If you followed the news this past summer, you likely noticed that there was much talk of flags and their significance. This was especially the case for the State of South Carolina as legislation was passed to remove the Confederate battle flag from the grounds of the capitol in Columbia. This came after a horrific mass killing took place at the hands of a white supremacist who had previously been photographed brandishing not only the Confederate battle flag, but also those of apartheid-era Rhodesia and South Africa. Much has since been written about the implications of flags in this context.

The potent symbolism attached to a flag’s history may be manifested in various and complex ways – ways that may also change over time. The study of these issues is known as vexillology (from Latin vexillum; “flag, military ensign, banner”), a term coined by American flag historian and expert Whitney Smith in 1958.

Even before it is made official, considerations of a flag’s design are often highly politicized, as seen in the current case of New Zealand’s various proposals to change their national flag. In the case of the Republic of Cabo Verde, a Portuguese-speaking West African island nation also known in English as Cape Verde, the changes from one national flag to another have heralded the various changes to the nation’s administration and political configuration over the last fifty years.

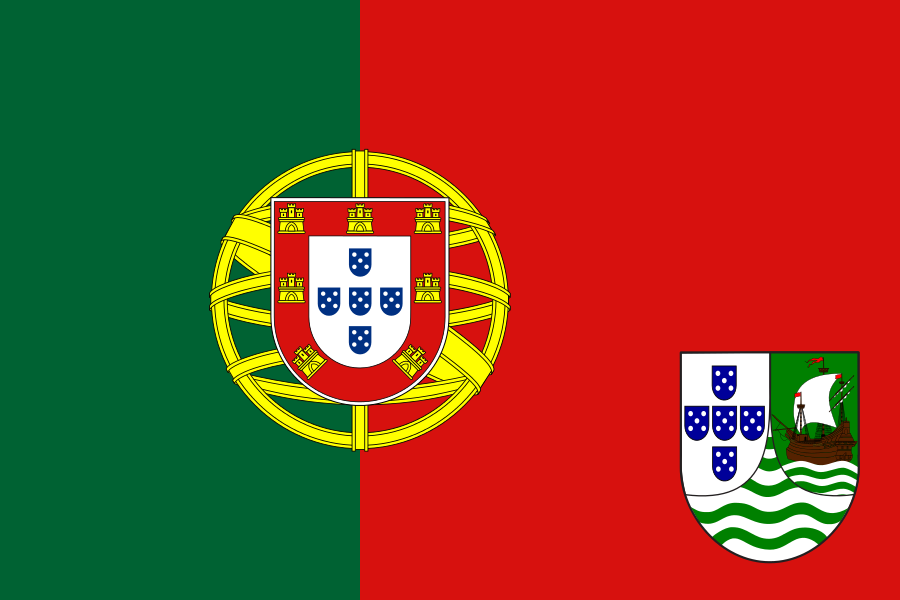

Here is the flag that was proposed for the territory during the 20th century while it was still under Portuguese rule (until 1975), but was never fully instituted due to various historical instabilities:

We can see the use of the ancient Portuguese flag – itself a conglomeration of various symbols dating back to both the Age of Discovery (c.1300-1600) and the Middle Ages (c.1100-1300), with a unique coat of arms for the colony of Cabo Verde in the bottom fly (“right corner” in vexillological terms). The ship symbolizes the Portuguese arrival at the previously uninhabited islands in the mid-to-late 15th century and the islands’ subsequent importance as a depot in triangular trade. The green sky and waves refer to not only the sea, of course, but also to the second word in Cabo Verde’s name, which means “green” in Portuguese.

Next we have Cabo Verde’s first national flag after it had declared independence from Portugal on July 5th, 1975 and was still united with Guinea-Bissau (formerly Portuguese Guinea) on the African mainland:

Clearly some major changes in policy had taken place. In fact, since those fighting for independence from Portugal – some since the 1960s – were socialists allied with the Soviet bloc under the aegis of PAIGC, the “African Party for the Independence of [Portuguese] Guinea and Cabo Verde,” which is today’s left-center PAICV party, it is not surprising that their eventual victory would be reflected in the fledgling nation’s new flag. The red, yellow, and green bars are traditional African colors symbolizing the struggle for freedom, mineral wealth, and the earth, respectively. But in this context, red can also denote socialism. The black star is a symbol of African/black solidarity that can also be found in the flags of Ghana and Guinea-Bissau as well as within the liberation symbolism of Jamaican Black Nationalist and Pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey (1887-1940). The ears of corn flanking the star stand for the importance of agriculture and traditional rural communities. The clam shell at the corn’s base hints at the great significance of the sea to the archipelagic nation.

When full democracy was obtained in Cabo Verde in 1990 with the admission of a second political party, the Movimento para a Democracia (MpD; “Movement for Democracy”), a new flag was called for. Thus, in 1992, the following was unfurled for the first time:

As we can see, almost all of the socialist-leaning, Afrocentric symbolism is gone. In its place is a scheme at least partially influenced by the red, white, and blue of the American flag, which hints at the fact that Cabo Verde and the USA maintain close and friendly relations to this day. The ten yellow stars arranged in a circle represent the ten islands of the Cape Verdean archipelago, though the islands’ actual relative position forms more of a flying-V shape. The blue represents the ever-present sea surrounding the islands. The red still stands for struggle/sacrifice as in the previous flag and the white bands stand for hope and/or peace, as in many other flags of the world. The intention with this particular change in design stems from Cabo Verde’s policies during the last 25 years of promoting homegrown unity and identity while simultaneously fostering links with a wide range of foreign partners such as Cuba, China, various member-states of the European Union, and the United States.

So what’s in a flag? A whole lot, once you stop to take a closer look.

Glossary of some vexillological terms:

- charge – any part of a flag that features a design in the foreground

- canton – a distinct rectangular area marked off in a flag’s corner

- hoist – the left side, where a flag would be attached to a pole

- fly – the right side, where a flag might flutter in the wind

- saltire – an X shape, as in the Union Jack of the United Kingdom

- coat of arms – a more complex design incorporating elements from heraldry, usually traceable back to a specific dynastic family

For more on this topic, check out these links as well as print titles from the University of Illinois Library and its affiliates:

Gideon, Richard, Ed. 2003-2015. American Vexillum Magazine. Self-published.

Shaw, Caroline, Compiler. World Bibliographical Series: Cape Verde. Oxford: Clio Press. (IAS Reference/Non-circulating).

Smith, Whitney. 1975. Flags Through the Ages and Across the World. New York: McGraw Hill.

Smith, Whitney. 2001. Flag Lore of All Nations. Brookfield, CT: Millbrook Press.

The Urbana Free Library. 2015. “Flag of Earth.” Blogs. 11 August 2015. Online: Accessed 16 September 2015.

Znamierowski, Alfred. 2010. The World Encyclopedia of Flags: The Definitive Guide to International Standards, Banners, and Ensigns. London: Southwater.