This post describes our recent paper “Acoustic effects of medical, cloth, and transparent face masks on speech signals” in The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. This work was also discussed in The Hearing Journal and presented at the 179th Acoustical Society of America meeting.

Face masks are a critical tool in slowing the spread of COVID-19, but they also make communication more difficult, especially for people with hearing loss. Face masks muffle high-frequency speech sounds and block visual cues. Masks may be especially frustrating for teachers, who will be expected to wear them while teaching in person this fall. Fortunately, not all masks affect sound in the same way, and some masks are better than others. Our research team measured several face masks in the Illinois Augmented Listening Laboratory to find out which are the best for sound transmission, and to see whether amplification technology can help.

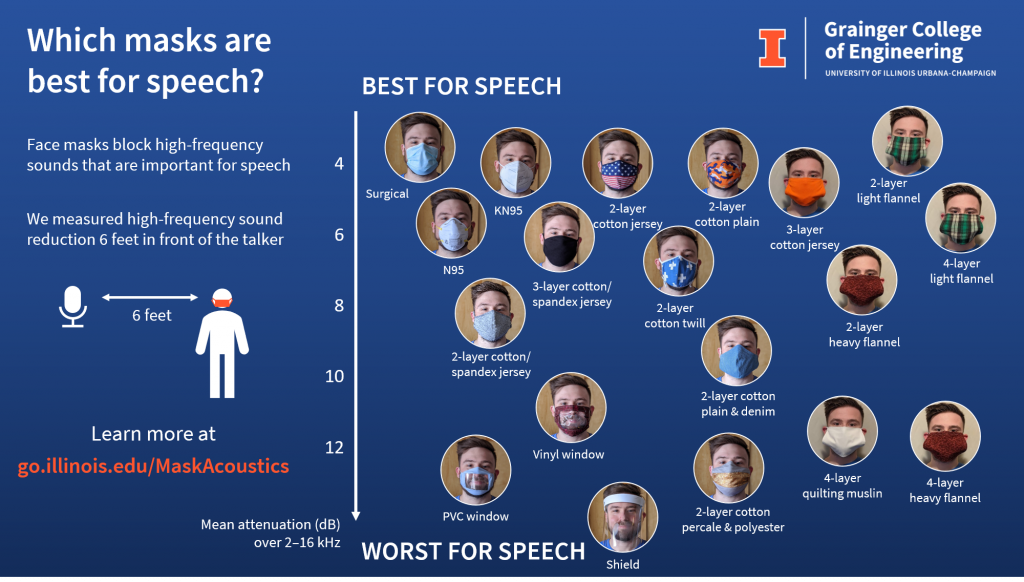

Several months into the pandemic, we now have access to a wide variety of face masks, including disposable medical masks and washable cloth masks in different shapes and fabrics. A recent trend is cloth masks with clear windows, which let listeners see the talker’s lips and facial expressions. In this study, we tested a surgical mask, N95 and KN95 respirators, several types of opaque cloth mask, two cloth masks with clear windows, and a plastic face shield.

We measured the masks in two ways. First, we used a head-shaped loudspeaker designed by recent Industrial Design graduate Uriah Jones to measure sound transmission through the masks. A microphone was placed at head height about six feet away, to simulate a “social-distancing” listener. The loudspeaker was rotated on a turntable to measure the directional effects of the mask. Second, we recorded a human talker wearing each mask, which provides more realistic but less consistent data. The human talker wore extra microphones on his lapel, cheek, forehead, and in front of his mouth to test the effects of masks on sound capture systems.