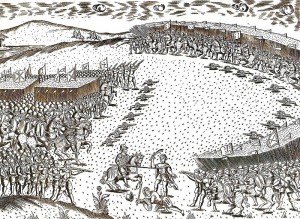

Yesterday we had a rigorous discussion of George Peele’s The Battle of Alcazar, whose meditations on imperial atrocity and the savages amongst us seemed oddly appropriate for Columbus Day. It is a play that seems to gesture to a large network of political problems but seems limited in its ability to contain them fully. We discussed a number of technically compelling moments in the play, including the meeting of the two armies in III.iv and the requirement of a discovery space, the use of human immolation in II.iv, and the the propping up of dead bodies in throughout act five.

In terms of the play’s content, we discussed the primacy of the Moors, wherein the Europeans are invited into the political intrigue but not at the center of its plot. In this way the play seems to operate along parallel dyads, pitting good Catholics against bad while at the same time opposing good Moors against bad. These dichotomies suggest a sliding scale of “blackness,” one whose moral poles could be defined by Shakespeare’s Othello and Aaron as extremes in the noble enemy. Some in the group suggested that the play seems to be a part of a wider stream of thought in the Renaissance that agonized over the inability to diagnose or truly know those around us, ever straining between impulses to demonize or ennoble that which is unfamiliar. Had we thought of it sooner, then, the play might have made an appropriately Halloween-like performance.

* * *

Below are some questions I had prepared for the group that I thought might be useful to those who could not attend:

1) The “presenter” of the play–possibly a Portuguese solider, or Nemesis–begins each act with a brief either moralizing or technologically spectacular dumb show. In these dumb shows, the “modern matter” of the play’s conceit, the Battle and its disruption of geopolitics from the Mediterranean to the Iberian peninsula, is paired with a rhetoric of revenge. This is reinforced by detailed accounts of battle strategy (see IV.i.55-73). Why this ideological pairing? What role are the ghosts and furies meant to play in these dumb shows?

2) How would we discuss the genre of this play? Initially put on by the same company that made The Spanish Tragedy famous, The Lord Strange’s Men of the early 1590s, is this a revenge play set in the Mediterranean? Or is this a Mediterranean play with a penchant for revenge? That the Admiral’s Men were putting the play on nearly a decade later suggests a kind of staying power, certainly. So perhaps the better question would be: what or who, precisely, is being revenged?

3) Like King Lear, the play is suspect of governance that disrupts primogeniture. Here war ensues when brothers who are supposed to take turns at the helm of Morocco can’t stand to share any longer. The mechanisms of valor are constantly at odds with policy-making. So how does the play define good governance? Some moments to consider:

- II.iii.53: “If by valour or by policy”

- II.iii.52: “work affiance,” that is, to create faith or trust

- IV.ii.24-9: Does valor make up for ignorance or impudence?

- Where is “revenge” in this discussion of governanace? It does not seem to be a product of valor, certainly, so is it the possible offspring, the risk one runs, by employing the expediency of “policy”?

4) The play is compelling in part because of the number of extant stage directions (some from a Platt) gesturing to the complex stage technologies required, including the use of human immolation in II.iv. How might we stage the complex specifically in act five? Is some claim being made about the “figurehead” quality of the monarch, the body of the prince “animating troops” (III.iv.60-2) even after death, when they themselves become mere props to morale? Also, consider how one might choreograph the meeting of the two armies in III.iv, which calls for a chariot on the stage.

5) I find Lucy Munro’s piece useful for illustrating what the field has to gain from applying a repertory approach, especially in that she elegantly identifies two major assumptions that hobble many junior scholars: the fragmented composition process, and the influence of industry choices and collaborations on that process. How might this locating the writing of Alcazar “within the authority of the theatre company” inflect out discussion of this play (28)? What “range of agents” seem especially important as part of the “full choir” of meaning for this play (28)? Which less so?