While we were improving the minimal cataloging of our medieval and early modern manuscript holdings, we came across a hand-written copy of one of the earliest specialized English Dictionaries, Henry Manwayring’s Seaman’s Dictionary. Since our library boasts an amazing collection of early English dictionaries, we were not overly surprised. It is always pleasant to see examples of industrious lovers of books copying out the text from printed books in the days before xeroxing. The layout mimics the printed text of 1644, the entries appeared to be the same, and it even included the author’s preface. But wait, this manuscript predates the printed text! More on that in a moment.

The 1644 printed text is considered the first authoritative treatise in seamanship in English. It was written by Sir Henry Manwayring, a famous seaman of the Jacobean era, who happened to be an infamous pirate for a few years. Manwayring was a Shropshire lad, born in 1587. And lest you think your own children or grandchildren are precocious, consider Manwayring, who matriculated at Oxford at the age of 12, received his B.A. three years later, and was admitted to the Inner Temple as a lawyer at 17. He soon became a naval officer, chasing pirates in the British Channel and off the coast of Newfoundland. But a few years later, he took offense when King James I buckled under Spanish pressure and prevented him from fulfilling one of his naval missions. He took out his frustrations on the Spanish, becoming a notorious pirate on the Barbary Coast. He bedeviled the Spanish navy for several years and annoyed the French with his swashbuckling, though he claimed never to have attacked English ships.

Fearing reprisals from France and Spain, King James eventually offered Manwayring pardon if he gave up piracy. He came back to England in 1616, received knighthood in 1618, and dedicated his “Discourse on Piracy” – an insider’s perspective, obviously – to the King. In that book, by the way, he warns the King against granting pardons to pirates. He later served in Parliament and received an honorary doctorate of physics from Oxford. Needless to say, there is more to tell about our pirate-knight, but let’s get back to our manuscript.

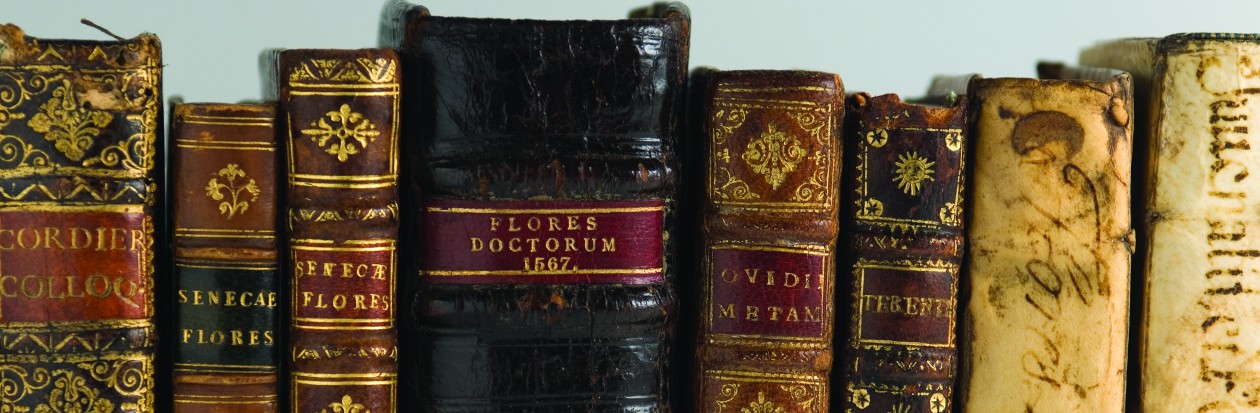

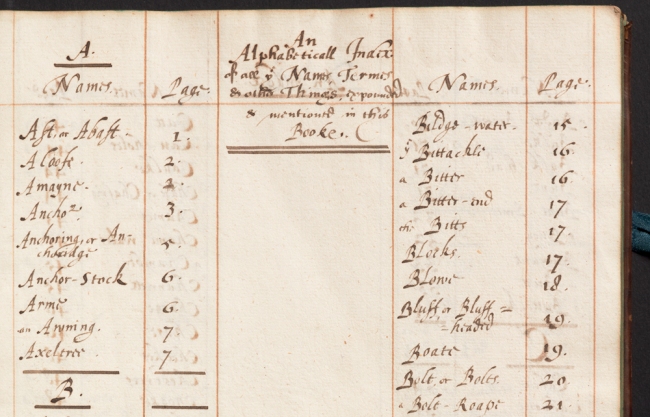

The 1644 imprint is very small, just 20 centimeters, a handy vademecum for a sailor to carry on board. Though small, there is a bit more text on the title page of the printed book than the folio manuscript, but that’s to be expected since it includes publication information. The manuscript is twice the size and the title is a little different: “A Briefe Abstract, Exposition, and Demonstration of all Termes, Parts, and Things Belonging to a Shippe, and The Practick of Navigation.” Manwayring is noted as the author.

Suddenly, the date in the lower right corner catches the eye. 1626? But this is a copy of a book that was first printed in 1644. We soon learn that Manwayring appears to have written the Seaman’s Dictionary while serving at Dover Castle from 1620 to 1623. Clearly, this is one of those texts, so common in early modern literature, which circulated in manuscript before it appeared in print. And sure enough, there seem to have been at least 14 manuscripts of the text in circulation from 1620 to 1644.

Looking at our manuscript again, we see that the scribe has signed and dated it, and we see that his name is Raph Crane. This is when our hearts beat a little faster because, as denizens of one of the best Elizabethan and Stuart drama collections in America, we know that Raph Crane was a scrivener for the King’s Men at the Globe Theater. He is generally thought to have been the scribe for at least five of the fair copies of Shakespeare’s plays that appear in the First Folio.

Of course the date is 1626, ten years after Shakespeare’s death, but the connection is still there. Scholars always want more evidence for Crane, more examples of his penmanship, and here it is in our manuscript. Though ours is the only one signed, four other extant manuscripts have been attributed to Crane’s hand.

So, what to make of it all? This little encounter with an interesting manuscript in our collection not only introduced those of us not up on our Jacobean naval history to Henry Manwayring and his important early English dictionary, but this bibliographic adventure also provided further evidence for the common practice of circulating books in manuscript in the 17th century; clarified for the world exactly which copy of Manwayring’s dictionary we hold; and provided Renaissance scholars with another example of Raph Crane’s handwriting. We have digitized the manuscript and already two researchers in England are working on it. VH