Musee retrospectif de la classe 90. Parfumeries (matieres premieres, materiel, procedes et produits) a l’exposition universelle internationale, a Paris. Rapport de M. le comte Robert de Montesquiou[Retrospective Museum of Class 90. Perfumeries (raw materials, equipment, processes and products) at the universal, international exhibition, in Paris. Report by Count Robert de Montesquiou.]

The bureaucratic-looking title is barred by a bold inscription in purple ink, in the unusual, flourishing handwriting of Robert de Montesquiou, a well-known, if misunderstood figure of the Belle Epoque.

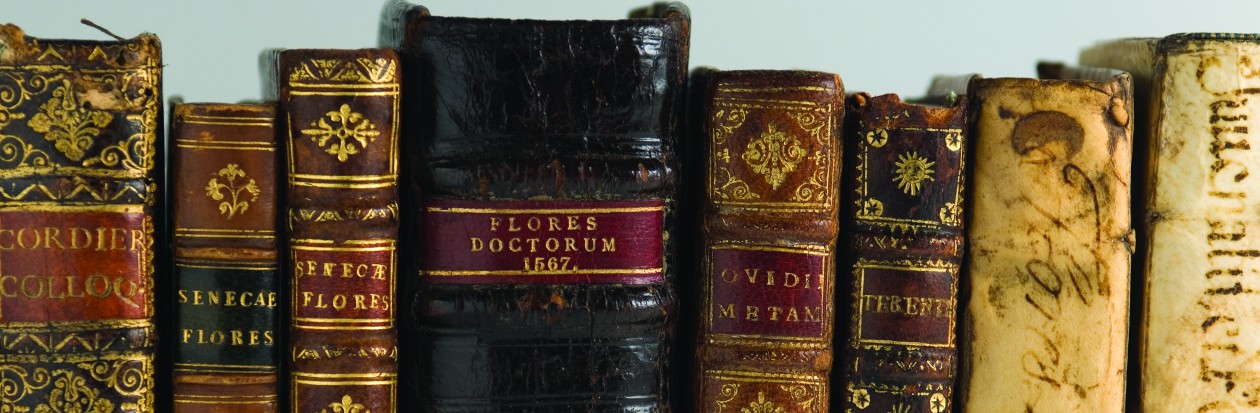

Born in one of the oldest families of the French nobility, Comte Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac (1855-1921) was a prolific poet, novelist, art critic, chronicler, memoirist, as well as a designer, book collector and patron of the arts. He had ties with countless authors, artists, composers and craftsmen of the time. He was portrayed by numerous artists, including Laszlo, La Gandara, Whistler, and inspired characters in books by J. K. Huysmans, Jean Lorrain, and, most notably, Marcel Proust. His origins, lavish lifestyle and colorful personality contributed to his reputation as a ‘dilettante’, which prevented him from being recognized as the original and talented creator that he was. Montesquiou was a lifelong friend of Proust and served as a mentor before he was surpassed by his pupil, who borrowed some of his traits for his character, Charlus. Their correspondence, held in part in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library’s Proust collection, is peppered with references to Montesquious many publications, most of which can be found at Illinois either in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library or the Kolb-Proust Archive for Research. While they were primarily acquired to support the Professor Philip Kolb research on Proust’s correspondence, they constitute a rare collection of works by an author who was also a bibliophile and an important patron of binders and other book artists of his time.

This book is one of many Musées rétrospectifs published in the wake of the 1900 Paris World Fair, whose mission was to present all domains of knowledge, science and technology in one location. A detailed classification arranged disciplines into twenty groups, which were further subdivided into numbered classes. “Parfumerie”, belonged to class 90 of the chemical sciences group. The planning committee for that class was composed of influential members of the French perfume industry, including Victor Klotz, owner of the Edouard Pinaud perfumery, whose collection of perfume bottles and beauty-objects made up the bulk of the retrospective exhibition at the World Fair.

This Musée rétrospectif is closely related to another book by Montesquiou housed in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library: Pays des Aromates, of which only 150 copies were printed. Pays des Aromates was commissioned by Mme Victor Klotz on the occasion of the World Fair exhibition, according to biographies. The Musée rétrospectif incorporates a tamer version of Pays des aromates, from which biting anecdotes about thinly veiled contemporaries have been excised.

Pays des aromates (Land of Scents) provide an overview of perfume usage from Antiquity onward, followed by a detailed commentary of the show, and a detailed catalog of all objects and books from the Victor Klotz collection. The Musée rétrospectif follows the same template, with added descriptions of a few objects and books contributed by other collectors. (Proust reviewed “Pays des aromates” in Chronique des Arts et de la curiositéon 5 January 1901)

Because the Musée rétrospectif is undated, biographers have assumed that it was published at the time of the Fair, which opened on April 15, 1900, and that it therefore preceded Pays des Aromates, which is dated July 10, 1900. The Musée, however, contains a nod to the poem Le coeur innombrable by comtesse Anna de Noailles, whose book first appeared in May 1901. Bibliographie de la France – Journal général de l’imprimerie et de la librairie, which records all books received under French legal deposit laws in biweekly installments, lists Pays des Aromates in its August 18, 1900 issue, while the Musée rétrospectif doesn’t appear until the November 14, 1903 issue, along with a dozen other Musées rétrospectifs of the 1900 World Fair.

Abel Hermant (1862-1950), the recipient of this particular copy of the Musée rétrospectif, was a novelist, playwright and satirical observer of fin-de-siècle Parisian society. He was the brother of Jacques Hermant, the architect in charge of the various “musées centenaux” at the Paris World Fair. Montesquiou, who was famous for his wit, once wrote about Hermant: “L’écrivain le plus charmant, c’est Abel au bois d’Hermant” (“The most charming writer, is Abel Hermant”), which plays on Hermant’s name and “La Belle au Bois Dormant” (“Sleeping Beauty”). The dedication features another play on “pois de senteur” (“sweet peas” or, more literally, “scented peas”). This alludes to the flower of the sweet pea plant and also suggests that each item in the catalog is its own “pea” of “scent”:

à Monsieur Abel Hermant, ces pois de senteur. Comte Robert de Montesquiou

*****************************************************************

Bibliography

Willa Z. Silverman. « Unpacking His Library : Robert de Montesquiou and the Esthetics of the Book in Fin-de-siècle France ». Nineteenth-Century French Studies, vol. 32, issue3&4, Spring-Summer 2004, pp. 316-331

Antoine Bertrand. Les Curiosités esthétiques de Robert de Montesquiou. Genève : Droz, 1996 (2 vols.)