Indexed by Courtney Richardson

Indexed by Courtney Richardson

Indexed by Courtney Richardson

Indexed by Courtney Richardson

Indexed by Courtney Richardson

Indexed by Courtney Richardson

Indexed by Courtney Richardson

Synopsis by Madeleine McQuilling

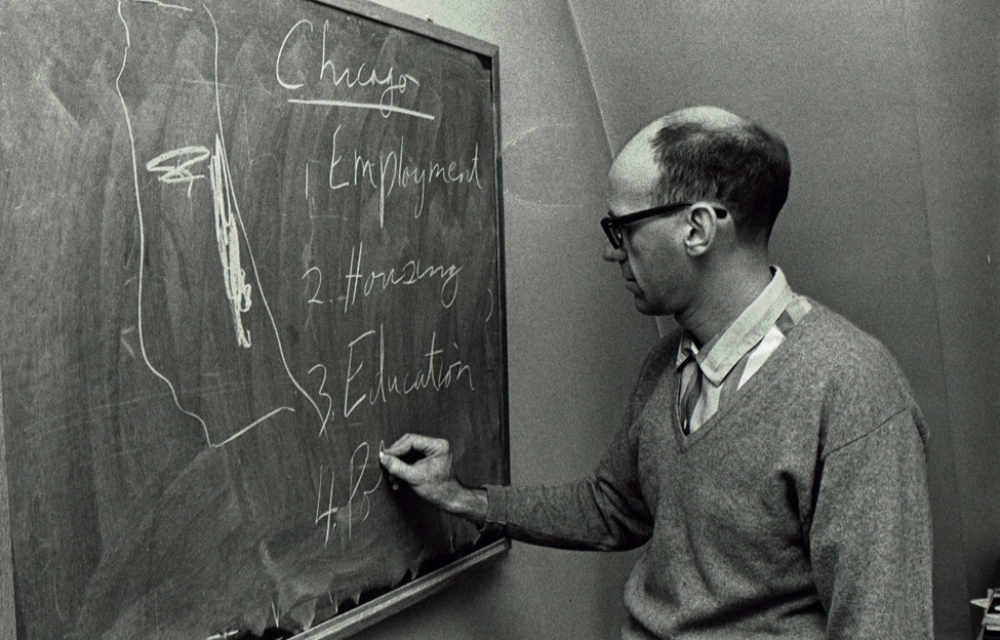

In this chapter, Hal Baron spends a few pages on each of his main themes (history, housing, labor, education, politics) and explains how they all represent different aspects of what he terms the “web of urban racism.” The web of urban racism, a phrase Baron uses in his writings from the late 1960s onwards, denotes the network of institutional racism intrinsic to American society (1). Baron explains:

The impersonal institutions of the great cities have been woven together into a web of urban racism that entraps Negroes much as the spider’s net holds flies – they can wiggle but they cannot move very far. There is a carefully articulated interrelation of the barriers created by each institution. Whereas the single institutional strand standing alone might not be so strong, together the many strands form a powerful web. But here the analogy breaks down. In contrast to the spider’s prey, the victim of urban racism has fed on stronger stuff and is on the threshold of tearing the web.

Written in 1968, Baron’s sympathies for the black power movement surge beneath his calm prose. The “Long, hot summer of 1967” shone a spotlight on the problematic race relations in America; by its light, the web of urban racism becomes more visible, and thus, more vulnerable. Baron is confident that its victims have “fed on stronger stuff,” and are now capable of “tearing the web.” In order for readers to fully appreciate this anticipated moment of liberation, Baron details how the web of urban racism came about, and how it continues to impact every sphere of daily life.

Baron starts his history of urban racism in America with the Civil War, declaring that the “abolition of slavery did not mean the abolition of racism.” To the contrary, the racism decreased only in its visibility, taking “on a new institutional form in which it was still effective in subjugating blacks and politically disarming poor whites.” In other words, the racism starts shifting from de jure to de facto. Baron sees de jure segregation, or legalized segregation, as a largely southern system; in contrast, he considers de facto, or automatic segregation a predominantly northern one. But, Baron observes, “as the southern population becomes more demographically similar to the northern population, the nature of racism is beginning to assume greater similarities, especially in metropolitan centers.” The difference between de jure and de facto segregation is the difference between a school that forbids the enrollment of black students, and a school built in such a way that no black students live within its district. The great migration of the early 20th century made it painfully clear that racism survived the Civil War; it was alive and well––northern as well as southern.

For Baron, the demographic shift represented a “push-pull phenomenon.” “The push,” he argues, “was the displacement of Negroes from southern agriculture, occasioned first by soil exhaustion, then by boll-weevil destruction and crop diversification.” The labor opportunities in the agricultural south were further diminished by the rise of tractors, herbicides, and agricultural machines. “The pull of the city,” Baron continues, “has primarily been exerted through wartime labor shortages,” and the demand for unskilled labor that they occasion. The northern cities further appealed to black people because their system of de facto racism was “less obvious than the South’s Jim Crow.” Baron emphasizes that the demographic shift from rural to urban spaces is just as important as the one from south to north. This urbanization is important to Baron, because: “The great racial conflict now so manifest in the city is both generated and restrained by its major institutions.” “Indeed,” as Baron declares in no uncertain language, “the white suburban noose around the city is drawing tighter.”

In this report, Baron advances the thesis that de facto segregation is actually worse than de jure segregation: “As the specific barriers become less distinctive and less absolute, their meshing together into an overriding network compensates so that the combined effect of the whole is greater than the sum of the individual institutions.” Baron clarifies:

For examples: the school system uses the neighborhood school policy which combined with residential segregation operates as a surrogate for direct segregation; suburbs in creating very restrictive zoning regulations, or urban renewal developments in setting universally high rents can eliminate all but a very few Negro families on the basis of income; given the racial differentials produced by the school system, an employer, by using his regular personnel tests and criteria, can screen out most Negroes from desirable jobs.

This is the web of urban racism. Although these racial controls represent a web from a structural standpoint, “from within the Negro community,” Baron explains, “it tends to appear that there is just a massive white sea that surrounds a black island.” This analogy brings to mind Du Bois’ cave allegory in Dusk of Dawn (or Myrdal’s reference to it in An American Dilemma), while echoing Martin Luther King’s “lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity” (2). As though to emphasize this socioeconomic aspect, Baron now moves from a broad discussion of the web of urban racism to its role in the dual labor market specifically.

While the education gap between black and white workers had nearly closed by the 1960s, the gap in salary, employment, leadership opportunities, and socioeconomic status has only grown. Baron notes that even “the United States Department of Labor has had to conclude that ‘social and economic conditions are getting worse, not better’” for people trapped in slum sectors. For Baron, this inequality results from a dualism in the labor market that divides job openings along racial lines. Contrary to other reports at the time, the Chicago Urban League’s “own studies indicate that the Negro job-seeker is quite the rational economic man,” and thus the financial discrepancy exists “because the black worker faces a very differently structured set of opportunities” than his white counterparts. Baron elaborates:

In effect, certain jobs have become designated as “Negro” jobs. Negro workers are hired by certain industries, by particular firms within these industries, and in particular jobs within these firms. Within all industries, including government service, there is unmistakable evidence of occupational ceilings for Negroes. Within establishments that hire both Negro and white, the black workers are usually limited to specific job classifications and production units. An accurate rule of thumb is that the lower the pay or the more disagreeable and dirty the job, the greater the chance of finding a high proportion of Negroes.

This dual labor market works in tandem with the dual housing market to keep black people financially subordinate.

It goes without saying that ghettos are suboptimal places to live. As Baron clarifies: “The ghetto is bad not because it is inhabited by black people, but because it operates as a subjected enclave.” It exists specifically to trap black people, both physically and psychologically. As Baron proves for the Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority case, many black families have little to no choice in their housing arrangements. “Overwhelmingly,” he explains, “real estate brokers refuse to show Negroes properties outside the ghetto or transition neighborhoods. Lending institutions refuse to grant them mortgages for properties beyond these confines.” Furthermore, the CUL found that housing units in the Chicago ghettos cost 10% more than comparable housing in white sectors. This so-called “color tax” extends to retail prices, allowing “merchants operating in the ghetto [to] charge more for goods and credit or sell inferior quality merchandise at regular prices.” When the lower wages and higher cost of living cause black people to depend upon welfare, “the bureaucrat machinery” degrades and infantilizes them, treating them “like wards of the state, rather than responsible adults.” The web of urban racism intentionally erodes black peoples’ power and credibility; the housing market threads are perhaps the most insidious, as physical location dictates one’s political and educational opportunities.

Neighborhood school districting and gerrymandering systems prevent conditions in the ghetto from improving. As Baron remarks, “educational institutions which provide markedly different [inferior] results for black and white children are key to the structure of urban racism.” Children of black workers are almost always districted to underfunded, overcrowded schools, whose students lag years behind their white peers, thus trapping them in the same unskilled labor market as their parents. “Educational systems have become a major pillar of racism,” Baron observes, “precisely because education has become so important in the total scheme of our society.” That said, Baron is far more concerned about the psychological impact these schools have on their students than he is with reduced academic achievements. For Baron, ghetto schools exist “as extremely efficient training institutions” designed to instill in black children the role of “a subordinate ‘Negro.’” These children grow up surrounded by middle class black teachers and principals who can only maintain their positions of relative power by inculcating their “lower status black charges with the idea that they are unteachable.” This environment “conditions the individual Negro youngster to expect a subordinate position for the rest of his life” and so he is not surprised to find the exact same pattern in the political sphere. Baron describes how black office holders can be elected (in predominantly black districts), but that any effort to improve the lives of their black constituencies represents career suicide. “Even where skillful politicians have risen to the top, as in Harlem with J. Raymond Jones and Adam Clayton Powell,” Baron explains, “they have been cut down or circumscribed basically because they were black.” From this, Baron concludes that people working within urban institutions are unable to dismantle the web of urban racism precisely because they themselves are trapped inside it.

“The Web of Urban Racism” is one of the last reports Baron wrote for the Chicago Urban League, as he left later that year. This document––which is uncharacteristically radical for the CUL––shows Baron’s shift from the integration model of the civil rights movement to the more radical one of black nationalism. Indeed, Baron argues that the student led black power movements have the greatest chance of tearing through the web. “Today, under the slogans of ‘black pride’ and ‘black consciousness’” Baron observes, “we are witnessing a revolution in the role expectations of high school and college students.” They are disrupting the whole racist system by categorically refusing both the role of unteachable student, and that of token official. Baron explains that, “the development of these new role concepts will bring the black youth into conflict with the racist norms and methods of operation in our major institutions,” and in doing so, places them on the “the threshold of tearing the web.” Baron believes that the success of these youth led movements will “depend upon the social, economic and political strategies” implemented, which is perhaps why he supported Detroit’s League of Revolutionary Black Workers after a short stint as a research associate at Northwestern University.

In the final section, Baron draws on W.E.B. Du Bois to detail a possible future in which black and white cultures exist symbiotically. He explicitly rejects “the assumption that the dominant white society, which exercises racism’s controls, is the healthy organism into which the sick ghetto should dissolve.” Baron concludes the article with this evocative, prophetic paragraph:

White men and black men are locked together in this nation so that they determine one another’s fate. Since the day has come when the darker brother will no longer suffer trustingly like Job, a new destiny awaits them both. Racism’s cancer, disturbed by the resistance, can feed upon itself and bring greater destruction in its wake. Or, the healthy elements in the two cultures can contend and react upon each other, creatively transforming themselves in the process. The one possibility denied to each culture is to operate in isolation as though the other were not there.

This message of hope, tempered as it is with Old Testament style warnings, rhetorically places both white and black cultures on equal footing. They are both valid, they are both locked, and both of their fates will be impacted by the other.

END NOTES:

1.Hal Baron uses the phrase “web of urban racism” in the following works––“Public Housing: Chicago Builds a Ghetto” (1967), “Negroes in Policy-Making Positions in Chicago: ‘A Study in Black Powerlessness in Chicago’” (1968), “Report on the Chicago Urban League, Annual Meeting 1968,” “The Demand for Black Labor: Historical Notes on the Political Economy of Racism” (1971), “Building Babylon: A Case of Racial Controls in Public Housing” (1971), “Institutional Racism in Modern Metropolis” (1973), “Racism Transformed: The Implications of the 1969s” (1982).

2.W.E.B Du Bois cave analogy:“It is difficult to let others see the full psychological meaning of caste segregation. It is as though one, looking out from a dark cave in a side of an impending mountain, sees the world passing and speaks to it; speaks courteously and persuasively, showing them how these entombed souls are hindered in their natural movement, expression, and development; and how their loosening from prison would be a matter not simply of courtesy, sympathy, and help to them, but aid to all the world. One talks on evenly and logically in this way, but notices that the passing throng does not even tum its head, or if it does, glances curiously and walks on. It gradually penetrates the minds of the prisoners that the people passing do not hear; that some thick sheet of invisible but horribly tangible plate glass is between them and the world. They get excited; they talk louder; they gesticulate. Some of the passing world stop in curiosity; these gesticulations seem so pointless; they laugh and pass on. They still either do not hear at all, or hear but dimly, and even what they hear, they do not understand. Then the people within may become hysterical. They may scream and hurl themselves against the barriers, hardly realizing in their bewilderment that they are screaming in a vacuum unheard and that their antics may actually seem funny to those outside looking in. They may even, here and there, break through in blood and disfigurement, and find themselves faced by a horrified, implacable, and quite overwhelming mob of people frightened for their own very existence.” W.E.B Du Bois. Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept. Edited by Henry Louis Gates Jr. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 66.

(Synopsis by Donald Planey)

In this Chicago Urban League Study, Dr. Baron direct a CUL research team-headed by himself, and consisting of research assistants Harriet Stulman, Richard Rothstein, and Rennard Davis-in studying the attainment of decision-making positions within the Chicago Metropolitan Area’s major institutions. Examining corporations, law firms, unions, public school systems, local government, religious organizations, universities, and the Democratic Party, this empirical study draws from 1965 Census data, interviews by research assistants, and publicly-available information about various institutions’ rosters.

Here, Baron and his team examined a relatively straightforward empirical question: Which types of organizations in the Chicago metropolitan area tended to exclude Black people from decision-making posts, whether top-or mid-tier, and to what degree? The study finds that Black Chicagolanders are widely shut out of decision-making positions, but that there is a great deal of variegation in how different segments of the region’s institutions practice exclusion (or in rare cases, inclusion). The Democratic Party, CIO unions, and religious organizations are more likely to accept “above-token” Black leadership, while different segments of public, private, and civil society either entirely exclude Black people, or alternatively, accept “token” amounts of Black members into mid-tier leadership positions.

Towards the end of the article, Baron analyses the data, delineating the challenges of attaining “Black power” in the Chicago region. In turn, he implores the reader to consider the challenges of defining the purpose of attaining Black social, economic, and political power, especially within the confines of a class-stratified social order.

Synopsis by Donald Planey

In the unpublished manuscript “The Menace of American Fascism,” Baron explores the possible historical conditions under which the United States could potential undergo a turn towards fascist politics. Using and clarifying his approach to radical institutionalism, Baron conceptualizes the U.S. social fabric as a set of class and race formations set against the backdrop of the moving terrain of the post-war labor market. To explore the future dangers of a reactionary turn in American politics, Baron examines the politics and social base of the 1968 George Wallace campaign, as well as the reasons for Nixon’s ultimate victory over Hubert Humphrey. Instead of the dominant contemporary approach to radical institutionalism represented by C. Wright Mills, which was dedicated to uncovering the “power elites” within the U.S. business-state nexus, Baron’s institutionalism was dedicated to studying the ways in which different class-race formations attempted to secure their social standing amid an unraveling post-war social contract.

In Baron’s analysis, post-war growth in inequality is concomitant with an increasing sense of distance from the U.S. political system among Americans. Due to racial divides within the United States, this alienation has manifested in different ways between the white and Black working classes. While the Black working class was at the height of its support for civil rights and Black liberation, the white working class was torn between economic populism and white supremacy. While Baron notes that Wallace’s politics resemble the original European fascist movements in key ways, he views the U.S. bourgeoisie as equally complicit in opening up possibilities for fascist reaction against Black liberations and growing white impoverishment.

Fascism, in Baron’s understanding, is enabled by structural and institutional conditions at specific junctures in a nation’s economic development, not just the presence of fascist ideology among certain individuals. The U.S.’s founding mythology valorizes the white yeoman entrepreneur and worker. However, white conservatism’s free market convictions (embodied by Barry Goldwater) also inhibited the formation of an effective social base for an American fascist movement, by throwing cold water on the desire of more Wallace-type conservatives to construct a supportive welfare state for white Americans. However, these did not simply reflect different factions of white conservatism. White Wallace-style populists still viewed themselves as committed to a free market. But if mainstream elites were to begin valuing “security” over freedom, and white populists were able to square the circle of white-only egalitarianism, a space could open up for a genuine American fascism within the U.S. civil society.

Synopsis by Kurtis Kelley

In The Demand for Black Labor, Baron expertly guides the reader through a historical narrative of Black Americans’ relationship with the ‘economic base of racism’ to provide insight into their oppression within the modern capitalist system. For Baron, the position of Black workers and trajectory of Black labor is governed by two major forces: ‘the laws of capitalist development, and the laws of national liberation’. While Baron focuses his analysis on capitalist development and its effect on the historical demand for Black labor, his acknowledgment of the saliency of Black Nationalist politics and liberation is a vital thread of Baron’s essay. From slavery into the present, the demands on Black labor by capital have brought about momentous shifts in U.S. culture and policy, the economic power of the US elite, and the autonomy of Black Americans.

To provide the ideological legitimacy needed to sustain such a system, Baron displays how a culture of control fermented within U.S. and beyond. This cultural system was fostered by white elites to both maintain dominance over enslaved Africans and to keep the white population that did not hold slaves from rebelling against a system they could not control. Unique to the United States, compared to other places within the Americas, was the creation of “rationale regarding the degradation of all blacks”, which Baron argues was vital for the continued enslavement of “some” of the US Black population. For Baron, these attributes of Black chattel slavery set it apart from other forms of slavery and indeed constituted a “new type of social formation,” entirely.

Shifts in the demand for Black labor during slavery brought about a more “self-contained operation” as capitalism matured and the international slave trade slowed. Baron notes that after Independence from Britain, cotton came to dominate the aims of the southern planter class and slave owners in the Upper North were more than willing to sell their slaves southward given their increased value as new imports of Africans were nearly halted. The North supported slavery as well, by sponsoring European immigration despite the presence of Black workers and the enforcement of federal slave laws.

According to Baron, the position of the “quasi-free Negro” provides readers with vital insight for future transformations in the demand for Black labor. Still victims of a vicious anti-black society, non-slave Blacks were subject to many of the same systems of control that the enslaved were, albeit from a different position. These oppressions combined to restrict Black people from securing a stable position within society. Just before the Civil War, Baron notes that around 89% of Black people were enslaved within the US. Thus, quasi-free Negroes had their position “ascribed from that of the mass of their brothers in bondage.” According to Baron, as economic competition increased in urban areas with the maturation of capitalism, many non-slave Blacks lost what skilled positions they had and left large cities altogether.

Baron concludes the section on the slave period by stating simply that there was not a significant demand for non-slave Black labor. The theft of Black labor within the South that took place outside of the plantation system simply augmented the system of slavery to fit the desired setting. Furthermore, the racist, anti-black logic that produced these oppressions would carry over within American culture and politics long after slavery ended with the defeat of the Confederacy and their gradual federal re-integration that followed.

The Reconstruction era, which heralded massive advances in the lives of formerly enslaved Africans (now US citizens), was short-lived and its conclusion ushered the white Southern elites back into power after their defeat during the Civil War. With this power, they once again sought to maintain control over Black labor through political pressure and outright physical violence. The agrarian system that was established in the post-Reconstruction South created a class of Black workers that had less power and autonomy than any group of white workers, whom they came into increasing competition with during this period. According to Baron, the “abolition of slavery did not mean substantive freedom to the black worker”, which was demonstrated by the fact in both eras the Black peasantry only received only enough to subsist on. This low position, combined with a viciously anti-black American culture, created conditions in which the Black worker was increasingly tied to the bottom rungs of the white-controlled US agrarian economy.

The increasing competition between Black and White workers during post-Reconstruction era brought about several important shifts for the demand for Black labor. Much of this competition was centered on land rivalries, with emancipated Black families seeking to secure land having to confront an overtly racist system of Southern politics. With the increasing numbers of poor white farmers in the south, the Southern political elite sought to further cement their hegemonic control over both Black and White workers through shoring up gaps within their “color-caste distinctions”. Baron also notes that massive shifts were also taking place within the Southern ruling class, which saw much land trade hands away from former slave masters into the possession of merchants and lawyers. This transformation saw decision-making amongst the Southern elite shift from a more paternalistic approach to “land-owners’ making their decisions more nakedly, on the basis of pure entrepreneurial calculations.” In such a position, Black workers faced oppression from both the Southern elites’ decision making and the competition from landless whites.

During the Reconstruction era, the Black workers desire for land was inseparable from their quest for self-sufficiency and autonomy. With the temporary defeat of this quest by the forces that conspired to end Reconstruction, this momentum faced a massive setback. While movements for Black national liberation wouldn’t renew themselves until more northward migrations brought Black workers into urban centers in higher numbers, the “embryonic nationalism” and quest for racial unity held by these workers were captured in the movements surrounding Booker T. Washington and other smaller “exodus groups” which set up independent Black settlements throughout the lower-Midwest and southwest in particular.

With the oncoming of the World War I, the position of Black workers again faced major transformations. With the precarious relationship between the US and European nations, immigration from Europe was curtailed—opening up sectors of the labor market to Black workers at unprecedented levels. Baron identifies three key developments that arose from these events: First, the outmigration of millions of African Americans from the South to urban centers in the North; Second, the development of a Black proletariat in these urban centers; and third, the shift away from tenancy farming in the South. According to Baron, while World War I started many of these societal shifts, “World War II was to repeat the process in a magnified form and to place the stamp of irreversibility upon it”.

In these urban centers, Black workers remained more vulnerable to unemployment and the racist white working class, with help from city and state institutions, carried out violent campaigns of “race riots” throughout urban Black communities in the North. Often, white management would utilize the inclusion of Black workers to divide the work force—causing white workers to draw focus away from inter-class conflicts to confront the Black worker menace they were becoming more confronted with. Furthermore, Black workers were nearly always kept from skilled positions or managements positions. These issues were exacerbated by the tactic of white company owners attracting the subservience of a Black managerial class, made up of Republican anti-union “leaders”, to gain influence in the Black community. In the south, Black workers had little opportunities in southern Industries like mining & lumber, and remain largely restricted to agrarian work throughout the inter-war period.

By the 1970’s, only one-fifth of Black people lived in the South, and the percentage of Black agrarian workers fell to 4% of the Black labor force. The increasing urbanization of Black people brought, among other things, massive changes for the superstructure of racism within the US. For Baron, “it meant the disappearance of the economic foundation on which the elaborate superstructure of legal Jim Crow and segregation had originally been erected.” As monopoly state capitalism matures, economic shifts have caused Black workers in the US, like “non-citizens” from Southern Europe and Northern Africa that fill up the gaps of Western Europe’s labor market, to maintain a marginal status due to their race.

According to Baron, the endemic subordinate status of Black workers amounted to a “system analogous to colonial forms of rule”. Unmoved by the potency of Civil Rights Era protest to alter the demand for Black labor, Baron suggests that the racist institutions of this country can only be altered by a “earthquake in the heartland.” Unable to de-colonize the Black community due to its attachment with major urban centers, the American capitalist relies on the hegemonic control of Black labor to retain its hegemonic position.