In my opinion, one of the most interesting parts – and highly contested parts at that – of British history is the rise of Henry Tudor. I felt like the textbook did not do a great job on highlighting the multiple reasons and ways Henry Tudor legitimized his throne – understandably so, since they were for the idea that the War of the Roses was a direct aftermath of Richard II’s deposition and it would be going against that theory if they considered Henry’s win over Richard III as a conquest and not a usurpation. Although we did not spend too much time debating the legitimacy of Tudor’s rise to the throne, I would like to talk more about it here and shed some light onto his claims.

There are 3 main areas of legitimacy I will focus on in this blog: the bloodline, the conquest, and the marriage. Of course there were other factors that Henry Tudor used before and throughout his reign, but since we did get a chance to discuss most of those in class, I won’t touch on those too much.

I. The Bloodline

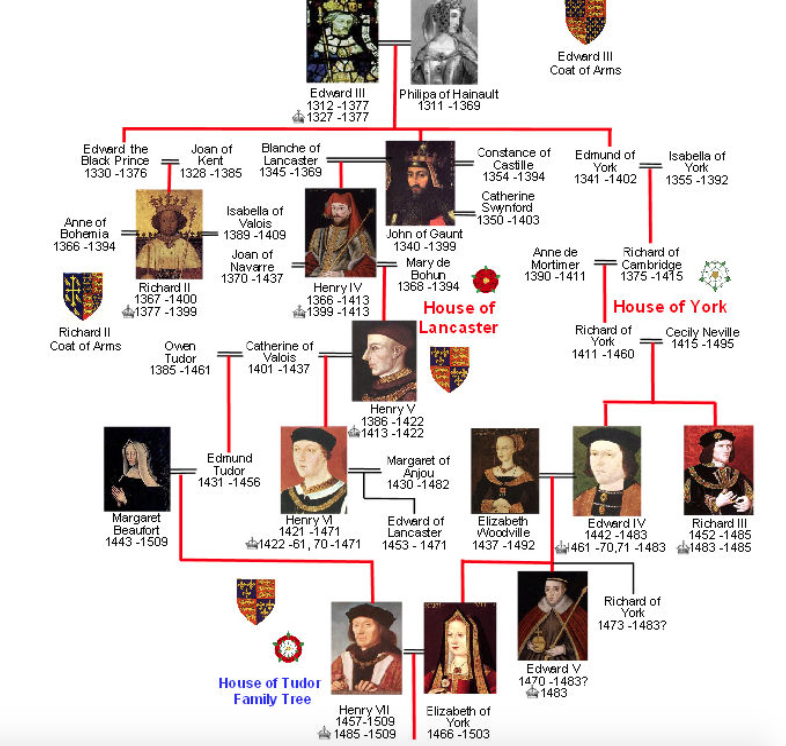

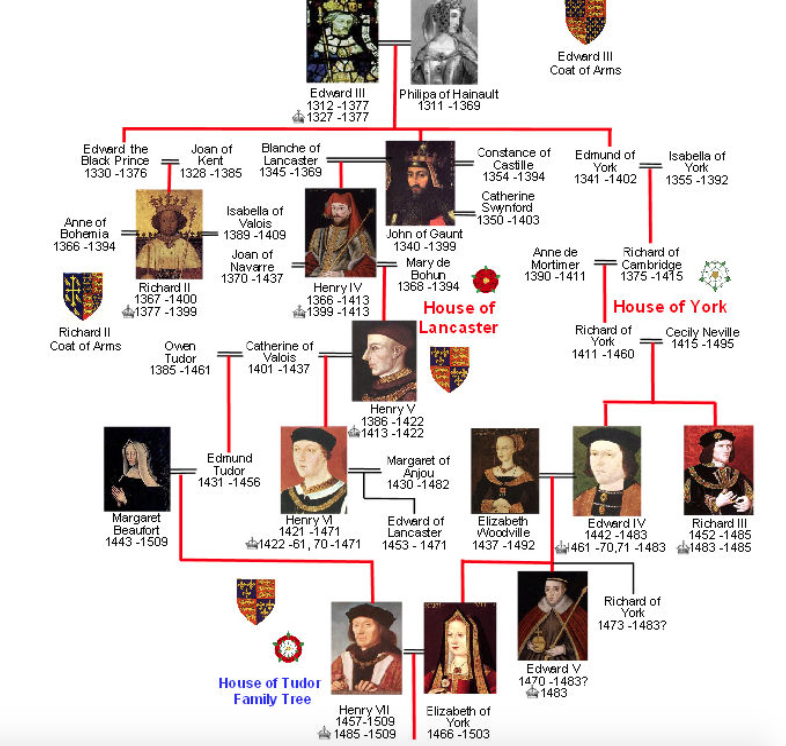

One of the reasons why it is difficult to understand the messy successions between Richard II to Henry Tudor is because one must understand the Plantagenet family tree first. So to clear that up first, let’s figure out where the Lancaster and the York branches come from first and how that adds credibility to Tudor’s claim. The Lancaster and York branches started from the third and fourth son of Edward III. John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, was the third son of Edward III, while Edmund of Langley, Duke of York, was the fourth son.

From there you can start to see some people we’ve mentioned in class before. Richard II, the famous child-king, came to the throne because he was the son of Edward III’s eldest son (his father, Edward the Black passed away before Edward III did so through primogeniture Richard II became heir). Henry of Bolingbroke, son of John of Gaunt (aka: a Lancaster), was the one usurped Richard II. The main thing to get from understanding this family tree, is that based on the order of Edward III’s children, the Lancaster branch would be considered senior to the York branch.

The Plantagenet Family Tree

Now going back to Henry Tudor and how he fits into all of this. Henry Tudor’s main blood claim was through his mother, Margaret Beaufort – heiress of the house of Beaufort. Although many claim that Henry was not of royal descent, that is technically not correct. The house (and children) of Beaufort werr legitimized as a sub-branch of the Lancaster by Richard II and Pope Boniface IX on separate occasions, after John of Gaunt and Katherine Swynford got married. This meant that John Beaufort, Henry Tudor’s maternal grandfather, was in line for the the throne after John of Gaunt’s legitimate children from his two previous marriages.

Now going past a generation, Margaret Beaufort (mother of Henry Tudor) became the head of the Beaufort house after her uncles and brothers passed away without any legitimate heirs. This is important to Henry’s claim, because after all the male Lancasters died out supporters of the branch saw the Beaufort as the successors. Therefore, in the eyes of the supporters for the Beauforts, it made sense for Henry Tudor to have a claim for the throne.

II. The Conquest

Henry Tudor supported his bloodline claim by defeating Richard III in the the Battle of Bosworth and declaring his legitimacy through right by conquest. At the time, right by conquest was still widely accepted, with the most famous example being William the Conqueror and his conquest 400 years earlier. In fact, this was a major conparison that Tudor would use to legitimize his use of force.

Some may contest to this argument by comparing it to the usurpation of Richard II by Henry of Bolingbroke. While there are many similarities to the two occurances, there are significant differences that would distinguish what is a usurpation (which is seen as unfavorable, because it would be going against the will of God) and conquest (which was been accepted centuries before).

Henry of Bolingbroke, a Lancaster, who becomes Henry IV after the deposition of Richard II

Henry Tudor, a Lancaster, who becomes Henry VII after the Battle of Bosworth

When Henry of Bolingbroke began his campaign to reclaim his father’s land (and ultimately the throne), he started with a small army that quickly grew with the support of the other barons and nobles who felt threatened by Richard II’s recent actions. When Richard II returned from Ireland, he was surprised by the Earl of Northumberland and the Archbishop of Canterbury who subsequentally imprisoned him and later deposed of him for acts against the realm. This could be considered an act of usurpation for multiple reasons. First off, many of Henry of Bolingbroke’s supporter were people of the realm. Their support and actions to help Bolingbroke would be considered treason for they were going against the king. Bolingbroke waited until Richard II was imprisoned – which happened through his supporters – to make a claim that he was next in line for the throne.The act of usurpation is the illegal taking of a position in power, so according to that definition Bolingbroke came into power through the illegal actions of his comrades that he most likely knew about – if not planned.

Secondly, there are some key elements that were missing with Henry of Bolingbroke’s campaign that would discredit it as a conquest (and showcase Henry Tudor’s success as a conquest). Although current definition may consider Bolingbroke’s action as a conquest since he did use some military force to gain control, it is unlikely this was the same definition that the people of the time were using for the word “conquest”. Looking at the most famous example of a conquest that occurred in England – the Norman Conquest – we can pick out what makes a conquest a conquest, how Henry of Bolingbroke did not conquer England (therefore making his actions and act of usurpation), and how Henry Tudor did conquer England.

The Bayeux Tapestry depicting the Battle of Hastings

In the fall of 1066, William of Normandy (aka: William the Conqueror) landed in southern England with his army, which largely consisted of soldier from all over France. He believed that the throne of England was rightfully his after Edward the Confessor promised it to him. On October 14, 1066, William’s army and King Harold’s army were in combat. The Battle of Hastings would be the battle that complete William’s conquest.Now comparing Bolingbroke’s and Tudor’s campaign to William the Conqueror’s there are two main things that makes Bolingbroke’s stand out.

First off, while Bolingbroke did initially come from France, after he was exiled by Richard II, many of his supporters (therefore his army) were from England. It was known that many of the English nobles at the time were fearful of Richard II after seeing what he had done to Bolingbroke. This is a significant difference in my opinion, because in any other context, this would be seen as a rebellion (and not a conquest) since the people of the realm were against against the current person in power, rather than an invasion by a foreign group.

Henry Tudor on the other hand, was technically not from England – he was born in Wales – and was exiled to France for a majority of his life before becoming king. Although Wales had been “fully integrated” into the domain of England by that time, the Welsh still considered themselves Celtic – therefore separate from England- in many ways. When Henry Tudor invaded England, his army consisted of French mercenaries and Welsh warriors – which could be considered a largely foreign group.

Then, there is the lack of a battle in Bolingbroke’s case. As mentioned before, Bolingbroke started moved into England when Richard II was away in Ireland. He used that time to build up his local support – and to take down any opposition – and when Richard II returned, he waited for the King to be imprisoned to make any claims. Richard II was never killed in battle. However, in the case of Henry Tudor, Tudor confronted Richard III in the Battle of Bosworth, where Richard III would be killed and Tudor would claim the throne through conquest.

While some may compare Henry Tudor’s rise to the throne to Bolingbroke’s rise, there are major differences that would distinguish the two. These differences define what is usurpation and what is conquest.

III. Marriage

Even after defeating Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth, Henry Tudor’s reign was questioned. The Lancaster and York claims have been muddled for years and Tudor’s blood claim was considered dubious, because it was through his mother. After taking the throne, Tudor solidified his rule by marrying Elizabeth of York. This effectively ended the War of the Roses for now the most senior of the Lancaster and the York lines were a part have converged through Henry and Elizabeth’s children.

-

Portrait of Elizabeth of York holding the white rose of York

How did Elizabeth of York become the most senior person of the York branch? Well, after the Battle of Bosworth the Plantagenet were in the same situation that the Lancaster branch had to deal with before, there were no living male descendants except for the Earl of Warwick who was just a child (and who would soon be imprisoned by Henry Tudor). So as the eldest daughter of Edward IV (the elder brother of Richard III) with no surviving brothers, Elizabeth was at the top of the Yorkist line.

Although Henry Tudor did not claim the right to rule through his wife, it was important that he was married to Elizabeth of York. One reason is that it severely weakened the claims of any remaining Yorkists, for there is no longer a possibility of someone using the argument of right to rule through marriage to Elizabeth of York (as some may remember from class, it was assumed that Richard III was planning to marry Elizabeth of York to solidify his own reign). Claiming right through the female line would have been possible, since that was what Richard of York unsuccessfully attempted to do, but did work for Edward IV. This, of course, also resonates with Henry Tudor’s own blood claims. Another, and probably most important, reason for the union of the two branches is to secure his children’s future. His children would now have the biggest claim to the English throne, having a connection from both sides of the family.

-

Creation of the Tudor Rose which was used through the Tudor period

It was obvious that after the marriage of Henry Tudor and Elizabeth of York, there was very little for his opponents to go off of. Very few had a better claim than Henry Tudor. Two major threats of pro-Yorkist rebellions were based off of some unknown pretending to be the Earl of Warwick (who was imprisoned) or as the younger brother of Elizabeth of York (one of the boys from the Tower of London myth). Therefore, it could be said that by this point, Henry Tudor was there to stay.

Henry Tudor’s Coat of Arms: (left) the mythical Welsh dragon and (right) the white greyhound of Richmond

After the Deposition of Richard II, the Plantagenet line of succession became harder and harder to understand. However, when Henry Tudor made his claim and rose to the throne, he made sure he was the rightful ruler in every way he could. In fact, when he got married to Elizabeth of York in January of 1486, the Bull of Pope Innocent VIII officially recognized the marriage between the two families, Henry Tudor’s right to rule England, and the line of succession continuing with his children. And all of those who opposed would then be excommunicated from The Church. The religious and international implications of the papal bull had put the metaphorical nail on the coffin to the dispute started years before. Henry Tudor successfully took over England, and his children would continue to rule for many years to come.

Well after 2 days and many drafts later, that is all I have to say on this topic. If anyone would like to discuss more about it, please do comment. It was very interesting to write this all out, so I would love to hear what your thoughts are on the topic!