When I was in elementary school, I had a small “Wheel of Presidents”—a device consisting of two cardstock circles affixed to each other in the center, one smaller, with a wedge-shaped cutout, and one larger, with miniature portraits of the U.S. presidents dotting its circumference. I don’t remember how I acquired it, but I do remember playing with it, turning the smaller, upper circle so that the cutout would align with one of the presidents on the rim of the larger, lower one and reveal the few facts about his presidency printed below his portrait. Although I did not know it at the time, my “Wheel of Presidents” was far from novel or unique. Rather, it represented just the most recent incarnation of a pedagogical tool whose origins were far older than my days in elementary school—far older, even, than the U.S. presidency.

The idea of organizing information in rotating charts dates at least to the incunabula era. Early astronomy books often featured paper or parchment wheels called volvelles as a way of helping students learn the motions of the planets, moon, and sun. Later, wheels morphed into calculation tools that could aid their users in finding the positions of stars, solving logarithmic equations, determining the dates of eclipses, and more.

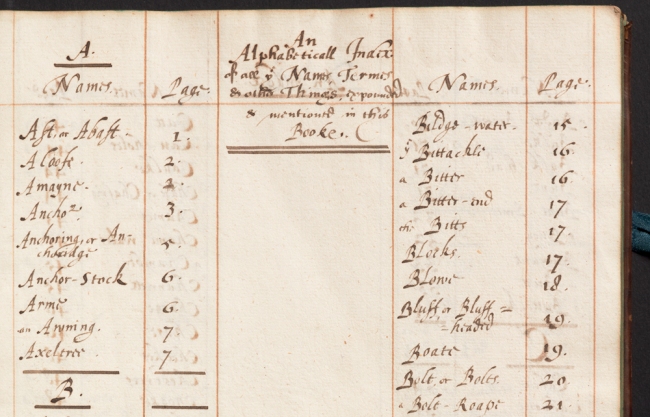

Although The Rare Book & Manuscript Library holds many fine examples of books that include wheels as pedagogical aids, one in particular caught my eye: The First Part of the Principles of the Art Military Practifed in the Warres of the United Netherlands (Q. 355.009492 H511p 1642), printed in Delft in 1642. All of the other circular charts I had seen related somehow to astronomy–what was one doing in a military handbook? I had to know.

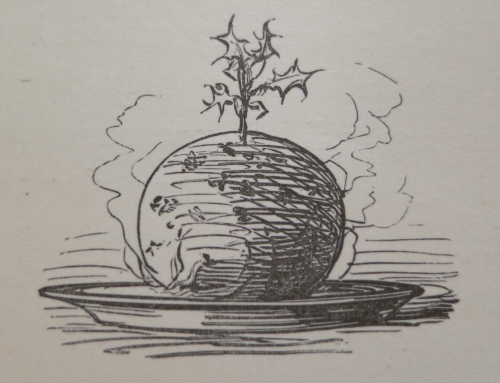

As he notes in his dedication to Prince William of Orange, Quartermaster Henry Hexham, the author of the Principles, felt a desire to pass on some of the knowledge and experience he had gained during his “two and fortie yeares” of service in the Dutch military. This led him to compose the Principles, a manual that he hopes will serve “for the inftruction of fuch English Gentleman, & Souldiers, who are willing to come into the States feruice, & for the informing of their Iudgments the better.” To this end, Hexham includes in the manual information on the duties of each member of a foot company, armor and weapons, various methods of holding a pike and musket, and the exercises and motions through which captains would lead their foot companies. It is this last section where the wheels come in. Hexham accompanies the more basic exercises with static diagrams of a foot company in rank and file. For some of the more complex troop movements, he removes the images of the foot company to separate, small pieces of paper, which are fixed on the page in such a way that they can rotate. Spinning the pieces of paper one way or the other then allows readers to see the results of a particular command, like “To the left hand.” Though the pieces of paper themselves are actually rectangular rather than circular, they nevertheless demonstrate the power of interactive, rotating devices as instructional tools, especially when the subject to be taught involves complex movements—whether they be of heavenly bodies or earthly ones. BS

The First Part of the Principles of the Art Military Practifed in the Warres of the United Netherlands. Shelfmark: Q. 355.009492 H511p 1642

The First Part of the Principles of the Art Military Practifed in the Warres of the United Netherlands. Shelfmark: Q. 355.009492 H511p 1642