Synopsis by: Briana Gipson

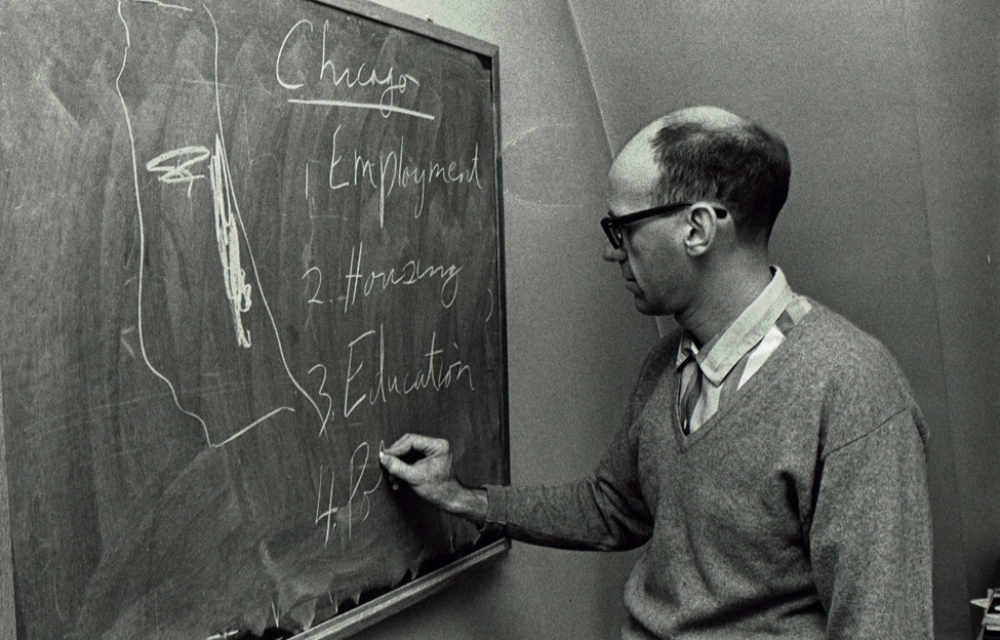

In 1967, Hal Baron delivered “Public Housing, Chicago Builds a Ghetto” as a fiery, anti-colonial speech on the state of Chicago’s public housing system. This speech was delivered to an audience containing Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) leaders and staff at a symposium at the University of Chicago on March 10, 1967. He would use his speech to critique the City of Chicago’s and the CHA’s practices and reveal the negative outcomes they created and forced on Chicago’s Black community. He argued that City transformed its public housing system into a tool that implements and solidifies racism. It essentially became a system that segregated Blacks, decreased their mobility, and altered their community networks and solidarity by social, economic, and political force. He devoted his speech to discussing the federal government’s, Chicago’s and CHA’s role in creating ghettos, or areas with high concentrations of low-income Blacks, through public housing. He organized his discussion into four separate sections.

The first section of Baron’s speech is titled “From Crusade to Containment”. He began this section by discussing the three major periods of public housing from the lens of the Chicago Urban League. His main point is public housing was originally organized as a campaign to rid problems associated with urban life such as overcrowding and poverty by the federal government. Then it became a system to support World War II war workers before finally becoming “a virtually Negro institution” Baron says. In other words, Baron claimed that it became a system designed to reinforce the racial biases of those in power. He used CHA statistics to show that their biases resulted in Chicago’s public housing system being 90% Black, in 90% of CHA’s properties. Baron explained how Jim Crow and anti-black legislation in the League’s three public housing periods led to Chicago’s segregated and predominantly Black public housing system in the 1960s.

The next section of Baron’s speech focuses on the influence of federal policies and urban renewal on Chicago’s segregated and Black public housing system. The name of this section is “The Safety Valve for Urban Renewal”. It fundamentally argued that Chicago’s public housing system became segregated and Black because it used its system as a “safety-net” for urban renewal. Baron unpacks this argument by revealing how the federal government’s housing and transportation policies began altering housing supply based on race beginning in the late 1930s. It offered Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and Veteran Affairs loans to Whites, which contributed to mass suburbanization processes and ultimately increased Whites’ housing supply. Baron indicated that suburbanization expanded at the expense of Black neighborhoods as the federal government subsidized expressways to support migrating Whites. These expressways along with urban renewal would displace thousands of Blacks and decrease their already limited housing supply. Baron asserted that this led to Chicago’s public housing properties becoming relocation settlements or “catch-basins” for Blacks who were uprooted from their homes and livelihoods. He provided evidence showing that CHA transitioned from serving mostly low-income, White neighborhoods prior to 1949 to proposing over 95% of its properties in Black neighborhoods from 1950 to 1955. Baron further supported his main argument that Chicago built a segregated and concentrated low-income Black community by ending this section discussing how the CHA came under fire for proposing a housing project development in a White neighborhood. His example showed how firm the City of Chicago was in creating and maintaining segregation through the CHA.

Baron’s third section describes how CHA began to engage in disparate treatment once its public housing system became predominantly Black. He particularly focused on the CHA’s building designs. He explained that CHA’s building designs followed the Garden City movement when it was created for Whites and war-workers. They were often constructed as single family apartments with green space. However, once CHA began building public housing developments for displaced Blacks, Baron witnessed CHA build dense, high-rise buildings that had larger building coverage ratios. He contended that this building design exacerbated Chicago’s spatial segregation. He supported his claim by explaining that this increased residential segregation within central Chicago strengthened school segregation and furthered separated Blacks from jobs. Jobs were often moving to the periphery of cities as a result of expressway and highway construction, which increased employment segregation. Baron ended this section explaining the negative impact of CHA’s high-rise developments on community networks. He mentioned that it does not allow for Blacks to rebuild the institutions they lost in urban renewal to full capacity. It also weakened community connections and leadership opportunities. Baron’s last sentences showcased that Chicago’s public housing system did not even provide the stability needed for Blacks to rebuild and connect. Blacks lost their public housing vouchers once they made it to a certain income, and Baron foreshadows that this only perpetuates the very racism that led Blacks to Chicago’s public housing system in the first place.

Baron’s last section, “The Powerlessness of Black Tenants”, uncovered how he believed CHA acted as Black colonizers. He began this section describing two differences between the private and public housing market. The differences were that Blacks lacked the alternatives the private market offered and the power to make political decisions. Baron credited these differences to the CHA’s failure to treat Blacks as their clients and accommodate their needs like the FHA did for its mostly White clients. Additionally, Blacks could not significantly influence the ways the CHA operated because it was a public entity that did not often act in Blacks’ interests. They instead provided top-down orders Baron implied. He proclaimed that this made organizations like the CHA paternalistic colonizers that managed the public housing system like wards instead of providing opportunity. Baron ended this section and his raw speech summarizing the main idea he wanted the audience to grasp: CHA’s public housing system segregates and disrespects Blacks. His final words share that Blacks felt “hopeless, helpless, and totally manipulated” by CHA’s disparate and disrespectful public housing system.