Happy International Women’s Day!

It all began with the Socialist Party of America orchestrated a Women’s Day on February 28, 1909 in New York. This was received with such enthusiasm and passion that, in 1910, the International Socialist Woman’s Conference insisted this day become an annual tradition.

International Women’s Day is celebrated today in a variety of ways around the world. In some countries, womanhood and relationships are celebrated; in others, the day is used to protest issues relating to women’s rights and equity. But the thing they all have in common? Women around the world are celebrated and deemed worthy of respect and equality, and attention is brought to a number of things that are often overlooked or diminished like women’s suffrage, the gender pay gap, or the rights of a woman over her own body, to name a few.

International Women’s Day, Russia, 1917.

Poster from International Women’s Day, United States, 1975.

Historically, International Women’s Day choses an overarching theme each year to encompass and illustrate a specific area of inequality in need of attention. Highlights from the last decade are as follows:

2018: “Time is Now: Rural and Urban Activists Transforming Women’s Lives”

2017: “Women in the Changing World of Work: Planet 50-50 by 2030”

—A continuation of 2016, this Women’s Day focused on calling for change to include more women in positions of leadership.

2016: “Planet 50-50 by 2030: Step It Up for Gender Equality”

—A frontrunner in 2016, India received International Women’s Day with the opening of four one-stop crisis centers, and celebrated by enabling an Air India flight to be operated by an entirely female flight crew all the way from Delhi to San Francisco.

2015: “Empowering Women, Empowering Humanity: Picture It!”

—This year marked the 20th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action, a historical document that outlines the agenda for discerning women’s rights.

2014: “Equality for Women is Progress for All”

—A memorable moment from this year came from an unexpected source: Beyonce Knowles posted a version of her song “Flawless” overlapping with Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s speech “We Should All Be Feminists”.

2013: “A Promise is a Promise: Time for Action to End Violence Against Women”

—The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) highlighted the extremity of imprisoned women.

2012: “Empower Rural Women — End Hunger and Poverty”

—This year, the ICRC made a call to action to find women who had gone missing during times of armed conflict, underlining the responsibility of parties to search for missing individuals and provide answers to their families.

2011: “Equal Access to Education, Training and Science and Technology: Pathway to Decent Work for Women”

—2011 was a triumphant year for International Women’s Day in some parts. Hillary Clinton launched her “100 Women Initiative: Empowering Women and Girls through International Exchanges”, and President Barack Obama proclaimed March to be “Women’s History Month”. The Red Cross brought attention to the importance of preventing rape and sexual violence around the world, and Australia created a 100th anniversary commemorative 20-cent coin.

—But this year wasn’t entirely progressive. At Tahrir Square in Egypt, swarms of men came out to harass women who were celebrating the day and standing up for their rights, all the while with Egyptian police and military standing by and refusing to take action.

International Women’s Day, Brazil, 2018.

As always with International Women’s Day, it is necessary to remember that, in many countries, not all actions are received openly. Progress made is not always progress kept, and as women’s movements and groups press on, we have to keep in mind that despite what progress we see being made around the world, there are many more unseen obstacles that still need to be addressed.

This year’s theme is “Better the Balance, Better the World”. Trying to create a visual representation of what gender equality looks like, this year’s event showcases a “hands out balance pose” where participants raise their hands in unison to illustrate a balance of equality. Visit the International Women’s Day website to see people taking part in #BalanceforBetter, and remember to celebrate all of the women in your life today, all the while remembering that educating about and advocating for women’s rights is one of the first (and easiest) steps you can take to create a better balanced world.

The march on Washington D.C. fueled by the pussyhat project was accompanied by 600 sisters marches around the United States.

______________________________________________________________

For more information on the theme and events associated with this year’s International Women’s Day, https://www.internationalwomensday.com

______________________________________________________________

Bibliography:

Breneman, Anne, and Rebecca A. Mbuh. Women in the New Millenium: the Global Revolution. Hamilton Books, 2006.

Canadian Women taking Action to Make a Difference!: International Women’s Day — March 8, 2000. Status of Women Canada, 2000.

Choitali, Chatterjee. Celebrating Women: International Women’s Day in Russia and the Soviet Union, 1909-1939. 1995.

Kateri, Akiwenzie-Damm, Rowan Blanchard, Melanie Campbell, Tammy Duckworth, America Ferrera, Roxane Gay, Llana Glazier, Ashley Judd, Valarie Kaur, Cindi Leive, Ai-jen Poo, David Remnick, Yara Shahidi, Jill Soloway, Jose Vargas, and Maxine Waters. Together We Rise: Behind the Scenes at the Protest Heard Round the World. Dey St., 2018.

Kerr, Joanna, Ellen Sprenger, and Alison Symington. The Future of Women’s Rights: Global Visions and Strategies. ZED Books, 2004.

Mijares, Sharon G., Aliaa Rafea, and Nahid Angha. A Force Such as the World has Never Known: Women Creating Change. Inanna Publications and Education Inc., 2013.

Murphy, Padmini, and Clyde Lanford Smith. Women’s Global Health and Human Rights. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, 2010.

Sklar, Kathryn Kish, and Lauren Kryzak. What were the Origins of International Women’s Day, 1886-1920? State University of New York, 2000.

Walter, Lynn. Women’s Rights: A Global View. Greenwood Press, 2001.

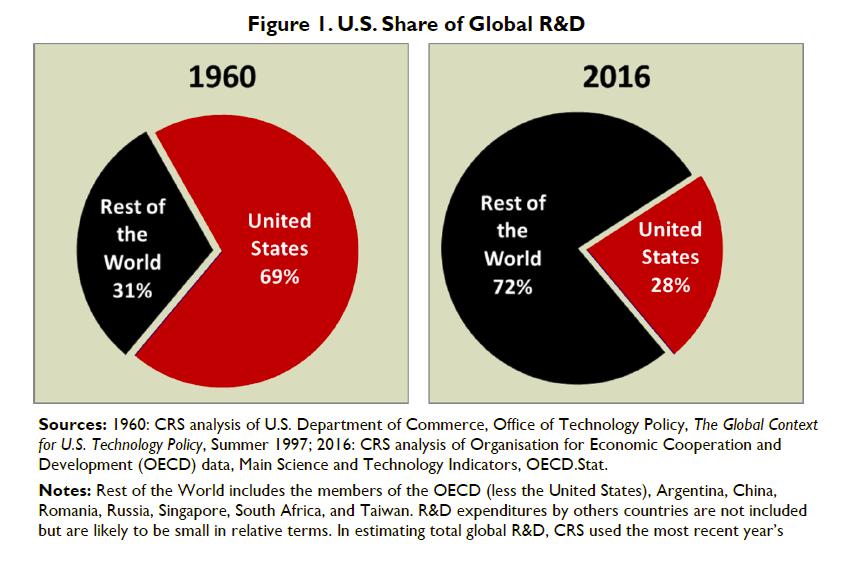

Figure 1: Source: US Congressional Research Service. (2018, June 27). Global Research and Development Expenditures: Fact Sheet. Note the definition of “rest of the world”.

Figure 1: Source: US Congressional Research Service. (2018, June 27). Global Research and Development Expenditures: Fact Sheet. Note the definition of “rest of the world”.