Please help us feed hungry people by improving dairy cattle in developing countries.

Author Archives: mbwheele@illinois.edu

Beth Bangert wins IETS CANDES Committee Travel Award.

Beth Bangert (left), M.S. student in Dr. Wheeler’s Group won an IETS CANDES Committee Travel Award to present her research entitled, “The efficiency of an adapted beef cattle protocol to produce in vitro-derived embryos from oocytes collected via surgical ovum pick-up from live white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) donors under captivity in central Illinois”, at the International Embryo Technology Society’s 50th Anniversary Annual Conference in Denver, Colorado on January 9, 2024.

Dr. Wheeler’s Group Presents Six Abstracts and Posters at the IETS’ 50th Anniversary Annual Conference in Denver, Colorado.

Dr. Wheeler’s Group Presents Six Abstracts and Posters at the IETS’ 50th Anniversary Annual Conference in Denver, Colorado. The abstracts were entitled:

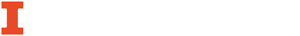

Dr. Chanaka and Graduate Student Ken Wilson discuss a poster at the IETS Conference.

Bangert, E., Shipley, C., Rabel, R.A.C., Garrett, E., Milner, D. J., Marchioretto, P.V., Spencer, K., Allen, C., and Wheeler, M.B. (2023). The efficiency of an adapted bovine IVF protocol to produce in vitro-derived embryos from oocytes collected via surgical ovum pickup from live white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) donors under captivity in central Illinois. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 36, (2) 165-166 https://doi.org/10.1071/RDv36n2Ab32

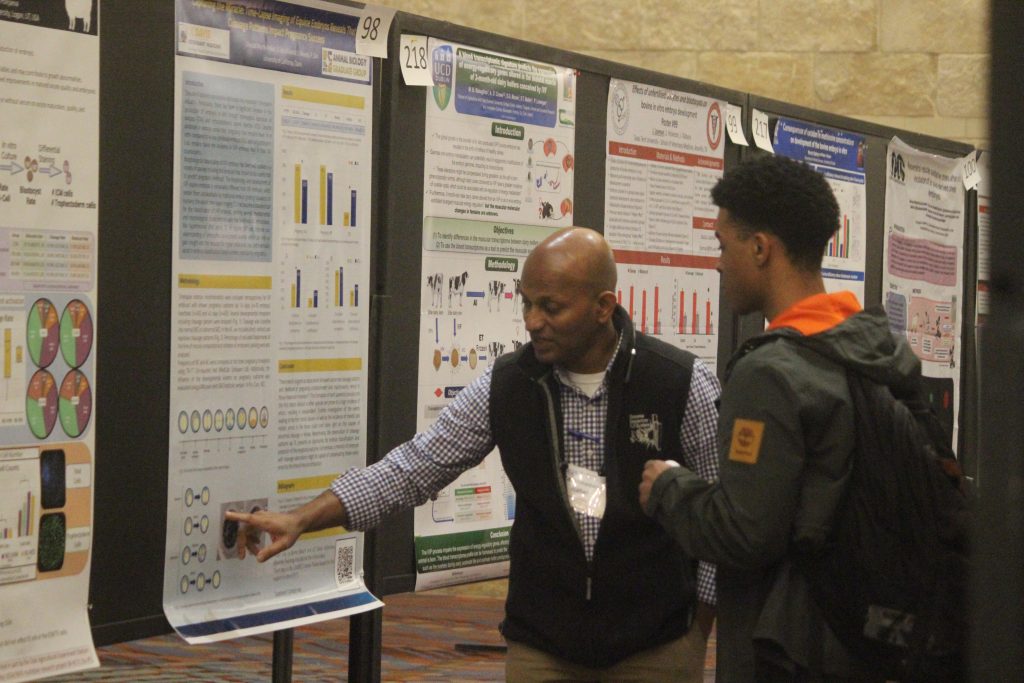

Beth Bangert at her poster.

Glassey, J.R., Rabel, R.A.C., Milner, D.J. and Wheeler, M.B. (2023) Strontium enhances in vitro osteogenic differentiation of porcine adipocyte–derived stem cells. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 36, (2) 265-266 https://doi.org/10.1071/RDv36n2Ab220

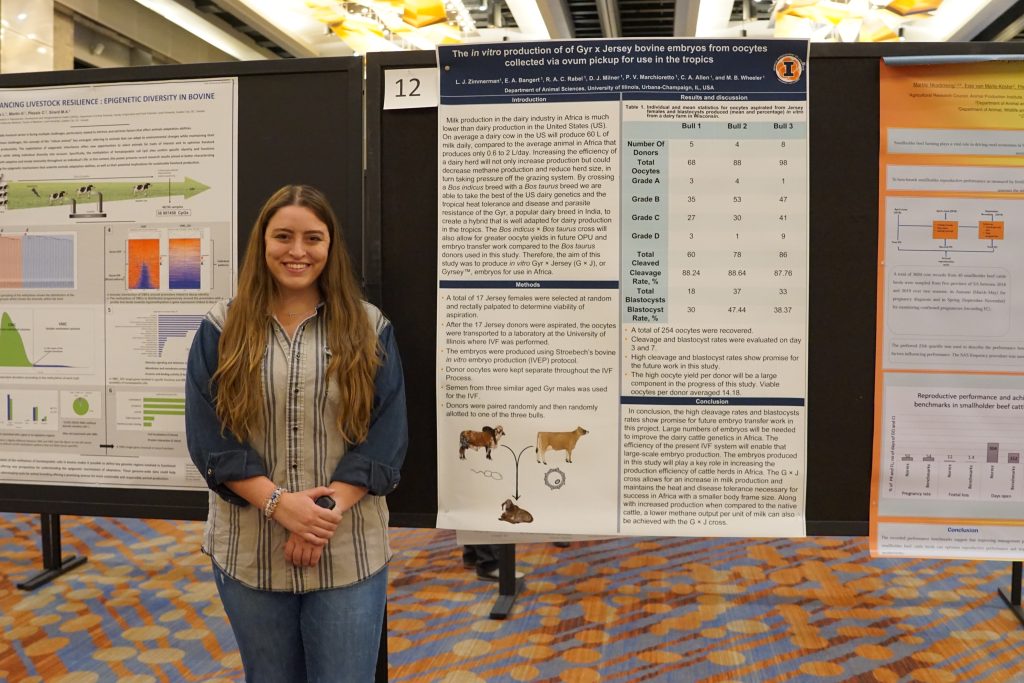

Dr. Chanaka Rabel discussing his and Joe Glassey’s poster with one of the IETS conference delegates.

Marchioretto, P.V., Rodriguez-Zas, S L., Womack, S.A., Lindsey, B.R., Milner, D.J., Rubessa, M., Wilson, K.C. and Wheeler, M.B. (2023). Effect of dominant follicle removal before ovum pickup in Girolando cattle. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 36, (2) 251-252 https://doi.org/10.1071/RDv36n2Ab193

Monzani, P.S., Sangalli, J.R., Sampaio, R.V., Guemra, S., Zanin, R., Adona, P.R., Berlingieri, M.A., Cunha Filho, L F.C., Mora-Ocampo, I.Y., Pirovani, C P., Meirelles, F.V., Ohashi, O. and Wheeler M.B. (2023). Human proinsulin and insulin production in the milk of transgenic cattle. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 36, (2) 231 https://doi.org/10.1071/RDv36n2Ab155

Womack, S.A., Bethke, E.B., King, W P., Milner, D.J., Rubessa, M., Marchioretto, P.V., and Wheeler, M.B. (2023). Development of a porcine model for the testing of the RapidVent emergency ventilator for the treatment of COVID-19 infection. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 36, (2) 219 https://doi.org/10.1071/RDv36n2Ab132

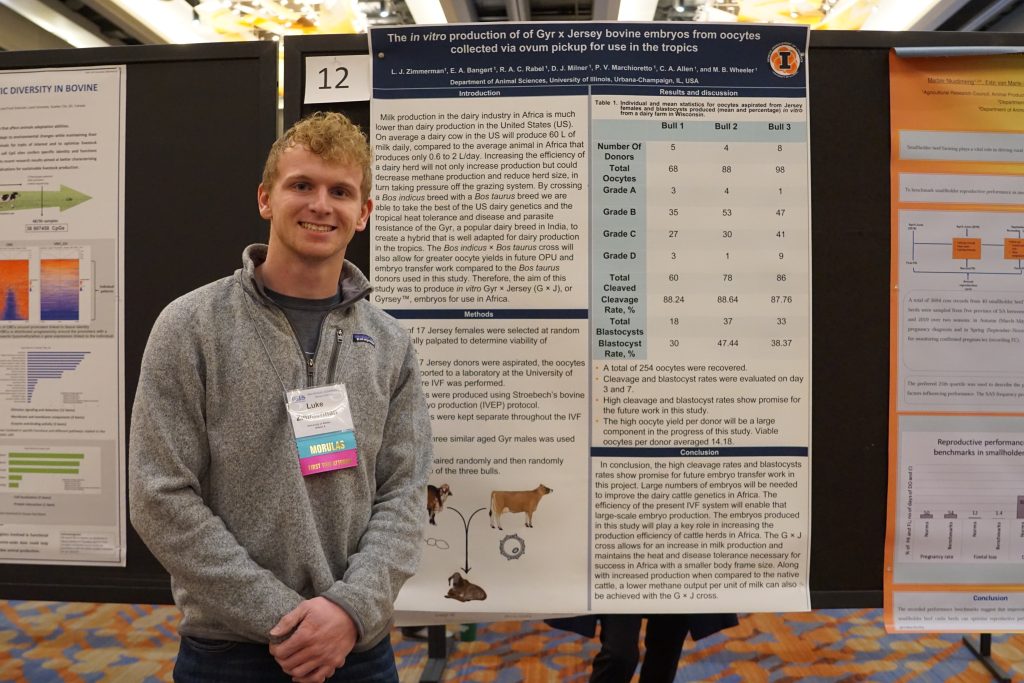

Zimmerman, L.A., Bangert, E. A., Rabel, R. A C., Milner, D. J., Marchioretto, P.V., Allen, C.A. and Wheeler, M.B. (2023). The in vitroproduction of Gyr X Jersey bovine embryos from oocytes collected via ovum pickup for use in the tropics. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 36, (2) 155 https://doi.org/10.1071/RDv36n2Ab12

Luke Zimmerman standing by his poster at IETS

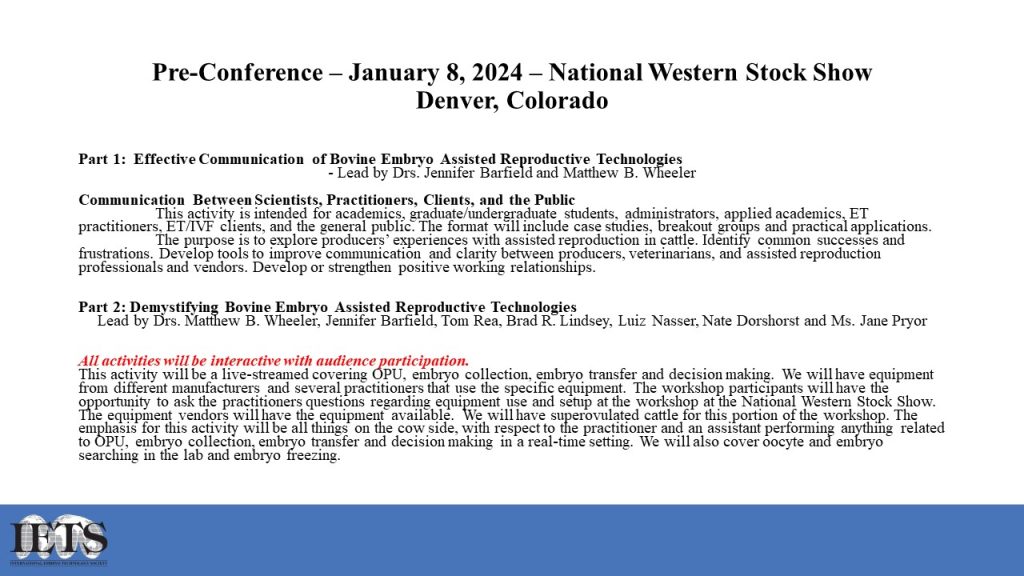

Dr. Wheeler leads Pre-Conference Symposium at the International Embryo Technology Society’s 50th Anniversary Annual Conference in Denver, Colorado.

Dr. Wheeler leads Pre-Conference Symposium at the International Embryo Technology Society’s 50th Anniversary Annual Conference in Denver, Colorado.

The IETS Pre-Conference Symposium 2024

Communicating and Demystifying Bovine Embryo Assisted Reproductive Technologies

Sponsored by WTA Technologies LLC, University of Illinois, Colorado State University, AETA, and

Ovitra Biotechnologies.

Climate-smart cows could deliver 10-20x more milk in Global South

ACES NEWS

Explore News by:

October 31, 2023

Lauren Quinn

ANSC Livestock Breeding International

Herd of quarter-Holstein, three-quarter-Gyr cattle

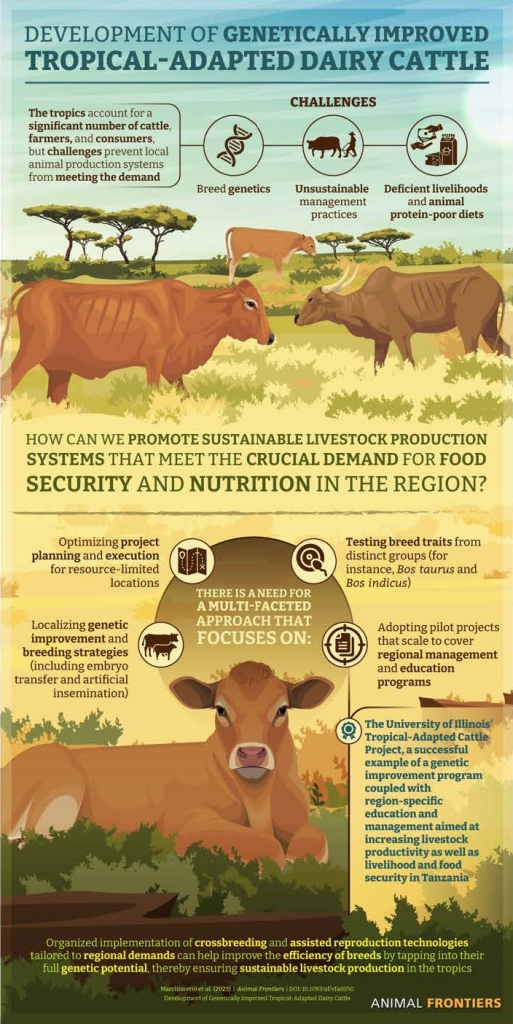

URBANA, Ill. — A team of animal scientists from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign is set to deliver a potential game changer for subsistence farmers in Tanzania: cows that produce up to 20 times the milk of indigenous breeds.

The effort, published in Animal Frontiers, marries the milk-producing prowess of Holsteins and Jerseys with the heat, drought, and disease-resistance of Gyrs, an indigenous cattle breed common in tropical countries. Five generations of crosses result in cattle capable of producing 10 liters of milk per day under typical Tanzanian management, blasting past the half-liter average yield of indigenous cattle.

After breeding the first of these calves in the U.S., project leader Matt Wheeler, professor in the Department of Animal Sciences in the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences (ACES) at Illinois, is ready to bring embryos to Tanzania.

“High-yielding Girolandos — Holstein-Gyr crosses — are common in Brazil, but because of endemic diseases there, those cattle can’t be exported to most other countries,” Wheeler said. “We wanted to develop a high health-status herd in the U.S. so we could export their genetics anywhere in the world.”

Wheeler’s team plans to implant 100 half-blood Holstein-Gyr or Jersey-Gyr embryos into indigenous cattle in two Tanzanian locations this March. The resulting calves will be inseminated through successive generations to create “pure synthetic” cattle with five-eighths Holstein or Jersey and three-eighths Gyr genetics. Unlike Girolandos, Jersey-Gyr pure synthetics do not yet have an official name.

Half-blood Holstein x Gyr calf

Pure synthetics are worth the time and effort; once the five-eighths/three-eighths genetics are established, they’re locked in. In other words, calves from successive matings will maintain the same genetic ratio.

“The whole idea is to keep the disease and pest resistance linked together with the milk production so that as you breed, those traits don’t separate,” Wheeler said. “That’s going to be the challenge in developing countries; until you get to the pure synthetic generation, there will always be the temptation to breed to the bull down the road, losing the effect.”

Wheeler’s team, including coauthor Moses Ole-Neselle of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), cares about getting this effort right. Although developing the embryos took years of meticulous work, they’re not stopping there. The team hosted its first online course on bovine assisted reproduction technology last summer, including 12 participants from Tanzania. And there’s more to come.

“It was important to start training the first group of veterinarians and graduate students to adopt the technology, so when we get there, it’s not a foreign thing,” Wheeler said. “The Tanzanian government wants this training and student exchanges. We’re going to continue investing in this program for as long as it takes.”

Wheeler recognizes the best genetics and most comprehensive training won’t amount to much if the plan doesn’t account for the local culture. With advice from collaborators like the Tanzania Livestock Research Institute and Teresa Barnes, director of the Center for African Studies at Illinois, Wheeler has already adjusted his strategy to accommodate the preferences of local Maasai herdsmen.

“We’ve learned some Maasai clans strongly prefer smaller, red cattle, so the Holstein crosses we made initially, which were large and black, weren’t going to work,” he said. “I had to start over with Jerseys, which set us back a bit. It will be worth it if they’re better accepted.”

But some aspects of Tanzanian cattle management will have to change to realize the full potential of the improved genetics. For example, Wheeler said nomadic Maasai herders often graze cattle 25 miles from their enclosures each day, limiting the energy available for milk production.

While the project is still in its early stages, it represents a step toward more climate-resilient animal agriculture, the topic of the special issue of Animal Frontiers in which Wheeler’s article is published. While Wheeler’s current priority is to bolster food security in the Global South where climate change is hitting hardest, he said the same technology could be used to protect cattle from changing climates here in the U.S. and around the world. In other words, tropical genetics could be inserted into our already high-yielding cattle to better withstand heat, drought, and disease.

“These cattle would work very well in Mexico, Texas, New Mexico, and California. Maybe it’s time to start thinking about that now,” Wheeler said. “People don’t usually think that far ahead, but my prediction is that people are going to look back and realize having tropical genetics earlier would have been a good thing.”

The study, “Development of genetically improved tropical-adapted dairy cattle,” is published in Animal Frontiers [DOI:10.1093/af/vfad050]. Authors include Paula Marchioretto, Chanaka Rabel, Crystal Allen, Moses Ole-Neselle, and Matthew B. Wheeler. This work was partially supported by the USDA Multistate Project W-4171, the ACES Office of International Programs, the University of Illinois National Resource Center in African Studies via funding through the Department of Education’s Title VI grant program for 2022-26 and the Ross Foundation (Agreement #635148).

Story Source(s)

Dr. Wheeler presented with the 2023 Spitze Land-Grant Professorial Career Excellence Award sponsored by the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences.

Image

This award is presented to recognize the professorial career of tenured faculty in their performance and commitment to teaching and advising; research and publications; extension and public service; faculty governance; and participation in professional associations. The award, which was first presented in 2003, also memorializes the unique mission and rich history of the public land-grant university and exemplifies the continued opportunities it offers for worldwide contribution to the betterment of humankind and to democratic institutions in an ever-changing environment.

Tropical-Adapted Dairy Cattle Project Published in Animal Frontiers

Development of Genetically Improved Tropical-Adapted Dairy Cattle” Animal Frontiers, Volume 13, Issue 5, October 2023, Pages 7–15, https://doi.org/10.1093/af/vfad050

Ensuring food security in the tropics through livestock genetic improvement is goal of symposium

May 2, 2023

by Leslie Myrick

Animal scientists, economists, and colleagues from the humanities and other fields met on the University of Illinois campus in April to focus on livestock in the tropics and its role in food security.

The event marked the Seventh Annual International Food Security Symposium at Illinois facilitated by the Office of International Programs (OIP) in the College of Agricultural, Consumer and Environmental Sciences (ACES).

Each year the OIP selects a partner to work with to explore in depth a specific aspect of international food security. This year’s symposium was co-hosted by the Department of Animal Sciences and the Center for African Studies. Ten presentations spanned a wide range of topics built around the theme of “Ensuring Food Security in the Tropics Through Livestock Genetic Improvement.”

View the recorded presentations here.

View the symposium program and speaker bios here.

Students, faculty, and staff as well as visitors from other universities and around the world presented and listened, asked questions, learned from each other, and made plans to work together moving forward.

Additionally, a poster presentation showcased ongoing research work led by students in the College of ACES.

The true value of the symposium will be ongoing as the connections made will foster future work to meet the challenges presented.

“We’ve already started talking about future collaborations with the speakers and others,” noted Crystal Allen, who along with Matt Wheeler led the symposium team from the Department of Animal Sciences.

Wheeler closed the symposium by telling a story of being in on a farm in Northeastern Brazil where the 16,000 cattle ate only cactus (cut into small pieces) and were milked by hand every day. Using this story as just one example, Wheeler said, “Dairy farmers will find a way. And we can all be involved in dairy finding a way. It’s not going to be easy. It’s not going to be tomorrow. But we can do it if we want to and can work together.”

Wheeler Lab Partners with Statz Bros. Dairy to Produce Jersey X Gyr Embryos for Tropical-Adapted Dairy Pilot Project in Tanzania

In late-December 2022, the Wheeler Lab went to Statz Bros. Dairy to aspirate 24 Jersey donors to collect oocytes. The oocytes were inseminated with Gyr semen to produce the embryos for the Tanzania Pilot Project. The oocyte collection was coordinated by Helix AgriSystems and Paramount Calves. The aspirations were performed by Dr. Andre Dayan of Dayan, LLC and the embryo production was overseen by Dr. Nate Dorshorst of GenOvations.

In early 2023, approximately 80 embryos will be transported and transferred to indigenous recipient cattle. The Tanzanian research partners include the National Ranching Company and the Tanzanian Livestock Research Institute. The Tanzanian collaboration is coordinated by Dr. Moses Neselle of FAO. Prior to and during the pilot project Tanzanian scientists, students and farm managers will be educated and trained in the basics of assisted reproduction, nutritional management and husbandry of embryo transfer calves. This knowledge transfer is an integral part of the pilot project and for future sustainability of the technology and the improved dairy genetics.

Department of Animal Sciences faculty/staff involved in this pilot project and education/training include Dr. Crystal Allen, Dr. Phil Cardoso, Dr. Paula Marchioretto, Dr. Derek Milner, Dr. Chanaka Rabel, Ms. Beth Bangert, Mr. Kenneth Wilson and Dr. Wheeler. Collaborators include Dr. Luiz Nasser of BORN Biotechnologies, Panama City Panama; Dr. Brad Lindsey of Ovitra Biotechnologies, Midway, TX; Mr. John Hull of JHGenetics, Alajuela, Costa Rica; Mr. Cavan Sullivan of Helix AgriSystems, Darlington, WI; Mr. Ken Norgard of Paramount Calves, Darlington, WI; Dr. Andre Dayan of Dayan, LLC, College Station, TX; and Dr. Nate Dorshorst of GenOvations, Lodi, WI.

See the video of the oocyte collection at Statz Bros. Dairy:

Dr. Wheeler Recognized by Carle-Illinois College of Medicine

Dr. Wheeler was recognized on September 29, 2022 for Excellence in Service and Commitment to the Carle-Illinois College of Medicine since its Inception by Dean Mark S. Cohen. Dr. Wheeler took part in the inaugural faculty and staff awards and recognition event at the Medical Sciences Building in Urbana.