The earldom of Montemar had originally been given to Pedro Carrillo de Albornoz y Esquivel de Guzmán in 1694 for his commendable military service. Following his example, the third count of Montemar, José Carrillo de Albornoz y Montiel also became a war hero and was rewarded with the viceroyalty of Sicily among other appointments. For his services Phillip V conceded him the dukedom of Montemar and the title of Great of Spain in 1735. After his death, the greatness of Spain and the dukedom were transferred to his only daughter Maria Magdalena Carrillo de Albornoz y Antich but the earldom and its entailed estate were transferred to his first male cousin Diego Miguel Carrillo de Albornoz y la Presa (IV count of Montemar). Diego Miguel was born in Lima in 1695 to Diego Bernardo Carrillo de Albornoz y Esquivel de Guzmán, born in Seville and with a brilliant military career, and Rosa María de Santo Domingo de la Presa y Manrique de Lara, born in Lima and descendant of prominent crown officials. In 1723 Diego Miguel married Mariana Bravo de Lagunas y Villela, Lady of the Mirabel Castle, and they had 11 children: Rosa María, Diego José, Fernando, Juan Bautista, Clara María, Pedro José, Lucía, José, Juan Antonio, Manuel, and Isabel.

Diego José Carrillo de Albornoz y Bravo de Lagunas became the fifth count of Montemar when his father Diego Miguel passed away in 1750. As first son, Diego José had inherited the mayorazgo that included an appointment as councilor of Panamá and Lima and also the notary of Mar del Sur.[1] His brother Fernando, who would succeed him as VI count of Montemar, was mayor (alcalde) of the Santa Hermandad and councilor of Lima but more importantly judge auctioneer of the Ramo de Temporalidades, a very coveted position as it guaranteed first-hand access to the Jesuits properties that were confiscated by the crown in 1767.[2] His brother Pedro was colonel of the militias of Chancay while Juan enjoyed the repartimiento of Huanta and Manuel was corregidor in Conchucos.[3] Regarding property, the members of the Carrillo family were among the most important landowners in the viceroyalty. The haciendas Puente and Ñaña were among the most productive properties in Lima, and their owners were Juan Antonio and Manuel. Likewise, Fernando owned the haciendas San Regis, San José, Hoja Redonda, and La Playa most of them in Chincha. Additionally, with the properties owned by Fernando´s wife, Rosa de Salazar y Gabiño (countess of Monteblanco), they owned more than 1000 slaves. His brother Pedro owned the hacienda San Ildefonso de Guaito in Huaura with more than 600 slaves, the hacienda Vilcahuaura, the Quinta de la Presa, and a gunpowder mill. In these haciendas they produced sugarcane and wine, and they imported wheat from Chile. Fernando for example imported mules from Tucumán in Río de la Plata and he also owned a bakery and a big warehouse in Bellavista, in the outskirts of Lima.[4]

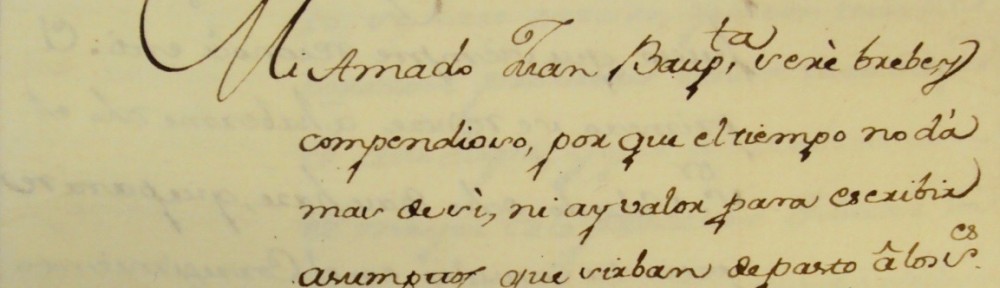

The letters from the collection were written by the V count of Montemar, Diego José, by his brother, Pedro José, and a few were written by his brother in law Don Francisco Manrique de Lara. In total, there are around 300 letters, exchanged between Lima, residence of most of the members of the family, and Madrid were Diego José lived. The content of the letters vary in theme and length. Topics range from greetings and family updates of marriage, to professional careers, army and security, vice-royal affairs and politics, trade and commerce, nobility, Indian affairs, legal affairs, etc. Several people are mentioned, since the Carrillos were related by blood or marriage with most of the Limeño elite in the viceroyalty, and Diego José was a regular in the court of Madrid and interacted with most of the main political figures of the era.

[1] A mayorazgo (primogeniture/entailed estate) was a legal mechanism –sanctioned by decree of the Crown- that prevented heirs from selling or distributing property so it could pass from generation to generation therefore remaining in a family. It was usually transferred to sons but in America daughters could inherit it too. Similarly, the mayorazgo could include public appointments like in this case. Chocano, Magdalena, “Linaje y mayorazgo en el Perú colonial” in Revista del Archivo General de la Nación, No 12, 1995, p. 130-131. In Diego José´s case, these appointments originally belonged to his grand parents Diego Bernardo and Rosa María. Diego Bernando had been corregidor of Cajamarca and mayor of Lima while Rosa María inherited the mayorazgo de la Presa that included a position as alderman (regidor) of Panamá and Lima as well as the benefits from the notary of Mar del Sur. Libro primero de Cabildos de Lima, segunda parte, Apéndices. París, Imprimerie Paul Dupont, 1900, p- 75-77.

[2] Ramo de Temporalidades was the branch of the royal treasury dealing with ecclesiastical properties confiscated to the Church. Rizo-Patrón Boylan, Paul, “Grandes propietarias del Perú virreinal: las Salazar y Gabiño” in Margarita Guerra et al., Historias paralelas: actas del primer encuentro de historia Perú-México, Lima, PUCP, 2005, p. 317.

[3] A repartimiento was a colonial forced-labor system imposed upon indigenous population who were forced to work low paid or non-paid labor for a number of weeks or months every year. It was abolished in 1780 due to the Tupac Amaru´s rebellion although it persisted after. See Fisher, John, El Perú borbónico (1750-1824), Lima, IEP, 2000, p.113-114. The Corregidor de indios was a chief magistrate that had responsibility over a province or district. Among their duties they had to deal out justice and collect taxes but they were also in charge of the repartimiento. Traditionally, this appointment was sold in Madrid and it was highly appreciated in some areas of the viceroyalty because of the revenue each corregidor could obtain from indian´s labor. See Moreno Cebrián, Alfredo, El Corregidor de indios y la economía peruana en el siglo XVIII, Madrid, Instituto Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo-CSIC, 1977, p. 14-15, 70-72.

[4] Rizo-Patrón Boylan, Paul, “La nobleza de Lima en tiempos de los borbones”, Bulletin Institut Français de Études Andines, 1990, 19, No 1, p.146.