Synopsis by: Chelsea Birchmier

Part I

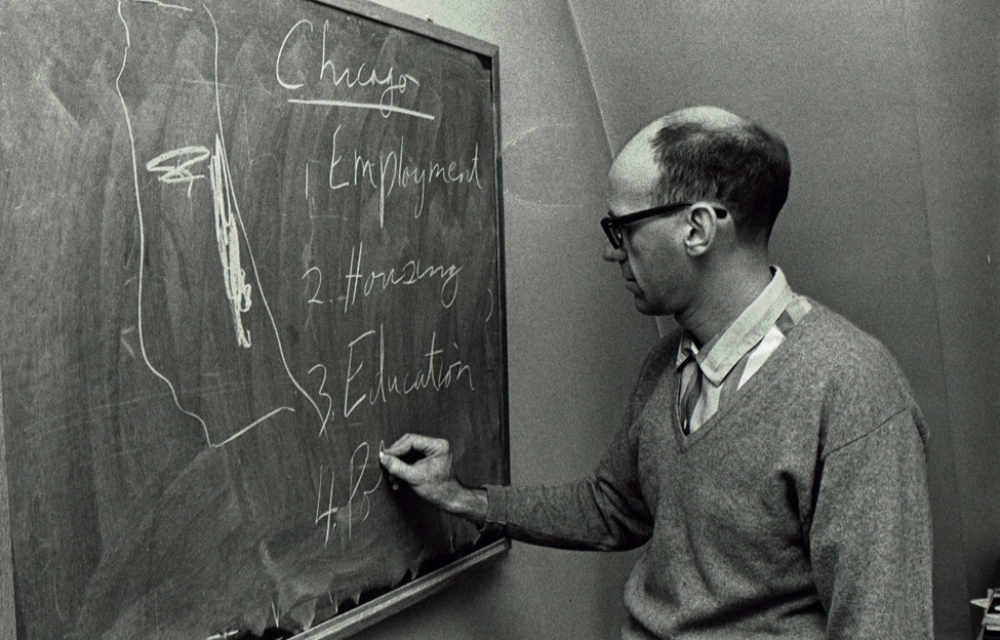

The four years leading up to 1965 were marked by prosperity, according to the President’s Council of Economic Advisers. Yet, as Baron and Hymer point out, this prosperity did not extend to Black workers, who, quoting Martin Luther King Jr., constituted “an island of poverty in a sea of affluence.” They demonstrate this paradox of prosperity spatially by contrasting employment and housing conditions in the Northwestern suburbs, where most of the jobs were located, and the unemployment and public housing projects, which Baron and Hymer refer to as “apartheid [that was] almost complete” and “the largest single concrete reservation for a dispossessed urban peasantry” in Chicago’s South and West Sides. The condition of Black workers in Chicago, write Baron and Hymer, was reflective of the experience of Black workers in the urban North. In part I of this paper, Baron and Hymer demonstrate the “second-class status of the Negro worker” by examining racial differences between Black and white workers in four areas: labor market participation, unemployment, income, and occupation. Generally, the gaps in these areas were more marked for men than for women, which they explain as a result of all women experiencing job discrimination and Black women obtaining jobs more easily than Black men.

Unemployment estimates did not include those who were not actively seeking employment. For this reason, in his 1963 paper “Negro Unemployment: A Case Study,” Baron developed a “social concept of unemployment” that incorporated the “discouraged workers” who had given up on the job search. Nationally, while the Civil Rights Movement helped maintain labor market participation rates for Black men ages 20 to 34 years old, they declined for Black men over 34 and teenagers; rates decreased by one-sixth for Black male teenagers from 1960 to 1965 and only one-sixteenth for white male teenagers. While Black female teenagers had lower participation rates than white female teenagers, Black female participation for 25-to-44-year-olds was greater than white female participation, likely due to white women leaving the market to raise families.

Baron and Hymer point to systematic differences in employment between white and Black workers. Nationally, from 1950 to 1965, unemployment rates rose for all races, with nonwhite unemployment consistently greater and longer in duration than white employment. In Chicago, the nonwhite to white unemployment ratio was higher than the national ratio, with Black unemployment three times white unemployment for all three measures of unemployment from 1959 to 1961. Even in the tight Chicago labor market of 1965 with white unemployment at only 2 percent, nonwhite unemployment had only decreased to 6 to 7 percent, but this decrease was a result of more Black workers leaving the labor force as discouraged workers. Baron and Hymer cite Lester Thurow’s 1965 study to demonstrate that nonwhite employment went through greater fluctuations than white employment, with nonwhite workers being absorbed into and cast out of the labor market in economic upturn and downturn, respectively, at greater rates than white workers. Ultimately, Baron and Hymer viewed disparities in employment as primarily structural rather than skill-based or educational, as evidenced by Denis F. Johnston’s 1965 paper showing that a nonwhite worker with a high school education was no more likely to be employed than a white worker who had not completed eighth grade.

They then discuss income, which increased for all races between 1940 and 1965. Yet, the relative gap between Black and white incomes never closed, despite temporary improvements in relative Black wages in wartime tight labor markets. According to Baron and Hymer, the fact that Black male income was 41 percent of white male income in 1939 was reflective of regional differences between a rural Southern labor force and an urban Northern labor force. The relative income of Black men increased to 54 percent of that of white men in 1947 with the redistribution of Black labor to the urban North, but the gap had not narrowed by 1962, largely reflecting racial differences within cities as opposed to the former regional differences. Next, they compared personal income data by race in Chicago in 1949 and 1959 broken down by upper, middle, and lower income quartiles. The largest gap in 1949 was in the upper quartile, with Black men earning 68.3% of white men’s income. By 1959, in a reversal of the earlier trend, the relative income of Black men decreased substantially for the lower income quartile to only 60.8% of white men’s income. The quartile data pointed to emergent Black class stratification, with the income of the bottom quartile decreasing relative to the top quartile from 1949 to 1959 and the lower income earners constituting “an urban peasantry, living at a subsistence income, and clearly out of the main stream of the economy.” Baron and Hymer also show how the racial gap increased for Black men with age, suggesting greater opportunities for promotions and job security. Black female income did improve relative to white female income from 1949 to 1959 in the lower and median quartiles and remained constant in the upper quartile, but this might have been due to the growing number of white women working part-time jobs, and thus, earning smaller incomes. However, their analysis suggests that the gap in income between Black and white female heads of household was similar to the gap between Black and white men. As with employment, racial differences in income were systematic and could not be explained by differences in education; in fact, Black male college graduates earned less than white dropouts.

Finally, Baron and Hymer describe the occupational second-class status of the Black worker, who was concentrated in the occupations that were at highest risk of automation. As with income, while both Black and white workers had moved into more skilled and higher paying occupations in absolute terms, Black workers had not improved occupationally relative to white workers. In the city of Chicago, Black workers were concentrated in the unskilled and semi-skilled occupations while excluded from the professional, technical, and managerial jobs. Baron and Hymer constructed an occupational index to demonstrate the relation of Black workers to white workers within the occupational structure of Chicago. The closer the index value to 100, the greater the proportion of Black workers in higher paying, more skilled jobs relative to white workers. They found that between 1910 and 1950, the index ranged from 82 to 85 for both Black men and women, except for a drop in Black women’s occupational index in 1940 during the Great Depression. In the Chicago Metropolitan Area, Black men’s occupational index value dropped from 83 in 1950 to 77 in 1960, partly resulting from a greater proportion of white men entering professional and managerial occupations. Black women’s index increased from 83 to 87, likely due to an increasing proportion of Black women entering clerical jobs. The occupational index did not measure divisions within occupations; even within the higher paying occupations in Chicago, Black workers were earning substantially less than white workers, particularly in sales, managerial, or proprietor jobs. The smaller gap in occupations including operative, service workers, and laborers was potentially a result of minimum wage laws and union coverage, with a larger gap among craftsmen jobs, where trade unions often excluded Black workers.

Part II

After offering evidence for the second-class status of Black workers, Baron and Hymer go on to analyze its dynamics in Part II of this chapter. The racial disparities in labor force participation, employment, income, occupation, they write, were “permanent features of the Chicago labor market since World War I.” In contrast to white immigrants, for whom disparities dissipated after a generation or two, Black workers in Chicago, an increasing proportion of whom were born and raised in Chicago, were permanently concentrated into certain sectors of the labor market like they were into segregated schools and ghettos. Baron and Hymer first describe the racist ideologies that explained this second-class status and how they emerged as justification for existing conditions. Southern myths involved the biological and genetic inferiority of Blacks as justification for slavery and later peonage, as evidenced by writings from John C. Calhoun and James De Bow. With the mass migration of Black workers to the North after the 1920s, new ideologies developed to justify Northern racial institutions that attributed the conditions of Black people to individual and psychological deficits and racism to prejudices and preferences. Then, they furnish their own analysis in contrast to these myths and offer three generalizations to understand how the Chicago labor market drove the disparities discussed in Part I: a dual labor market with separate Black and white sectors, a surplus labor pool that included an unemployed and marginally employed labor force used to supply labor during shortages, and a complex Northern system of de facto segregation where racial barriers in one institutional area supported those in other areas. Finally, they describe how ideologies of racism and a lack of political power upheld these dynamics.

Baron and Hymer examine the dynamics of the racially dual labor market, where a primary labor market in which white workers are recruited and seek jobs exists alongside a smaller sector in which Black workers are recruited and seek jobs, each sector operating on separate supply and demand forces, with jobs transferred to the Black sector with the growth of the economy and the Black labor force. They then begin to explain the mechanisms through which jobs were distributed to white and Black workers. Black workers were segregated by industry as well as smaller units within an industry. In Chicago industries, Black workers were employed in government and primary metal industry jobs in much higher proportions than white workers, while the reverse was true in the banking and finance and non-electrical machinery industries. This trend intensified when looking at firms within an industry. Baron and Hymer present data from the Chicago Association of Commerce and Industry that showed the proportion of firms that were segregated in 1964, meaning they did not hire nonwhite workers. Seven of ten small firms, one of five medium-sized firms, and one of thirteen large firms were segregated. Within firms, further segregation occurred by occupational classification; most professional, managerial, sales, and skilled craftsmen classifications excluded nonwhite workers. When these occupational classifications were not segregated, the departments within them often were, with Black workers often in “hot, dirty departments” like foundries. Generally, they write, the lower positions in the occupational hierarchy were more likely to be integrated. An exception was found in the increased employment of Black women as clerical workers. While less marked, racial divisions also existed within government jobs, where many skilled Black workers found employment due to decreased hiring barriers. While 19 percent of US Government employees in Chicago’s Civil Service Region were Black, 27 percent at the lower level and only 1.7 percent at the higher level were Black. In another example, the Chicago Board of Education, the largest employer of Black professionals, the majority of Black employees taught and served as administrators for primarily Black schools. Segregated hiring patterns led to separate job-seeking patterns, with Black workers looking for jobs in the Black labor market and white workers in the White labor market. The recruiting practices of firms, the referral practices of employment agencies, and the guidance of schools and counselors reinforced racial dualism in the labor market.

Baron and Hymer then argue that the Black labor force consisted of three components: a Black service sector, which primarily supplied services to the Black community, a standard sector, which supplied services and goods across communities, and a surplus pool of labor that was either unemployed, out of the labor force, or marginally employed. They estimated that about 50 percent of the Black labor force was employed in the standard sector, 10 percent in the Black service sector, and 40 percent in the surplus labor pool. The workers who were marginally employed in the surplus labor pool worked in low-paying, dirty, and unsafe jobs that were often temporary with few possibilities for advancement, including jobs that were given to Black workers as white workers climbed the occupational ladder and those that had become “traditional Negro jobs” like bootblacks, busboys, and servants. The level of subsistence income for workers in the surplus sector was primarily determined by welfare payments, and in Chicago, one-fourth of Blacks received public assistance. Additionally, the size of the pool depended on the level of unemployment in the economy at large and the level of white immigration. They suggest that movement out of the surplus labor pool occurred during period of economic expansion, which had facilitated Black workers moving out of the surplus sector from 1940 to 1965; however, the ongoing expansion of the Black labor force, particularly though teenagers entering the labor market as well as migration from the South, meant that the tight labor market was not enough to reduce the surplus labor pool. They make a comparison to studies of underdeveloped countries in which there a technologically advanced and industrialized sector existed along with a subsistence peasant sector with high marginal and unemployment. Similarly, they write, the labor market in the U.S. was divided into a skilled technologically advanced sector made up of white workers and an “urban peasantry” in unskilled and marginal jobs. During labor shortages, Black workers were brought into the general economy without raising wages, they suggest, because they were previously earning subsistence incomes. Baron and Hymer offer racial dualism and the surplus labor pool as explanations for why unemployment rates in the U.S. were greater than workers in Western Europe would accept; the increased rate of Black unemployment helped keep white unemployment down. However, they suggest, the Civil Rights Movement had the potential to make a high Black unemployment rate unacceptable.

According to Baron and Hymer, the disparities in the labor market were reinforced by racial institutions in other areas including the de facto barriers of housing, schooling, and employment discrimination that were not mandated by law but operated as though they were. These institutions formed a self-perpetuating network that was more than the sum of its parts such that barriers were mutually reinforcing, and reducing barriers in a single area had little effect without transformation in others. Employment discrimination occurred in various forms, including screening based on criteria that was direct (e.g., race) or indirect (e.g., residence near the job), cultural biases, lack of advertisements and recruiting in Black media, and exclusion from trade unions (while the industrial unions were often less discriminatory). Housing segregation was evident in Chicago, as was demonstrated by Chicago Urban League maps from 1950, 1960, and 1964, showing an expansion of Black ghettos on the South and West sides of Chicago, following historical block-by-block segregation patterns. Housing segregation confined Black workers geographically so that they were unable to access jobs, which were rapidly moving away from the Black ghettos of Chicago and into the Northwest from 1957 to 1963. School segregation had impacts on the skills and training of Black workers, with Black students concentrated in schools of inferior quality and faced with low expectations. Baron and Hymer quote social psychologist Kenneth Clark, who said, “Personnel managers need no longer exercise prejudicial decisions in job placement; the educational system in Chicago screens Negroes for them.” These barriers were supported by racist ideology and a lack of political power. White decision-makers from the suburbs were making decisions about Black employment, education, and housing. Black workers controlled few major institutions, owned few companies and held no wealth. They reference James Q. Wilson, who writes that the Black democratic organization, while it was able to mobilize voters, was secondary in power to the Cook County Democratic Party and did not hold power proportionate to these votes. The Civil Rights Movement was filling that vacuum of political power by using mass participation to influence decision-makers. It was yet to be seen whether the Civil Rights Movement would be able to transform the network of de facto barriers, but Baron and Hymer noted that they were working to redistribute employment and improve education and housing.

Finally, Baron and Hymer conclude that the dual labor market was a structural phenomenon that necessitated a transformation of social and economic institutions. The implications of this were that transformation had to occur on both the demand side, by removing hiring discrimination, and the supply side, by addressing school and housing segregation, that programming had to be built under the assumption of racial dualism in the labor market, and that the disparities would continue if the market was expected to check them and the network of racial institutions continued to support them. Long-term changes had to be made at all levels, including employers, unions, agencies, and the government to deconstruct the dual structure. The Civil Rights Movement had primarily impacted discriminatory hiring barriers, rather than housing and school segregation, and led to new laws and Federal Executive orders to this end. Firms contracted by the U.S. government became subject to the President’s Equal Employment Opportunity Program, and some Black workers were employed in professional and managerial jobs. These changes were mostly symbolic, however, and no major structural transformations had occurred. These minimal changes were summarized in a comment from an observer that “in the past personnel men used to discriminate against 9 out of 10 Negro applicants; today they only discriminate against 8 out of 10.”