Written by Fiona Hartley-Kroeger, GA

Romance novels have changed a lot since Janice Radway’s landmark scholarly work, Reading the Romance, first published in 1984. For one thing, they’re not just about straight white women finding fulfilment under the patriarchy. (That’s never been all that romance novels have been about.) In their exploration of many kinds of love between many kinds of people, today’s romance novels create precisely what Radway hoped for: “a place and a vocabulary with which to carry on a conversation about the meaning of…personal relations and the seemingly endless renewal of their primacy” (18). Romance is a beautiful, varied bouquet.

As the recent “romantasy” trend demonstrates, romantic plotlines and relationships are frequently central to works in other genres. Romance elements can be integral to works of literary fiction, science fiction, fantasy, mystery, horror, and much more.

In celebration of this versatile, ever-evolving genre, here are some recent favorites:

ROSES

These novels participate in the genres of contemporary and historical romance, with strong attention to diversity and thoughtful reflection on how they distinguish themselves from their more homogenous predecessors. HEA (Happily Ever After), of course, guaranteed!

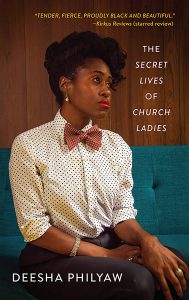

Ashley Herring Blake, Delilah Green Doesn’t Care

Ashley Herring Blake, Delilah Green Doesn’t Care

Suuuuuuure she doesn’t. Photographer Delilah Green is on the cusp of making it in New York City, with a string of pleasant one-night stands and an invitation to participate in a gallery show. Unfortunately, she’s also agreed to photograph her stepsister’s wedding in small-town Oregon. A reluctant trip to her childhood hometown unearths a wealth of complicated relationships and family hurt, but also brings the possibility of new beginnings.

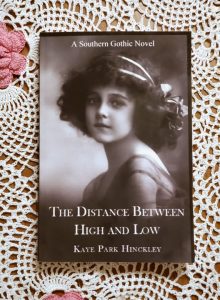

Alyssa Cole, A Princess in Theory

Alyssa Cole, A Princess in Theory

Struggling epidemiology grad student Naledi is pretty sure the emails she keeps getting are unusually persistent scams. After all, what are the odds that she’s actually the long-lost betrothed of Prince Thabiso? When Thabiso shows up in New York and in her life, though, things get interesting. As a Black woman in STEM trying to get through grad school and pay off her student loans, Naledi is an instantly sympathetic heroine; the realities of her chosen path initially clash with Thabiso’s over-privileged lifestyle in a way that’s both serious and funny. His journey toward understanding her is by turns humorous and touching, and the whole thing is incredibly fun with, of course, a sweet, solid emotional core.

Sonali Dev, Recipe for Persuasion

Sonali Dev, Recipe for Persuasion

Jane Austen meets cooking competition (Dancing with the Stars-syle) in this second entry in Sonali Dev’s series about an overachieving Indian family living in California. (Don’t worry if you haven’t read the first book, Pride, Prejudice, and Other Flavors, though you should give that a try too!) In a twist on my favorite Jane Austen novel, Persuasion, chef Ashna Raje and her former first love, soccer star Rico Silva, are paired on a high-stakes cooking competition. Their dynamic is as delicious as the food they prepare while utterly failing to resist their feelings. This is a wonderfully flavorful novel about first love, second chances, complicated families, and—inevitably—cooking puns.

Alexis Hall, A Lady for a Duke

Alexis Hall, A Lady for a Duke

The traditional concerns of the classic Regency romance novel—personal autonomy, gendered social roles, issues of class, childhood trauma, and transformation through love—provide an ideal framework for a story about a trans heroine and her childhood best friend. Viola Carroll, presumed dead on the battlefield in France, has sacrificed a great deal to become her true self. Her childhood best friend, Gracewood, never recovered from her death. When they meet again, they both have a LOT of baggage to work through—but they do so thoughtfully and oh-so-tenderly, with a few (minimal) misunderstandings and a really lovely mood of trans affirmation throughout.

Courtney Milan, The Duke Who Didn’t

Courtney Milan, The Duke Who Didn’t

You’ll fall in love with the entire village of Wedgeford, something of a haven for members of the Chinese diaspora in rural Victorian England. In this series-starter, longtime villager Chloe Fong and half-Chinese, half-English nobleman Jeremy Wentworth navigate their feelings amid quaint village shenanigans. Chloe is Organized! Her prized possession is a clipboard! She WILL make a commercial success of her father’s new culinary concoction, a sauce of supreme savor! Jeremy is more complex than his jokester persona would have you think, but he’s genuinely a sunshiny, sweet man who maaaayyy have forgotten to mention one tiny detail about his identity. Oops? They’re adorable.

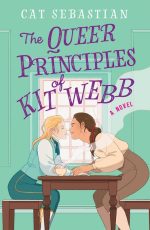

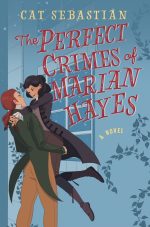

Cat Sebastian, The Queer Principles of Kit Webb & The Perfect Crimes of Marian Hayes

Cat Sebastian brings Georgian England to queer romance! Enter a world of highwaymen, coffee houses, and incredible fashion. The first book features a banter-filled romance between ex-highwayman Kit Webb and nobleman Percy, Lord Holland; the second stars Percy’s best friend/stepmother/bi icon Marian Hayes and idealistic Rob Brooks, Kit’s former partner in (literal) crime. Cuteness! Crimes! Coffee!

Further Rosy Reading:

Jane Austen, Persuasion

K.J. Charles, The Secret Lives of Country Gentlemen & A Nobleman’s Guide to Seducing a Scoundrel

Emily Henry, Book Lovers

Georgette Heyer, Lady of Quality

THORNS

Here, the HEA is…less guaranteed. These novels hail from a variety of other genres and draw on romance tropes, comment on romantic fiction expectations, or focus less on the HEA than on the sometimes painful process of navigating feelings and relationships (or, you know, saving the world).

Akwaeke Emezi, You Made a Fool of Death with Your Beauty

Akwaeke Emezi, You Made a Fool of Death with Your Beauty

The line between genre and literary fiction is frequently a thin one, revealing more about publishing norms and audience expectations (or prejudices) than about a work’s narrative, stylistic, or thematic content. In this novel, published as literary fiction, sex and grief collide as Feyi fights a messy, utterly necessary battle to recover from a shocking loss and rediscover love.

Intisar Khanani, Thorn

Intisar Khanani, Thorn

This is a lovely, fleshed-out retelling of the Brothers Grimm tale “The Goose Girl.” The unpleasant bits (identity theft, talking severed horse heads) are thoughtfully elaborated, and what begins as a tale of escaping abuse and betrayal gradually develops into a heart-tugging love story.

T. Kingfisher, Nettle & Bone

T. Kingfisher, Nettle & Bone

This is not a novel where the princess marries the prince and lives happily ever after. Actually, the prince murders one sister, abuses another, and deserves what’s coming to him when Princess Marra decides to take him down. There IS a cute romance, though, amid Marra’s efforts to complete impossible tasks, gather allies, and figure out how to murder the man she’s next in line to marry. (Maybe two cute romances, if you squint.) This is a perfectly dark fairy tale with all the unpleasant sorcery and underground tomb mazes you could wish for.

Tamsyn Muir, Gideon the Ninth

Tamsyn Muir, Gideon the Ninth

“Lesbian necromancers in space” isn’t INACCURATE, per se, but that description doesn’t do justice to Muir’s tangled web of love, grief, mental instability, and space palaces. The necromantic lesbians are cute, sure (by some definitions), but there’s a whole buffet of other relationships running the gamut from the wholesome to the wildly disturbing, and they’re all DELICIOUS.

Emily Tesh, Silver in the Wood & Drowned Country (coming soon!)

Emily Tesh, Silver in the Wood & Drowned Country (coming soon!)

If sheer sweetness was the only criterion, these two novellas could go under Roses, but the HEA is by no means guaranteed. Tobias, the Wild Man of Greenhollow, and Henry Silver, newly arrived owner of Greenhollow Manor, undergo horror-filled trials of the heart to be together—only to undergo an acrimonious breakup that precipitates the second volume. Twining around their relationship are wonderful elements of English fairy lore; this is a great choice for fans of Susanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell who would prefer something a little shorter.

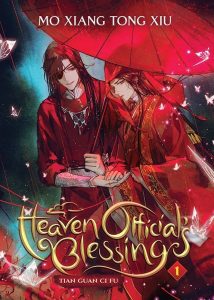

Mo Xiang Tong Xiu, Heaven Official’s Blessing: Tian Guan Ci Fu (coming soon!)

Mo Xiang Tong Xiu, Heaven Official’s Blessing: Tian Guan Ci Fu (coming soon!)

An exemplar of the Chinese danmei (boys’ love) genre by the author of The Grandmaster of Demonic Cultivation: Mo Dao Zu Shi (the novel on which the 2019 drama The Untamed is based). The romance between a god and a ghost is incredibly sweet; it’s everything else that’s thorny! The epic tale spans 800 years, three realms, an extensive, memorable cast, martial arts, and a love story of unmatched devotion. This is the officially licensed English translation. Coming soon!

Further Thorny Reading:

Emily Brontë, Wuthering Heights

Angela Carter, The Bloody Chamber

Freya Marske, A Marvellous Light & A Restless Truth (A Power Unbound coming soon!)

Silvia Moreno-Garcia, Gods of Jade & Shadow

Did you know? We also have a selection of romance on audiobook!

Open City

Open City Quartet

Quartet Mrs. Dalloway

Mrs. Dalloway NW

NW French Milk

French Milk Taipei

Taipei