For Colombia’s political history, the last couple of weeks were simultaneously the most promising, frustrating, intense, unpredictable, and confusing. Between September 26th and October 7th, 2016, a peace agreement was signed, voted and rejected; there was a risk of ending the ceasefire; the peace process was supported by massive rallies; there was no plan B ready, not even by leaders opposing the agreement; and, if all this does not sound confusing enough, the 2016 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to Colombia’s president, Juan Manuel Santos.

This is not the entire story, however. As with any other peace process, this is a matter of a long and complex political history.

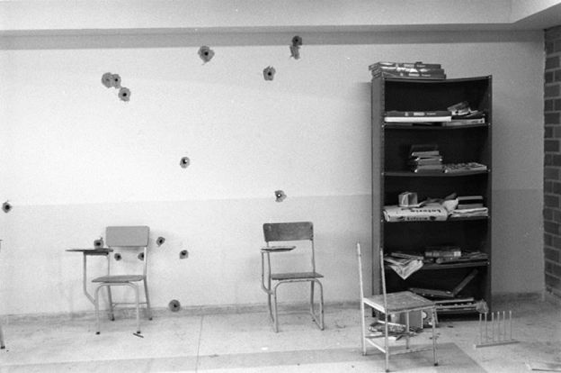

School affected by war in rural Colombia. Photo by Jesus Abad Colorado. Source: BBC Mundo

Unlike Colombia’s conflict being framed in terms of mere terrorism, which assumes there are “bad guys” who should be defeated by the “good guys”, the country’s political violence has developed between conservatives and liberal guerrillas since very early on in its republican history.

More recently, after the 1948 event known as El Bogotazo, confrontations between liberals and conservatives scaled in cruelty and intensity to the point that the 1950s are known, even today, as the time of La Violencia. As a result of the huge social inequities, marginalized territories, and the inherited issues of the 50s combining with the socialist revolutionary environment in Latin America, several political rebel groups emerged in the 1960s and 70s. From those came the three largest guerrilla groups: M-19, which disarmed in 1990 after a process that resulted in the 1991 constitutional reform; the ELN (Ejército de Liberación Nacional), which has approached peace negotiations still in progress; and FARC-EP (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia – Ejército del Pueblo), the largest rebel group in the country, and the protagonist of events these past two weeks. A fourth large paramilitary group, the AUC (Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia), emerged in the 1980s not as a political movement, but to defend private properties where the national army could not guarantee safety. The AUC went through a disarming process in 2006, which has been highly questioned due to both its lack of transparency and because of evidence of State’s support in some paramilitary attacks (more references about this topic here).

One more thing—drugs. Drug-dealing and other illegal economies permeated almost every one of these nonofficial armed groups, which added the “easy money” factor to an already complicated picture. Read more about Colombia’s political history in the work of David Bushnell, Jorge Orlando Melo, Marco Palacios, Alfredo Molando and Paul Oquist, among others. There are more than 400 entries at the library catalog about political violence in Colombia . Also, you can find additional resources about connections between drug-dealing and war in Colombia here.

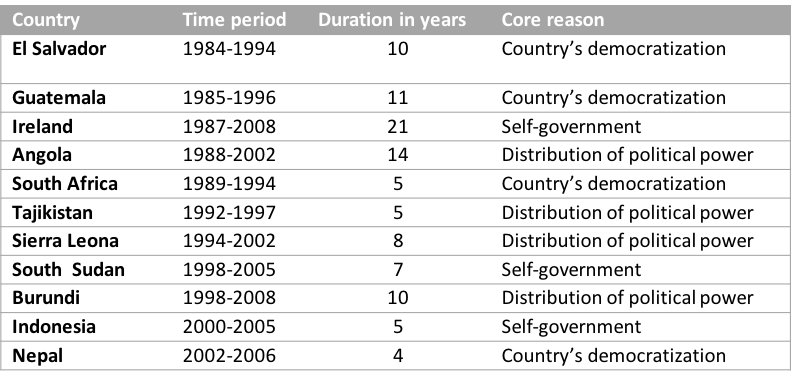

This most recent and internationally visible peace process with FARC was a 4-year negotiation of a 52-year long conflict, with previous attempts to reach a peace agreement occurring in 1982, 1991, 1992 and 1999-2002. Other conflicts in the last 32 years which were resolved through peace processes have lasted between 4 and 21 years long.

List of conflicts solved by peace process between 1984 and 2005. Source: School of Peace, Universidad Autonoma de Barcelona

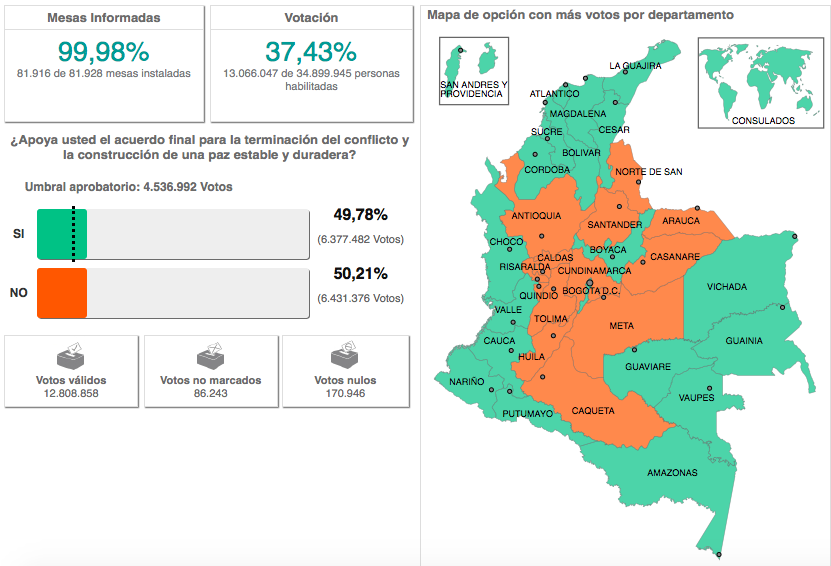

On August 24th the negotiation team from the Colombian government, rebel leaders and international observers announced in La Havana-Cuba that an agreement had been reached. The same day, the Colombian President announced a bilateral ceasefire. The agreement would be signed and brought to citizen vote, so an intense campaign period for and against the agreement began. With significant presence and support from international observers, the peace agreement was officially signed on September 26th by Colombia’s President, Juan Manuel Santos, and FARC leader Rodrigo Londoño –“Timochenko” after four years of negotiations. One week later, on October 2nd, the vote took place. In spite of all poll predictions and the overall national and international optimism, the “No” campaign at 50.21% won out over the “Yes” campaign by the very small margin of 0.43%. Such a close race combined with almost 60% of potential voters not voting revealed a deep polarization, not between people wanting peace and people wanting war, but over what is the best way to achieve a collectively desired peace.

Results from the vote on October 2 to support or reject the peace agreement. Source: Colombia’s National Registrar

Uncertainty and frustration came next. Leaders of the “No” campaign did not have a plan B for the process and showed to be a very heterogeneous group. The deadline was announced as October 31st. Faced with going back to open confrontation, citizens across the country brandishing mottos like “Don’t leave the table” and “Vigil for Peace” turned out for massive rallies to keep negotiations alive. These rallies included voters both for and against the agreement, as well as those who did not vote, and such strong public support pushed all parties to remain in dialogues. The Nobel Prize awarded (for some, too early) to President Juan Manuel Santos, adds an extra push to guarantee that a more robust and politically legitimate agreement is achieved.

Citizen support to the Peace Process, October 5th 2016, Bogota, Colombia.

Source: El Tiempo

Huge challenges remain ahead. The most urgent one is that all parties—the government, FARC leaders and the heterogeneous (somewhat erratic) opposition—manage to re-negotiate some points of the agreement, which are seen as “immovable” for both sides of the table. As observed in other international processes and complex political peace negotiations, the political will to compromise and commit to an agreement is critical. Compromise and agreement are required not only from combatants and politicians, but from every single citizen. Scholars point to such cases as South Africa and Rwanda as examples of compromise by parties through a special transitional justice system. Regarding this need for compromise, the School of Peace from Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona (AUB) show how in all of the 11 processes listed above, groups that fought during the armed conflict occupied influential political positions as a result of the peace process. In fact, one of the issues that generated fierce rejection from the opposition to the agreement is that it guaranteed political participation to FARC leaders.

Even if agreement is reached, an even larger challenge remains: Everyone—government, rebels, and civilians—fulfilling their promises. This, analysts say, is a key factor in preventing new armed confrontations from emerging, and scholars argue that in Sri Lanka, Liberia and Nepal the failure to fulfill agreements generated new waves of violence.

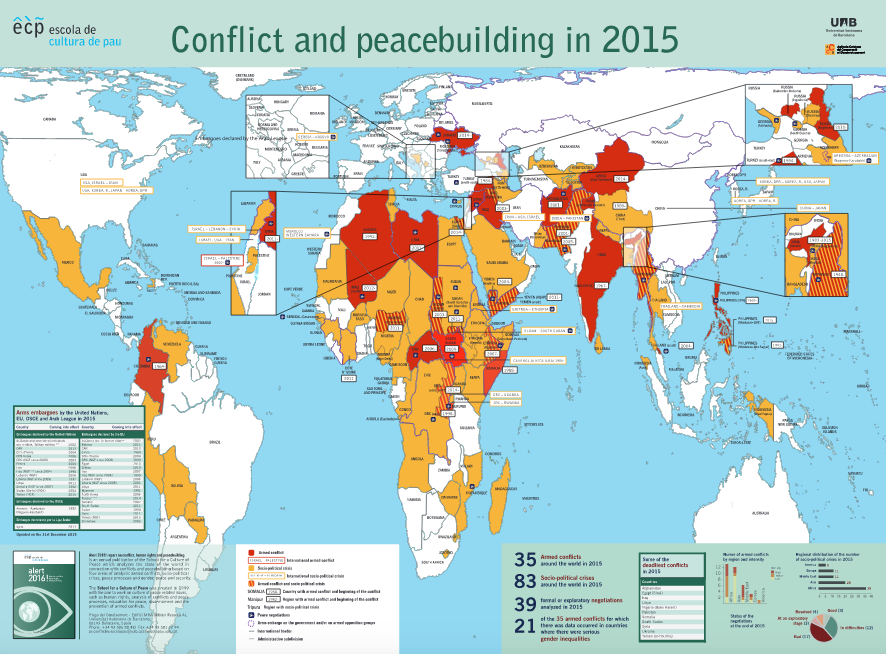

In any case, other international peace processes reveal that civil wars are rarely terminated by the victory of one of the parties. In the 2016 yearbook of peace processes developed by UAB’s School of Peace, of the 61 conflicts that ended over the last 35 years, 77% did so through a peace agreement, and 16.4% through military victory of one of the parties. However, there are still 56 active armed conflicts distributed across the world, which, in the 2016 yearbook, includes Colombia. Other countries with active wars are India, Senegal, Mozambique, Ukraine, Philippines, and Thailand (south).

Conflicts and Peace Building, 2015 map by School of Peace, UAB

Read more about armed conflicts and peace in Pakistan and African countries through the work of Adam Curle and Birgit Brock-Utne. Other important scholars on peace building and conflict resolution are Gene Sharp, Johan Galling, Betty Reardon, Roger Fisher and John Paul Lederach.

The yearbook asserts that “The culture of negotiation is now a reality”. As both a Colombian citizen and one of many people across the globe who wish to have a better world someday, I wholeheartedly hope that the culture of negotiation can be a reality in Colombia. Two Colombian films which offer a beautiful and intense experience of the complexity of the county’s political violence—and are available to the U of I community through Kanopy Streaming—are Los Colores de la Montaña by Carlos Cesar Arbelaez (2010) and La Sirga, by William Vega (2012).

Explore more about political violence and peace processes in other Latin American countries such as El Salvador and Guatemala. Also, explore the documentaries and films about Latin American history through Kanopy Streaming. This database includes films about political history, covering topics such as the Cuban Revolution and ‘El Che Guevara’, Nicaragua during the ‘Sandinista’ period, the consequences of violence in Guatemala, Peru in the aftermath of political violence, and the disappeared people during the Argentinian military regime, among many other documentaries and films.

If you want to delve more deeply into research about political history around the world, visit our International and Area Studies Library. Our subject specialists in Latin America, Africa, Middle East and North Africa, South Asia, Central Europe, Central Asia, and Global Studies/Political Science can always guide you with more specific research advice. See you there!