Echoes of the Past at the Manzanar War Relocation Camp

by Jon Sweitzer Lamme, photos by Siobhan McKissic

It is taken as settled in Western preservation practice that whatever is available to be preserved is all that should be preserved—there should not be an effort to “restore” or re-create what has been lost—and that we should preserve all that we have—nothing should be removed or replaced once something has come under the care of preservationists. However, this attitude is not universal. In Japan, for example, temples are regularly demolished and reconstructed with new, identical materials—it is the sacredness of the space that is important to be preserved, rather than the physical materials used to create that space.

It is taken as settled in Western preservation practice that whatever is available to be preserved is all that should be preserved—there should not be an effort to “restore” or re-create what has been lost—and that we should preserve all that we have—nothing should be removed or replaced once something has come under the care of preservationists. However, this attitude is not universal. In Japan, for example, temples are regularly demolished and reconstructed with new, identical materials—it is the sacredness of the space that is important to be preserved, rather than the physical materials used to create that space.

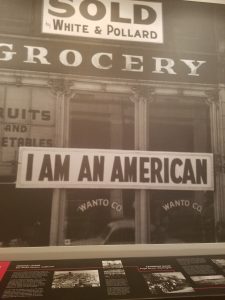

Manzanar War Relocation Camp is located in eastern foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains in California. Over 10,000 Japanese-Americans, including US citizens and children, were moved from their homes on the West Coast to this camp during World War II—some of the 150,000 who were moved to dozens of these camps across the country without due process, simply because of their heritage. After the war, the camp was abandoned, and the wooden shacks built for the internees were allowed to be destroyed by the elements and scavenged.

After a concerted effort in the 1960s, the National Park Service began work on creating a National Historic Site on the spot where the camp stood. In consultation with survivors of the camps, they came up with a preservation solution that works with both Japanese and Western notions of preservation. The site works to emphasize the lived experiences of the internees—to preserve the sense of the space, rather than the missing buildings. This means that a few of the buildings have been reconstructed, with period-appropriate but not original furnishings, to allow visitors to enter and look around, gaining a feeling for life in these small, minimally-furnished tarpaper shacks in the middle of the desert.

After a concerted effort in the 1960s, the National Park Service began work on creating a National Historic Site on the spot where the camp stood. In consultation with survivors of the camps, they came up with a preservation solution that works with both Japanese and Western notions of preservation. The site works to emphasize the lived experiences of the internees—to preserve the sense of the space, rather than the missing buildings. This means that a few of the buildings have been reconstructed, with period-appropriate but not original furnishings, to allow visitors to enter and look around, gaining a feeling for life in these small, minimally-furnished tarpaper shacks in the middle of the desert.

Choices made in the reconstruction point to another important concept in preservation: the idea of the period of significance. Many artifacts go through layers of use, changing form each time. Preservationists must decide what period is most important to be preserved and shown to the public. In this case, the shacks were shown at their bleakest, with holes in the walls and floor, and only a layer of wood and tarpaper separating the residents from the harsh winds that sweep the area. This was their first iteration; as winter came about nine months later, the US military provided the residents with drywall and linoleum to keep the worst of the cold out.

Preservationists in the National Park Service took a Japanese approach to presenting the site to visitors: they chose to focus on preserving the emotions created by life in the camp, rather than the camp itself. For most of their time there, the huts were better than they are displayed to visitors. However, most of the oral histories given by former residents focused on that initial period, in the tarpaper huts.

Preservationists in the National Park Service took a Japanese approach to presenting the site to visitors: they chose to focus on preserving the emotions created by life in the camp, rather than the camp itself. For most of their time there, the huts were better than they are displayed to visitors. However, most of the oral histories given by former residents focused on that initial period, in the tarpaper huts.

Other parts of the camp that were reconstructed were the parts that evoked the strongest emotional reactions: the toilets, which were an open line of undivided pits; the watchtower, where soldiers with machine guns and spotlights stood guard day and night; the baseball field, constructed from scrap wood and dead trees to provide a semblance of normalcy to children.

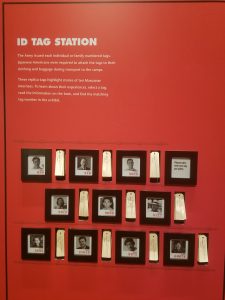

The rest of the site is left bare, except for the barbed wire fence that surrounded the entire compound, and the stone buildings, including a marker for the cemetery, which was constructed by an interned stonemason. Archaeological evidence from excavation of certain areas of the grounds, preserved through standard Western practices, contributes to interpretation indoors, as well.

The rest of the site is left bare, except for the barbed wire fence that surrounded the entire compound, and the stone buildings, including a marker for the cemetery, which was constructed by an interned stonemason. Archaeological evidence from excavation of certain areas of the grounds, preserved through standard Western practices, contributes to interpretation indoors, as well.

This combination of Japanese and Western practices, aimed at the goal of preserving the “feeling” of a place, rather than simply the artifacts in a place, leads to a much greater understanding of the horrors of Manzanar for visitors.