Synopsis by Chelsea Birchmier

“An Equal Chance for Education” is a policy report for the Chicago Urban League (CUL) prepared by Harold Baron in March of 1962. The report was written as a guide for individuals and organizations concerned with children’s educational quality and equality. Baron aimed to provide a basis for understanding school segregation that would inform action, writing, “comprehension is a prerequisite to effective action.” He argued that the schools were obligated to use every possible resource to provide equal educational opportunity for children, and that when segregation, both in schools and in housing, prevented such equal opportunity, schools had the responsibility to compensate for those conditions.

Baron traces the segregation in U.S. schools to slavery, when slave states forbade Black education, followed by a Jim Crow pattern of segregation until the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, after which legal, or de jure, segregation began to decrease. However, extralegal, or de facto, school segregation continued in Northern cities via residential segregation and other policies supported by boards of education and school administrators, resulting in little difference between Northern and Southern states regarding the actual experience of segregation. This pattern of de facto segregation was evident in Chicago as of 1960, where only 10 percent of Black elementary school students attended integrated schools. Two major cases challenged the legality of segregation: the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case, which established that de jureschool segregation was unconstitutional, overturning the “separate but equal” standard established by the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case and the 1961 Taylor v. New Rochelle Board of Education case, which established that de facto school segregation via gerrymandering and intentionally drawing school boundaries so as to contain Black residents was unconstitutional. The New Rochelle case, however, did not establish a positive policy of integration that would require school boards to actively promote integration. Despite the New Rochelle case and Illinois laws that had forbidden student assignment to schools by race since 1874, de facto segregation continued in Chicago schools. According to Baron, the distinction between de jure and de facto segregation made little difference when it came to its effects on children.

Baron details some of the psychological and educational effects of segregation. He points to research showing the feelings of inferiority and motivation for education that Black children experienced due to segregation, which reinforced their acceptance of second-class status. Segregation also had harmful impacts on white children, teaching them values that conflicted with moral, religious, and democratic principles, as they absorbed ideas of superiority. Black children were often “doubly handicapped” by socioeconomic status. The handicaps faced by Black and low-income families were compounded by educational practices, which provided them materials and tests based on white middle class experiences and values and denied them out-of-school experiences and high quality educational resources. This mandated that equal educational opportunity could only be achieved if “the schools compensate for the inequities perpetrated by our society.” The educational system then served to reproduce race and class differences and to contribute to an intergenerational cycle in which Black job seekers moved from a discriminatory educational system into a discriminatory labor market, to then raise children who would enter a segregated school.

Baron then examines the history of segregation and integration in Chicago schools from the 1860s onward, revealing a pattern of segregation followed by community protests challenging segregation. In 1863, an Illinois ordinance required that Black and white children attend separate schools. A sit-in campaign was organized in which Black parents continued sending their children to the nearest school despite the ordinance, and Black residents occupied the Board of Education’s and the mayor’s offices; in 1865, the ordinance was repealed. At this time, the South Side community was just beginning to form. It wasn’t until the Great Migration during World War I that the South Side community expanded, as Chicago’s Black population doubled from 1920 to 1930. During this time, the Black Ghetto was formed by practices of the Chicago Real Estate Board and restrictive covenants, agreements between property owners to not sell or rent homes to Black residents. By 1940, primarily Black schools became overcrowded and increasingly operated as double-shift schools, in which one group of children came to school during a morning shift and another during an afternoon shift, reducing the amount of time Black children spent in school, while white schools began to accrue underutilized space. The Chicago Board of Education maintained these conditions by implementing a neighborhood school policy and freezing school boundaries at the Ghetto, allowing white but not Black children to transfer to underused white schools, districting Black elementary school graduates into Black high schools, decreeing neutral areas, and spending less on Black schools. In response, the Black community again organized protests, alongside The Citizens Schools Committee, The Better Schools Committee and the Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs. Their protests ultimately helped to oust the corrupt regime of Board of Education President James McCahey and Superintendent of Schools William Johnson, who were investigated by the National Educational Association and accused of collaborating with the Chicago Real Estate Board in creating poor conditions for Black students. There was some improvement when Herold Hunt replaced Johnson as Superintendent in 1947. With the help of a committee led by Professor Louis Wirth at the University of Chicago, elementary school boundaries were shifted to help with overcrowding and many neutral areas were removed. However, this plan operated on a colorblind principle and altered boundaries without taking into account race. According to Baron, programs had to become “positively ‘color-conscious’” instead of colorblind to bring about significant change. Hunt was succeeded Benjamin C. Willis in 1953, who did not continue with the plans of the committee to address unequal high school usage.

After detailing this history, Baron locates the continued existence of residential segregation and Ghettoes as a major social factor affecting de facto school segregation in Chicago. Residential segregation remained consistent despite the increase of Chicago’s Black population from 492,000 to 813,000 from 1950 to 1960. Ghettoes helped to maintain segregated, overcrowded Black schools via neighborhood school policies in the South and West sides of Chicago. In turn, school segregation also served to maintain housing segregation, such that white families began to move out as soon as Black children entered a school in the area. After 1953, segregation increased as the Black school population grew, such that, by 1961, 90% of Black elementary school students attended all-Black schools. The Board of Education’s school building program placed new schools according to the neighborhood school policy, building more segregated schools and only shifting boundaries within the Ghetto. The educational facilities continued to be unequal, with Black schools overcrowding and students on double-shift, facing a lack of lunch rooms or even library rooms and textbooks in contrast to white schools with underutilized rooms, and unequal assignment of teaching personnel and expenditure per pupil. While less pronounced in high school, segregation along with diluted curricula in mostly Black schools continued, particularly in vocational and trade schools. These conditions negatively impacted the academic performance, dropout rates, and test scores of Black elementary and high school students.

Baron suggests that the effects of separate and unequal education were cumulative and intergenerational and points to the inadequacy of the policies of the Chicago Board of Education in addressing the conditions producing such effects. Neither their school building program nor Superintendent Willis’ plan relieved overcrowding or double shifts in Black schools. Schools instead attempted to reduce overcrowding while maintaining neighborhood boundaries by creating mobile classrooms outside schools in the Ghetto, placing children in classrooms without teachers, and using floating classrooms that roamed the hallways looking for an open room. From 1957, public protests and pressure from Black residents, PTAs, the Urban League, NAACP, and the Citizen Schools Committee challenged these conditions. In 1960, parents at Gregory School picketed the Board of Education and organized a campaign called “Operation Transfer” with the NAACP, attempted to enroll students in overcrowded schools into white schools, and filed a lawsuit in the Federal Courts. With public hearings of the Board of Education in 1961, protests increased. Parents of children at Burnside School and Parker Elementary adopted sit-in tactics from the Civil Rights Movement, and parents in the South Side went on strike in response to an attempt to make an old dangerous building a mobile classroom. Baron writes that schools had become a “focal point” in the struggle for equality in Chicago, and that if the Board continued its inaction, Chicago might become known as “a Little Rock on Lake Michigan.”

Baron then provides examples of integration programs that Chicago should aspire to, such as New York City. After a study of the status of public education for Black and Puerto Rican children in New York City found patterns of separate and unequal education, school boundaries were rezoned to create integrated schools. Open Enrollment policies allowed children from overcrowded schools to attend schools with underused facilities out of district, and the Board covered transportation costs. A strong human relations program and training ensured buy-in from stakeholders so that the program was implemented smoothly. Special programs such as the Demonstration Guidance Project were designed to compensate for children who were behind in studies and provided remedial reading, extra counseling, as well as out-of-classroom experiences, resulting in major increases in reading level, academic performance, and school attendance. He mentions several other programs in various cities that attempted to address separate and unequal education, such as the St. Louis Banneker Project, which combined motivational counseling with students and parents and remedial summer reading, resulting in increases in reading and math performance.

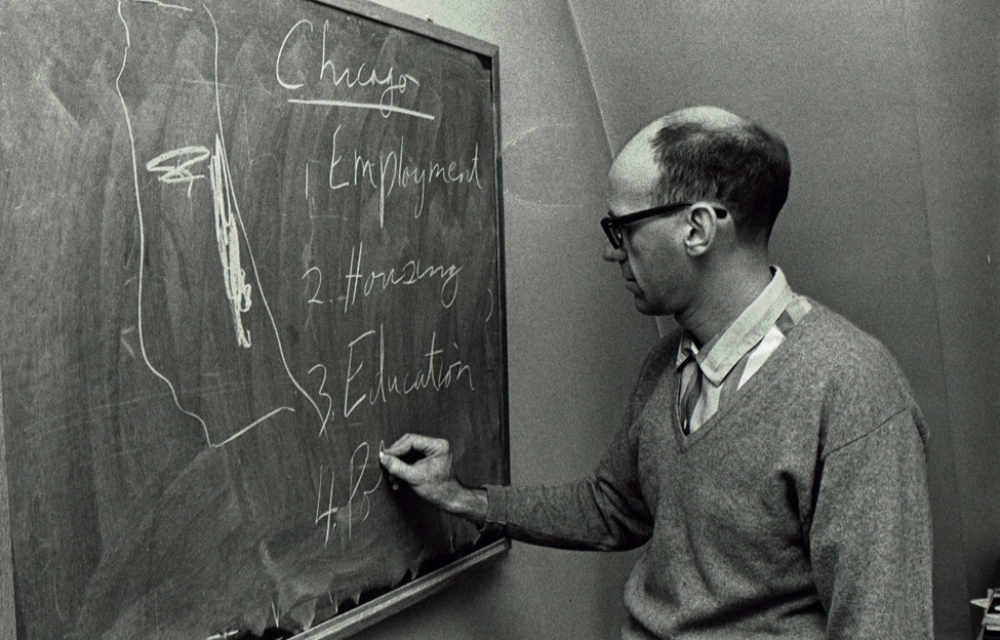

Baron concludes by considering what Chicago could do. First, he makes it clear that nothing would change without participation and pressure from the community. Next, he argues that the Board of Education had to adopt and implement a strong policy and program of integration and for quality and equality of education, The first step for the Board in developing such a policy would be a survey of public schools, advised by a citizen’s advisory community representing major groups in Chicago. Additionally, boundaries had to be redrawn to promote integration, transportation had to be provided for children from overcrowded schools to attend underutilized schools, personnel had to be integrated, educational quality and standards had to improve with no watering down of curricula, and psychological and social work services had to be offered. Extra facilities and programs also had to be provided to children who had been disadvantaged by the educational system. A strong human relations program would be necessary to ensure the implementation of the policy. For Baron, the realization of such a program was only a first step toward democratic education; once those reforms were adopted, Baron writes, “the efforts of many others can be called upon to support a real educational crusade for democracy.”