mid-century, however, Tupper’s star had begun to wane, as critics took him to task for his “empty vanities” and derided his “tea table literature.” By the 1860s, “Tupperism” and other variations on his name had become bywords for overwrought sentimentality and insipid moralization, and continued to be used critically for decades. Today, if Tupper is remembered at all, he is regarded only as an emblematic representation of Victorian culture and morality. What, then, does Tupper have to do with the University of Illinois?

Tupper, like many of his contemporaries, was a devoted scrapbooker, and collected astonishing amounts of letters, newspaper clippings, drafts of poems, and memorabilia concerning both his literary career and his private life. Over the years, he filled some 43 scrapbook volumes, some of which he referred to as his “literary archives,” with these items. By looking at the material he collected and his annotations, researchers find glimpses of some interesting and overlooked aspects of his life, including his friendship with Prime Minister William Gladstone and his campaign on behalf of Liberian independence. These scrapbooks, which were saved by his family, were made available to the biographer Derek Hudson, whose Martin Tupper: His Rise and Fall (1949) is still the only monograph written about Tupper.

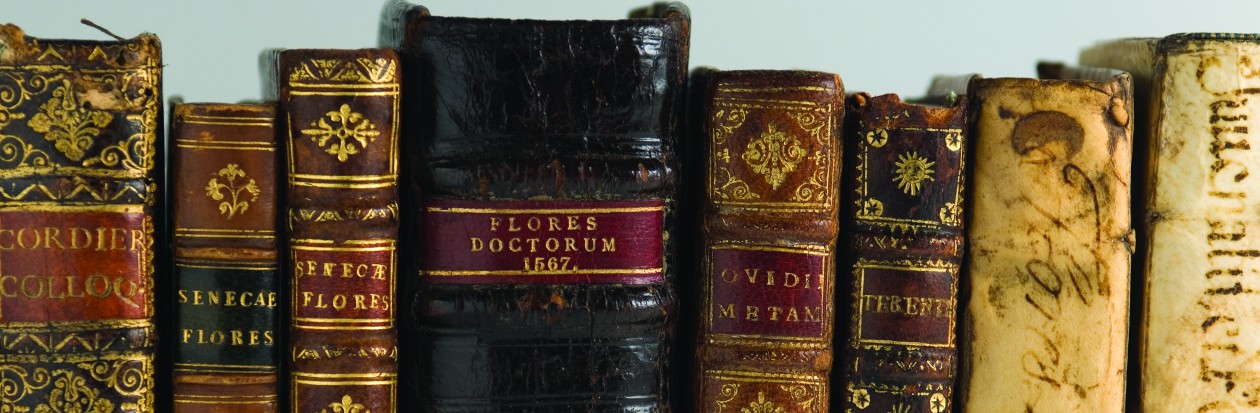

Soon after, however, the scrapbooks were sold, and in 1952 the University of Illinois acquired the entire collection, along with the 106 volumes of Tupper’s collected works originally owned by his son, William Knightson Tupper. The collection also included other miscellaneous items such as Tupper’s journals, passports, and daguerreotypes, as well as Derek Hudson’s handwritten index to his scrapbooks. I suspect that the Tupper purchase was related to the larger purchase of a portion of the archives of Richard Bentley, which the University acquired between 1951 and 1961 (Bentley published many notable Victorian authors, including Charles Dickens—and Martin Tupper).

The scrapbook collection in particular is a buried gem; like many items, it had been hiding in plain sight in our catalogue for decades, but does not appear to have been thoroughly studied by anyone since Hudson. Although scrapbooks are notoriously difficult for libraries to preserve, they are a direct source of material culture, and can provide detailed insights about the culture at large as well as about individual collecting habits. Moreover, Victorian scrapbooking has often been associated with women, and so the Tupper collection provides a good example of a masculine, or even a “professional,” scrapbook.

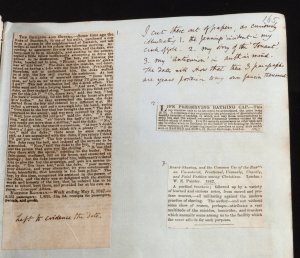

As with many scrapbooks, they can be difficult to muddle through, but I was able to locate several interesting items, including correspondence with Samuel Morse and a sonnet composed in honor of his telegraph; letters about Liberia exchanged with the American President Millard Fillmore; and my personal favorite, a newspaper clipping advertising a “poetical brochure” against the practice of beard-shaving. As Tupper notes in his annotation, his sketch “Anti-Xurion,” published in The Author’s Mind, argued the same thing six years prior.

There are undoubtedly more treasures waiting to be found in Tupper’s scrapbooks, and they will provide a student of Victorian literary and material culture much fodder. BD

The following call numbers at The Rare Book & Manuscript Library pertain to the Tupper collection. Not all of the scrapbooks have been fully catalogued, so please feel free to contact RBML staff for assistance with this material.

Tupper’s collection of scrapbooks and miscellaneous items: 828 T8391.

Tupper’s collection of printed works, taken from his son’s library: 828 T839.

A typescript catalogue of the Tupper purchase: Q. 828 T8391b.

Derek Hudson’s handwritten index to the scrapbooks: 828 T8391sup.