One student asked recently in studio class for suggestions/advice about hearing chords, in particular specific harmonies once the root is identified. At the time, I talked about the importance of hearing/singing the melody first, then the fundamental bass line, and being able to sing one of those while playing the other, which I think is certainly right.

Beyond that, I think there are several kinds of things we can do to improve our perception of chords. There is the idea of inner voices, and it is good to think of these, in the typical mainstream jazz context, as somewhat hierarchical, so we might practice first hearing thirds and sevenths, either isolated (hearing/singing the 3rd, for example on each chord) or in context (voice leading 3rd to 7th and vice versa). After that, we could possibly also look briefly at 5th to root and root to 5th, but the next big step is adding the 9th, resulting in 9th to 5th voice leading and the inverse, and then the 13th, with 9th to 13th, though that is limited in many cases because we don’t really hear 13th on subdominant minor 7th chords (like A on a C min7 in a ii V I in Bb). So, in sum, working on the ability to hear a given chord tone in a given harmony will really help open up the ear.

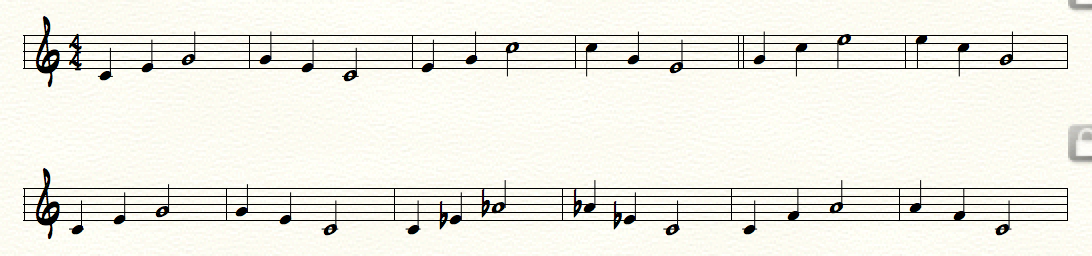

The other approach, very important, is developing the ability to sing chords well from any note. This is what I like to call the fundamental exercise, by which I just mean working anything, scale, chord, etc., from every part of it. So, the fundament exercise on a C Major triad would look like this:

The first line is singing the C Major triad up through each note from each note. The second line is the same idea, but singing the three major triads which contain C. You should work this on minor, diminished and augmented triad. With augmented, of course, the last line is basically moot, due to the symmetry of the augmented triad. Later, you can add the sus triad, CFG for example, and the major diminished triad, CEGb, or CEF#. These are very important when we add sevenths.

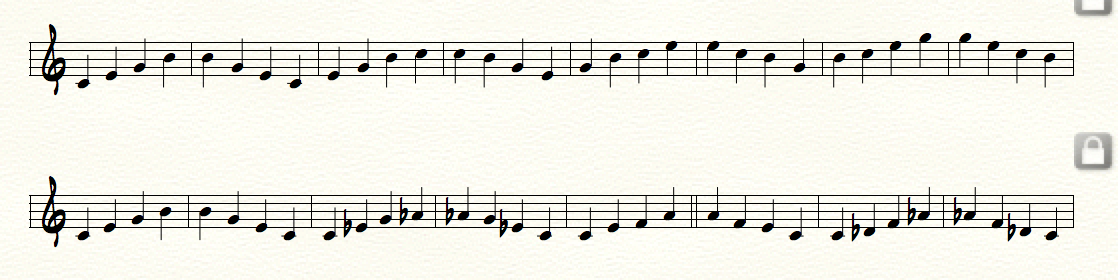

The same idea applied to 7th chords, here the Maj.7, would look like this:

Line one is C∆7 in all inversions, line 2 is all four ∆7 chords containing C.

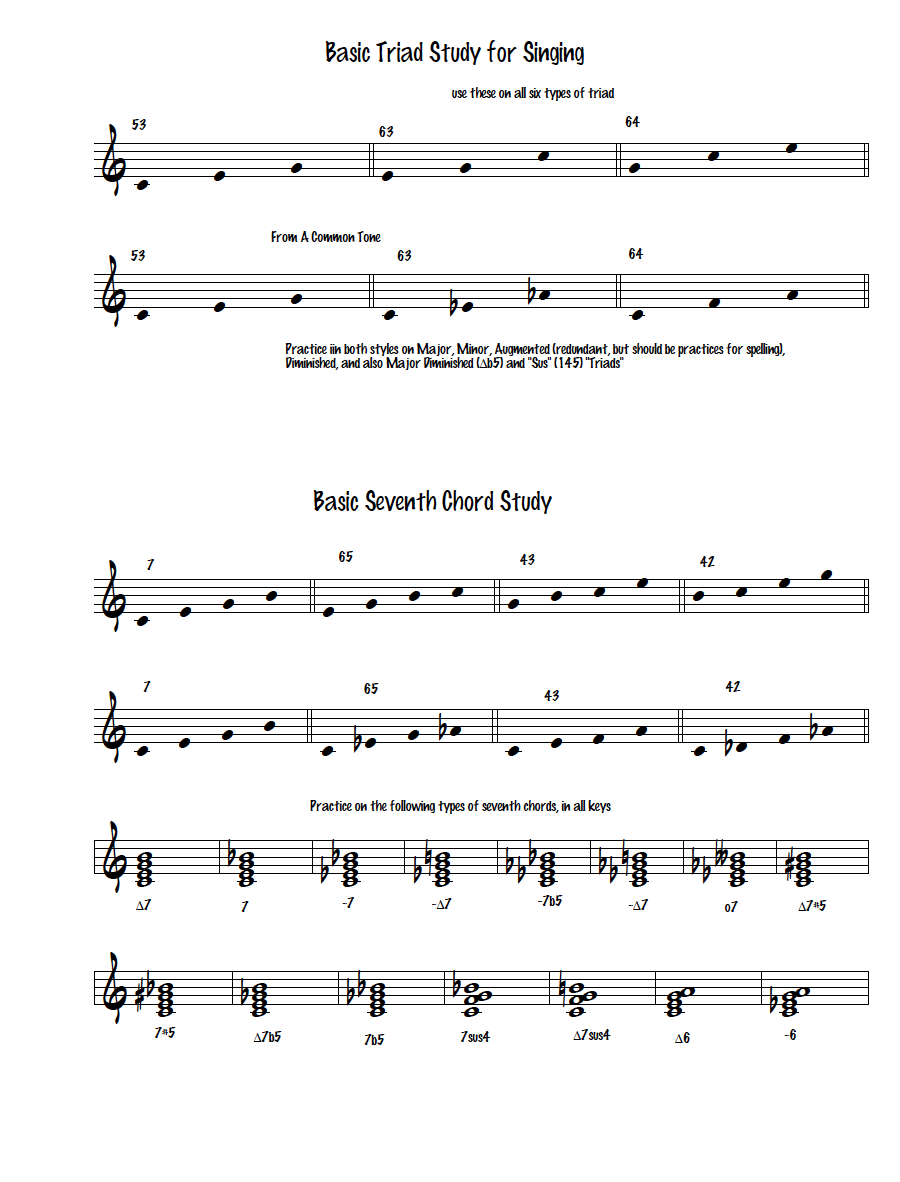

Here’s a summary, road map of the whole concept. It’s a lot of work, so just do a little bit, and keep doing it, and your ear will improve.

Be sure to also think about how this would be done with scales. Tip: We really only need to know 4 scales to play most of jazz- the major scale, the melodic minor (so-called ascending form), the whole tone scale and the octatonic scale. Most of what we find are permutations or subsets of those four. So, if you learn the major scale in this way, you also have learned aurally the structure of all the modes, for example, and you’ve learned it well.