2013 marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of Du côté de chez Swann (Swann’s Way), the first part of Marcel Proust’s lengthy literary masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time, also known as Remembrance of Things Past. The Rare Book & Manuscript Library is celebrating this milestone with an exhibition drawn from its renowned Proust collection. The selection of books and manuscripts follows Marcel Proust through his school-year publications, through the formative years of the study and translations of John Ruskin’s works, to the all-consuming adventure of A la recherche du temps perdu, which occupied the author from 1908 until his death in 1922.

2013 marks the 100th anniversary of the publication of Du côté de chez Swann (Swann’s Way), the first part of Marcel Proust’s lengthy literary masterpiece, In Search of Lost Time, also known as Remembrance of Things Past. The Rare Book & Manuscript Library is celebrating this milestone with an exhibition drawn from its renowned Proust collection. The selection of books and manuscripts follows Marcel Proust through his school-year publications, through the formative years of the study and translations of John Ruskin’s works, to the all-consuming adventure of A la recherche du temps perdu, which occupied the author from 1908 until his death in 1922.

This year also marks the 20th anniversary of the completion of the 21-volume edition of the correspondence of Proust by Philip Kolb (Paris: Plon, 1970-93), a professor of French literature at the University of Illinois whose fifty-year association with the University Library led to the creation of our outstanding collection of books, manuscripts and letters by Marcel Proust. Because Proust never kept a journal, his letters have become the most important source of information about his life and his work. They give us a glimpse of his real-world inspirations and show us how his works subsequently evolved.

In the foreword to the first volume, Kolb wrote:

“The letters of Marcel Proust, if compared to his novel, resemble it to the extent that a tapestry’s reverse side resembles its front. One can distinguish all the threads, all the colors: what is missing is the sharpness in the drawing, the finish, the art, in other words. Likewise, much of what he put into his oeuvre can be seen in his letters, albeit in a less poetic, more genuine light.”

Proust’s talent for writing and his vocation were expressed early on in his letters. He wrote to one of his classmates in 1888: “Forgive my handwriting, my style, my spelling. I don’t dare reread myself. When I write at breakneck speed. I know I shouldn’t. But I have so much to say. It comes pouring out of me.” In 1893, the same year that Proust was editing Le Banquet review with friends, he responded to his father, who was urging him to choose a suitable career path, “I still believe that anything I do outside of literature and philosophy will be just so much time wasted.”

If the years spent on translating and commenting the works of John Ruskin contributed to developing the young author’s aesthetic and critical sense, they didn’t satisfy him completely, as he confided to his friend Antoine Bibesco:

“And this so-called work I’ve taken up again—it plagues me for several reasons. Most of all, because what I’m doing at present is not real work, only documentation, translation, etc. It’s enough to arouse my thirst for creation, without of course slaking it in the least. […] A thousand characters for novels, a thousand ideas urge me to give them body, like the shades in the Odyssey who plead with Ulysses to give them a little blood to drink to bring them back to life and whom the hero brushes aside with his sword.” [December 1902.]

The urge to create, combined with an extraordinary facility for writing, made it difficult for Proust to adhere to the constraints set by his editors and publishers. Writing about an article commissioned by the daily Le Figaro in 1907, he admitted, “they find that I’m always ten times too long, and however much I try to compress, to remove from myself, a bit here and a bit there, Shylock’s pound of flesh in order to weigh less, I can’t seem to arrive at the required length.” The following year, commenting about one of the literary pastiches he was about to publish in the same newspaper, Proust confessed, “I didn’t make a single correction in the Renan. But it came pouring out in such floods that I stuck whole new pages on to the proofs at the last minute.”

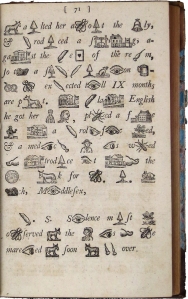

As he embarked on the publication of his novel with Bernard Grasset in 1913, and then with the Nouvelle revue française (NRF) in 1916, Proust continued to employ this work method. The transition from manuscript to type and proofs generated multiple, extensive revisions and redraftings. In April 1913, Proust described his “proof-reading” technique to a friend:

“My corrections up to now (I hope it won’t go on) are not corrections. Scarcely one line in 20 of the original text (replaced of course by another) remains. It’s crossed out and altered in all the white spaces I can find, and I stick additional bits of paper above and below, to the right and to the left, etc.”

A month later, he sent some proofs back to his publisher with this recommendation: “I advise you to draw your people’s attention to the fact that my proofs are very fragile; I’ve stuck bits of paper which could easily tear, and that would cause endless complications. There are galleys which may seem to be half-missing. This is because I have transferred a passage elsewhere.”

The resulting paper mosaics can be seen in two fragments from A l’ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs, on display in the exhibition. For example, a short passage about Odette Swann’s salon, located at the bottom of the 2nd column on the first galley, reappears on the second plate, 2nd column.

The manuscript addition from the first plate was set in type and corrected again. It was then cut out and fixed in the revised textual sequence with much paste and patience by a clerk at the NRF. The resulting text must have undergone at least one additional round of proof-reading because the published version contains minor revisions that are not noted on our fragment.

In his letters, Proust expressed some ambivalence about the fate of his manuscripts and papers. In 1919, he asked of a friend: “What would you say if a man decided to keep to himself, as autographs, Voltaire’s correspondence, or Emerson’s? A private collection must be made into a museum, or else it deprives the community.” The following year, he decided to add plates from the Jeunes filles composite manuscript to all fifty copies of the luxury edition of that book. Yet, while entertaining an offer for the sale of his manuscripts in 1922, he admitted to his friend Sydney Schiff: “It is not very pleasant to think that anybody (if people still care about my books) will be allowed to consult my manuscripts, to compare them to the definitive text, to infer from them suppositions that will always be wrong about the way I work, the evolution of my thinking, etc.”

One hundred years later, the vast numbers of editions, translations and adaptations of Proust’s books, as well as the prodigious amounts of scholarship published on the subject, are evidence that people still care about his work. With this exhibition and continued work on our collection, we hope to have met Proust’s wish not to deprive the community of the opportunity to discover the work and life of one the major novelists of the 20th century. CS

******************************************************************

A basic bibliography of works by and about Marcel Proust