“Wouldn’t it be strange? If when you made love to me, it somehow risked my life?”

Beth, Redline Collection

HIV/AIDS Epidemic

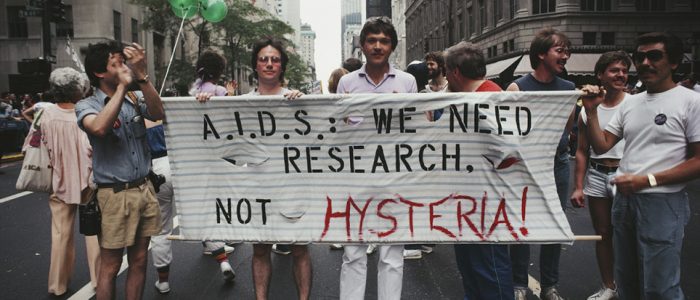

For many, the health crisis came into view with a headline in the July 3, 1981 edition of The New York Times: “Rare Cancer Seen in 41 Homosexuals.” But HIV/AIDS had likely already been in the U.S since the 1970s. Names like “gay cancer,” and “gay-related immunodeficiency” (GRID) circulated before the medical community settled on Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome, or AIDS. It would be a few more years before the virus that causes AIDS was identified as HIV-1, and many more before the first effective treatments were discovered. By 1986, the life expectancy of someone diagnosed with AIDS was fifteen months.

We know a lot more now than we did back in 1982 about where HIV originated and how it spread. But initially, people had no idea what was happening to their loved ones and very little research and medical treatment were available.

Women & Lesbians at the Frontlines

Women and lesbians, in particular, played a key role in the early fight against HIV/AIDS. They banded together to provide meals, medical care, organize protests and blood drives, and offer a hand to hold in the hospital when no one else would come. Those who served as nurses and chose to care for AIDS patients when many in the field refused, went on to establish and run the first AIDS-dedicated hospital wards.

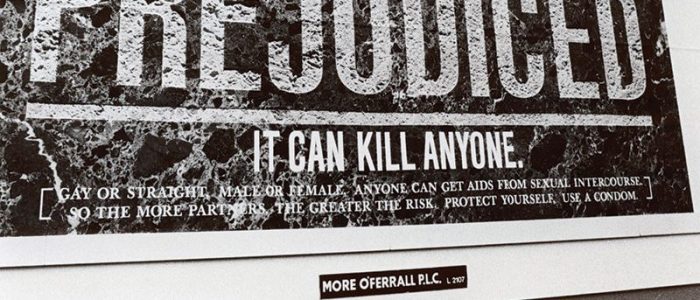

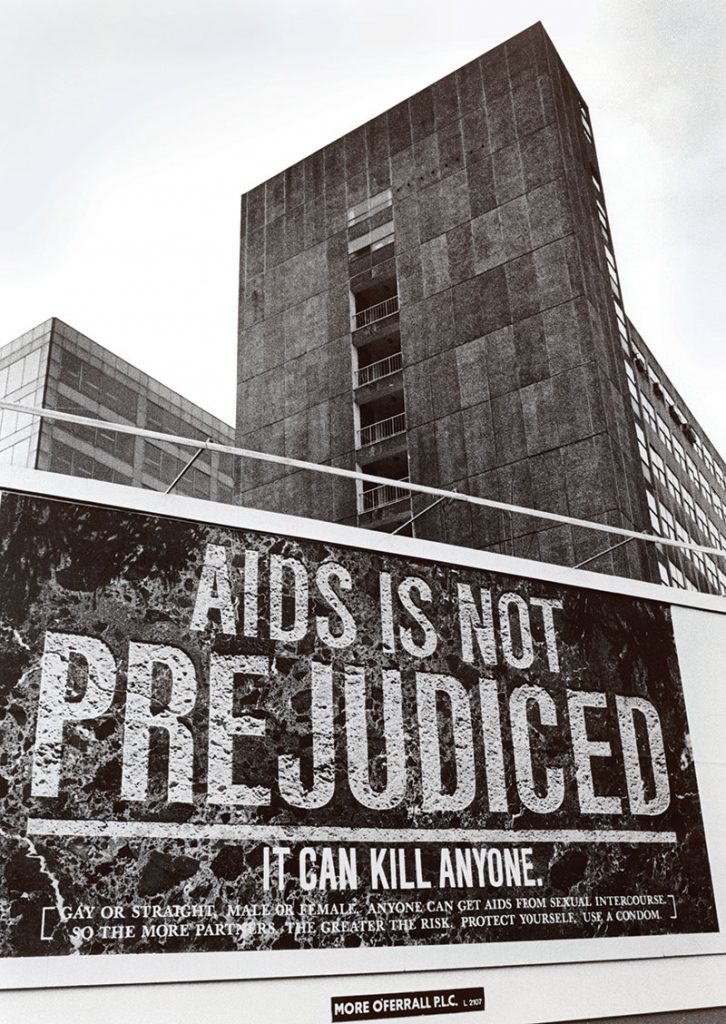

HIV/AIDS + Sex & Race

It is important to note that while men who have sex with men (MSM) were the first group of AIDS patients identified, HIV/AIDS severely affected women as well, particularly marginalized groups like sex workers, injection drug-users, and those with male sexual partners who fell into these risk factors. Many were also women of color. In fact, by 1986, 51% of women with AIDS in the U.S. were Black. Because they were not the initial focus of the epidemic, women with HIV/AIDS had a difficult time finding resources and information, accessing medical care, and being taken seriously. The first reports of women contracting the disease from sexual relations with HIV-positive men were as early as 1983, but the CDC did not change it’s definition to include the types of AIDS-related risks and illnesses associated specifically with women until 1993. Initially, women with HIV/AIDS were excluded from AIDS wards, research, funding, and even treatment trials.

The HIV / AIDS Timeline:

For a historical overview of the HIV/AIDS crisis starting from 1981, visit the Timeline at HIV.gov.

To view a comprehensive, interactive timeline with photos, video, and audio going back as far as 1959, visit the Avert HIV Timeline.

Early Milestones: (Source: HIV.gov)

- 1981 – First CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) mentions AIDS (before it was known by that name) specifying several cases of Kaposi’s Sarcoma and Pneumocystic Pneumonia in young, and previously healthy gay men.

- 1982 – Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), the first community-based AIDS service provider in the United States, is founded in New York City.

- 1982 – CDC uses the term “AIDS” (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome) for the first time in a new MMWR, and releases the first case definition for AIDS.

- 1983 – After a petition by psychiatric nurse Cliff Morrison, San Francisco General Hospital opens Ward 5B, the first dedicated in-patient AIDS ward in the U.S. The ward is run by Morrison and an all-volunteer staff—from nurses to janitors—who offer compassionate, holistic care for AIDS patients.

- 1983 – The World Health Organization holds its first meeting to assess the global AIDS situation and begins international surveillance.

- 1984 – Scientists conclude that AIDS is caused by a new retrovirus, which they later name human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- 1985 – The U.S Food and Drug Administration licenses the first commercial blood test to detect HIV. Blood banks begin screening the U.S. blood supply.

- 1985 – President Ronald Reagan mentions AIDS publicly for the first time, calling it “a top priority” and defending his administration against criticisms that funding for AIDS research is inadequate.

- 1986 – The U.S. Center for Disease Control (CDC) reports that more people were diagnosed with AIDS in 1985 than in all earlier years combined. The 1985 figures show an 89% increase in new AIDS cases compared with 1984. Of all AIDS cases to date, 51% of adults and 59% of children have died. The new report shows that, on average, AIDS patients die about 15 months after the disease is diagnosed. Public health experts predict twice as many new AIDS cases in 1986.

- 1987 – Approved in record time, zidovudine (AZT) becomes the first anti-HIV drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). (At $10,000 for a one-year supply, AZT is the most expensive drug in history.)

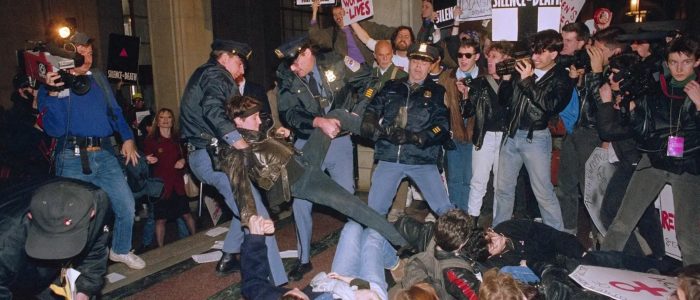

- 1987 – AIDS activist Larry Kramer founds the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) in New York City.

- 1987 – By the end of the year, 50,278 cases of AIDS have been reported to date, and 40,849 deaths.

- 2021 – Today, over 36 million people worldwide have died of HIV-related illness (WHO Statistics). While there is still no effective cure or vaccine, people with HIV can live long, healthy, AIDS-free lives, with low risk of transmission to sexual partners, by taking HIV medication known as antiretrovirual therapy (ART).

Chicago-specific:

- Illinois Masonic Hospital Unit 371, the first unit in the Midwest dedicated to AIDS patients, was established in 1984 by Dr. David Moore and Dr. David Blatt.

- ACT UP Chicago (Aids Coalition to Unleash Power) “formed in the late 1980s as a grassroots activist group committed to direct action protest for people with AIDS (PWAs) and AIDS/HIV awareness. Angry at government inaction and indifference at the rapidly increasing number of AIDS deaths in the 1980s, ACT UP sought to turn fear and sorrow into anger expressed through political action. The slogan, “ACT UP, fight back, fight AIDS,” is emblematic of the ACT UP ethos.” Danny Sotomayor was the founder of the Chicago chapter of ACT UP. ACT UP Chicago activists remember the 1980s.

Explore More about Lesbians & Women at the Frontlines

Explore More Race & Sex

- Timeline: 30 Years of AIDS in Black America (Frontline article)

- CDC Report: 30 Years of AIDS in Black America: An Overview

- A Timeline of Women Living with HIV: Past, Present, and Future

- Women and AIDS Brochure – 1984

- “Putting on a condom is just as easy” – safe sex campaign geared at women (and their partners)