Among other experiences this year, I’ve been fortunate to spend some extended time in Boise, Idaho, and Kearney, Nebraska. In both places, I talked with people about eco-tourism, environmental issues, protected areas, and sustainability, in various mixes. Both are very red states, and both economies have strong primary sectors. People talk about agriculture and livestock in both states, as well as forestry and mining in Idaho. Even so, they see the relationship between humans and nature in very different ways. Context matters.

In Idaho, I participated in the Idaho Environmental Forum. After that, I gave a talk on national parks at Boise State University. I also wrote a piece on the national parks for the Blue Review, an online magazine of the Idaho Center for History and Politics. In Nebraska, I participated in “Plains Safaris,” a conference on tourism and conservation in the Great Plains, sponsored by the Center for Great Plains Studies and Visit Nebraska. Idaho connected best to my teaching and research on Environmental Politics, while Nebraska connected to my teaching and research on Recreation and Tourism.

The occasions were very different, but it was striking that people in Idaho tended to talk about “environmental” issues while those in Nebraska tended to talk only about “conservation.” Not surprisingly, people in both places talked in terms of conservation when talking about hunting and fishing. The word “preservation” could be heard in both places, but in Nebraska it might refer more often to historical or cultural preservation than to the environment.

Despite the important role of hunting and fishing in how people imagined both places, there were also significant differences. I don’t remember anyone talking about birdwatching in Idaho, but it’s pretty salient in Nebraska. Because the cold winter and spring were keeping birds a bit longer than usual, we also got to see a lot of sandhill cranes in Kearney and pelicans at Harlan County Lake.

The conversations in both settings were also stamped by strong regional differences. Not surprisingly, the politics of the two large urban areas (Omaha-Lincoln and Boise) differ from the rest of the state. Each holds the state capital, several headquarters of large businesses, and each is the home of the largest university in its state. Conversations about environmental issues in the cities tended not to be much different from other US cities I know.

Outside the cities, there were obvious differences in the environmental issues salient for the Snake River region, Idaho Panhandle, and Eastern Idaho, among other regions. The Nebraska Panhandle, Central Nebraska, Niobrara River, Lake McConaughy, and Rainwater Basin stood out among the regions we discussed in Plains Safaris. Nebraska has other regions that we didn’t discuss, such as a piece of the Flint Hills. No matter the region, birds often shaped the conversations. Sandhill cranes and the Platte River, the wetland habitats of the Rainwater Basin, and the rich biodiversity of Lake McConaughy were recurring themes.

Perhaps the biggest difference between the two states is the role of the federal government. Federal lands make up almost two-thirds of Idaho, but only a little over one percent of Nebraska. As a result, you can’t talk about the environment in Idaho without talking about federal lands. In contrast, the feds were almost entirely absent from the conversations in Nebraska. State government and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) were where the action was.

The role of the federal government is particularly visible when we compare the visibility of federally-designated wilderness areas in the two states. Nebraska has only two small wilderness areas, each less than 10,000 acres. I’ve hiked near, but not actually in, each of these. They lie in lovely country, one outside Valentine and the other outside Fort Robinson. They don’t seem politically visible, and the ecotourism conference did not discuss them.

Idaho, in contrast, has 15 wilderness areas. All are big. The largest three are the Frank Church-River of No Return, at 2.4 million acres, the Selway-Bitterroot (1.3 million), and the Owyhee (1.1 million). With such “untrammeled” spaces available, wilderness is central to conversations about the environment in Idaho.

Surprisingly, there were fewer differences in the conversations about Indian Reservations. There are five reservations in Idaho, four of which have large landholdings. Nebraska has six reservations, but only two can be described as reaching a “modest” size. That count includes Pine Ridge, which has significant off-reservation landholdings in Nebraska.

The Plains Safaris organizers included two Native speakers, one of whom is a national park employee, and one non-Native who works closely with a tribe in Oklahoma. That may have made Indian Country more visible than it otherwise would have been. Those sessions were all very well attended, so there is clearly significant interest in partnering with tribes in the ecotourism sector. The NATIVE Act of 2016, which was mentioned in several presentations, will encourage such partnerships.

The role of state government in the conversation also varied considerably. Not surprisingly, both state governments support the role of the primary sectors in the state economy. In Idaho, only the difference between Boise and the rest of the state appeared in our conversations about state politics. In Nebraska, state government, fish and game, bird conservation, and tourism development were among the salient issues.

Each state has an agency in charge of tourism promotion. Not surprisingly, the themes of tourism promotion differ considerably. The Nebraska Tourism Commission cosponsored the Plains Safaris conference, so of course it was visible at the event. Its website also makes ecotourism, broadly defined, part of “The Good Life” you can experience in Nebraska. Themes such as nature, agritourism, gastronomy, adventure tourism, and outdoor recreation make up almost half of the topics on the Visit Nebraska website. I’m associated with one of these subtle glories, the Great Plains Trail. We were just featured in the June 2018 issue of Backpacker magazine – check us out here.

The Plains Safari conference also featured small-town Nebraska, reachable along scenic byways. (The Heartland Byways Conference, under the auspices of the National Scenic Byways Foundation, was held in conjunction with the main conference.) Chambers of Commerce, town governments, and other local bodies were very visible in the Nebraska conversations. Willa Cather’s fiction, grounded in small-town Nebraska, was a common point of reference.

The Idaho Division of Tourism Development emphasizes very different themes than Nebraska does. Their website stresses “Your Idaho Adventure,” and the eight themes it features all concern outdoor recreation. You have to scroll down quite a while to find the first urban theme, which is beer.

Beer also makes the Nebraska list, and I encourage my Midwest friends to explore brewpubs in Omaha. Gastronomy is also visible in Nebraska’s tourism promotion. That’s easier to sell in a diverse agricultural state than in a state with “Famous Potatoes.” That said, Boise’s restaurants do a great job featuring obscure but flavorful potato varieties.

Non-tourism businesses also made an appearance at the events I attended in each state. The J. R. Simplot Company, which commercialized french fries for McDonald’s and other retailers, is very visible downtown but did not connect to our environmental discussions. Timber company Boise-Cascade has important effects on Idaho’s forests, and was very visible.

Nebraska’s large businesses also affect the environment, of course. As a transportation company, Union Pacific is a major energy user. Because its most important freight is coal, it also contributes indirectly to coal consumption and thus to carbon emissions. However, these kinds of sustainability concerns are not visible on the ground in Nebraska. The environmental impact of “Uncle Pete” seems to be a national issue, not a local one.

My experiences in these two states made visible the highly-contextural, textured nature of environmental politics. This won’t surprise geographers and historians, but political science texts tend to focus on national politics. That means that political scientists end up focusing on pollution regulations, climate change, and things like energy policy. Those are important, but they leave out how the environment looks to people. Idaho and Nebraska illustrate how important it is to develop a nuanced understanding of how local residents see the relationship between humans and nature.

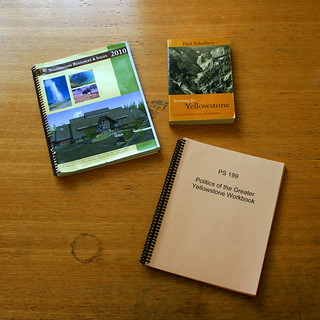

It’s also important to compare and contrast local politics and not just study a single site. That’s why I teach places like the Greater Yellowstone Area, Northwest Indiana, or the Four Corners region in my environmental politics classes.