Thaddeus B. Herman – Rapporteur

On Wednesday, September 26, over 30 individuals came together to participate in a discussion on global knowledge and its production. This event was hosted by the Center for Global Studies and was the first in a series of events exploring different aspects of globalization and knowledge. The discussion was led by a panel of four prominent Illinois scholars including Nicholas Burbules – Gutgsell Professor of Education Policy, Organization and Leadership; Andrew Orta – Professor of Anthropology; Assata Zerai – Professor of Sociology and Associate Chancellor for Diversity; and Steve Witt – Director of the Center for Global Studies and the Head of the International and Area Studies Library.

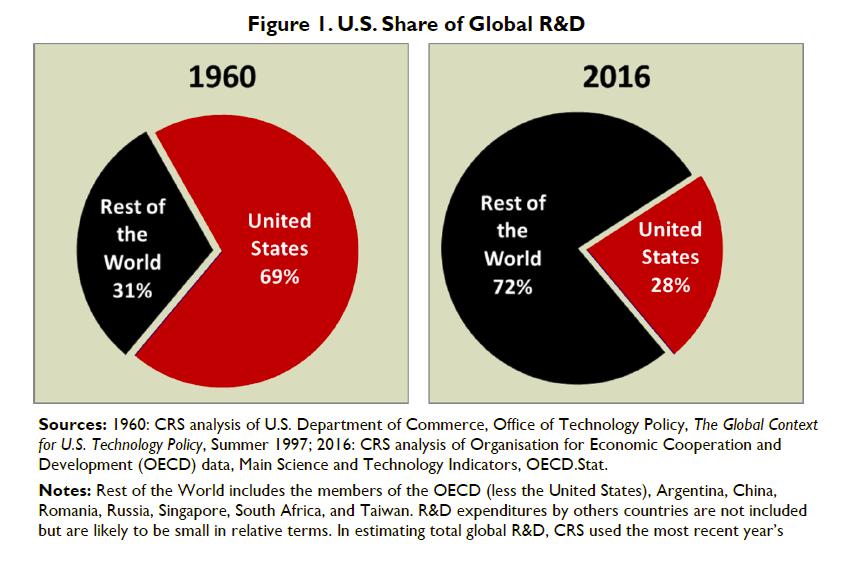

Witt opened up the discussion with a speech on access to academic knowledge and how it is being generated. He showed data that supported his claim that many “global” collections of knowledge really only include a very small portion of the globe and are not representative of truly global knowledge bases. Knowledge production – or at least the knowledge generated that has impact in academic organizations – largely takes place in a few countries, the majority of which are located in regions commonly referred to as the “west”.

Figure 1: Source: US Congressional Research Service. (2018, June 27). Global Research and Development Expenditures: Fact Sheet. Note the definition of “rest of the world”.

Figure 1: Source: US Congressional Research Service. (2018, June 27). Global Research and Development Expenditures: Fact Sheet. Note the definition of “rest of the world”.

Burbules spoke second with a presentation titled “An epistemic crisis”, focusing on many issues around journal publishing. He indicated it is simply not possible to read every new article published in one’s field of study. In fact, more than 80% of all published papers are never cited and those that are cited are often not actually read. He also spoke of the influence of impact factors – the frequency with which articles in a journal have been cited in a particular year – and how this can lead to discrimination against local journals – which may be more relevant to a local population. Research institutions also pressure academics to publish in journals considered to have high impact factors. Of course, this system can be gamed and Burbules included examples of editors of journals who encourage those who submit to cite authors from their own journal in order to increase their impact factor.

Another issue highlighted was the lack of incentive to publish studies which reproduce and reinforce previous studies. Replicability is a cornerstone of the scientific method since a study performed under the same conditions should produce the same results. In fact, when meta-studies have attempted to reproduce results in many areas, a surprising number of results cannot be reproduced – even after increasing sample sizes. So we must ask ourselves the question, how much work of low quality is slipping through and being published?

Andrew Orta spoke on the globalized nature of Catholicism and Capitalism and how they have both been buffeted by local cultural forces. He briefly explored the concept that Catholicism responded to local practices of worship, and adapted to appear more palatable to a local audience. Interesting parallels were drawn between this process, and the process of incorporating global cultural trends into MBA programs around the world. The educational context of the MBA has changed from a “flat” model which saw a fairly standard set of curriculum taught throughout the world to models which are based on various cultural practices found throughout the regions in which the MBA program is established.

The final speaker of the day was Assata Zerai whose talk centered on access and digital inequality. Zerai pointed out that there are excluded voices from multiple fields of study and African research – particularly African research undertaken by women – is not included in western databases that collect research and provide access through search mechanisms. Scholarship that is readily available about Africa is largely generated by western scholars who are often disconnected from actual African perspectives. She argued that there is a direct correlation between the success of people-centered governance structures and women’s access to information and communication technologies (ICT). By not incorporating scholarship undertaken by women on the African continent, we are hindering the promotion of intellectual diversity.

Zerai is undertaking a project to build a database of the works of female African scholars to help make this body of research available to a wider audience and disrupt the conventional division of labor in the social sciences in which African scholars provide the empirical evidence while the heavy lifting of theorizing is left to their western counterparts. The hope is that this effort will amplify the voices of women scholars in African countries.

Following the presentations there was a rich dialogue between members of the audience and the panel members which ended with a dilemma. Can we create systems of knowledge to highlight voices that have been traditionally excluded from processes of knowledge generation and distribution? The speakers acknowledged that there is hope that a way may be found and we can move forward.

For more background information and reading please visit the library guide found at https://guides.library.illinois.edu/cgsbrownbag92618 .

Comments are closed.