Vignette By: Donald Planey

Later in life, Dr. Baron would sometimes allude to his socialist roots, dating from his association with the Labor Youth League in the 1950s. But during his time as a PhD student at the University of Chicago, he wrote pieces published in the Chicago Maroon on socialist organizing, anti-imperialism, urban racial segregation, and the purges of left-wing intellectuals occurring across the U.S. While the University of Chicago had a history of censoring dissident academics, it also resisted the extremes of the red scare. The student newspaper, the Chicago Maroon, served as an avenue for Baron to express his convictions.

Dr. Baron did editing work for the Chicago Maroon while serving as a public voice for the Labor Youth League, a student-oriented spinoff of the American Communist Party. Eventually, Baron would leave the LYL, citing their unwillingness to focus on fighting racial segregation in Chicago’s education system as a major cause of his break. But while at the University of Chicago, he identified with the LYL enough to write for the Chicago Maroon on their behalf. In one instance, Baron wrote a letter to the paper that was meant to serve as a public response to a debate challenge from the Socialist Youth League, a Trotskyist counterpart to the LYL. The SYL had declared that with the failures of Stalin and the Soviet Union, as well as the challenge of the red scare, socialists needed to find a new direction. Speaking on behalf of the LYL, Baron agreed with the SYL’s criticisms of the Soviet Union, but insisted on public debate on crucial social issues of the day as the first step forwards for a possible reinvention of socialist politics.

In a letter dating from 1979, Baron described himself as a product of the Popular Front[1]: The Depression-era moment when the American Communist Party successfully opened up and initiated successful organizing projects, supporting the New Deal while advocating for peaceful engagement between the U.S. and the Soviet Union. But from an early date, Baron showed that he was no orthodox communist. One of his first major organizing projects was the push for student co-op housing in Hyde Park, marking the earliest evidence of his interest in promoting local self-governance in U.S. cities.

According to Dr. Lou Turner’s interviews with Dr. Baron, Paul Robeson was a crucial inspiration throughout his life, representing another aspects of his intellectual roots in postwar socialism. At multiple points throughout the 1950s, Dr. Baron emphasized the corrosive effects of McCarthyism on the U.S.’s ability to engage in public discussion of foreign policy and domestic social issues. In one shockingly prescient article in the Chicago Maroon in 1954, Baron warned of the U.S.’s growing involvement in “Indochina” (Vietnam) as proof that the U.S. was losing the ability to imagine foreign policy outside the framework of military intervention.

While studying at Amherst College, Dr. Baron made lifelong friends with Amon Nikoi. This friendship would open Baron to the subject of anti-colonial liberation and the relationship between autonomy and development. Dr. Baron continued to correspond with Amon Nikoi as late as 1995.

Baron also served as a delivery manager for the Chicago Maroon, perhaps providing him with early “entrepreneurial” experience, as he would later phrase his approach to organizing. In one of his first significant published writings, he reviewed an early collection of the Austrian School’s developing approach to economic history in the paper. He strongly objected to its cartoonish portrayal of the Marxian critique of capital, noticing from an early point many of the discursive techniques neoliberal academics used to promote their ideas, such as avoiding empirically-testable hypotheses in favor of litigating axiomatic principles.

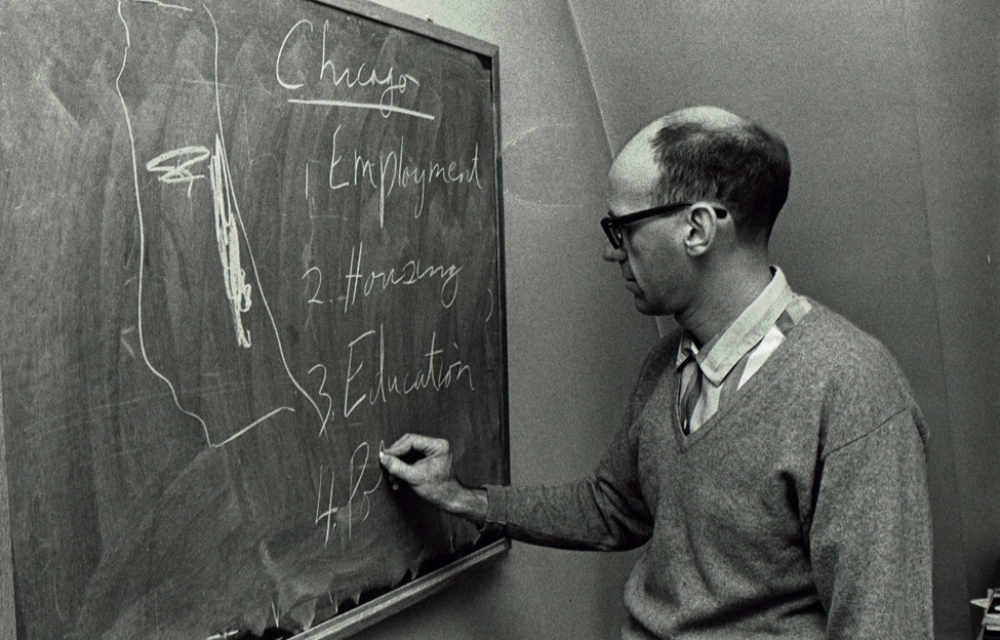

In his student co-op housing work, he helped to draft a proposal for co-op housing units for submission to the University of Chicago administration. Other details about this project are currently unavailable to the Hal Baron Project. Baron also gave speeches on the challenge of racial segregation that were advertised in the Chicago Maroon, but additional details on the kind of audience these talks drew in, or their impact, are unknown to us.

Baron’s appearances in the Chicago Maroon taper off after the 1950s, around the time he completed his dissertation. His final appearance in the Chicago Maroon came in 1968, in a promotion for an event meant to bring Chicago’s religious leaders into conversation with the emerging Black Power movement.

[1] Muhammad Ahmad-Correspondence, Hal Baron, 1980-1982. 1980-1982. The Papers of Muhammad Ahmad (Max Sanford). Personal Papers Collection of Muhammad Ahmad. Archives Unbound. Web. 16 Nov. Gale Document Number SC5003272048.