What’s on your to-read list?

If you’re anything like us, your to-read list is ever-expanding, as exciting new books jump the queue over hulking classics you’re a little embarrassed you haven’t read by now.

The internet is replete with articles like “Classic Novels Everyone Should Read” and “30 Classics You Should Read Before You Die.” These lists are populated by novels like Great Expectations, Moby Dick, and Animal Farm. Intimidating lists like these can discourage even the most intrepid reader.

Some people give up on the classics before they’ve truly started them, intimidated by their length or density. Others are skeptical of their relevance to modern life. Many more simply lack the time and energy to wade through “the great books.”

But while there is no required reading list for life, who among us would not like to know these classics? Or at least know them well enough to understand what’s so very “great” about them?

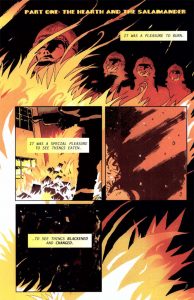

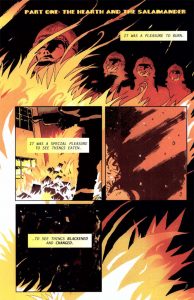

A page from Tim Hamilton’s graphic adaption of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451

This is where the graphic adaptation comes in. This increasingly popular format blends words, panels, and illustrations to create a highly readable and accessible new work. Some of these graphic interpretations are so innovative and beautiful they could qualify as literary masterpieces in their own right.

A quick internet search will reveal that an astonishing number of literary classics have been adapted in this way. Everything from The Great Gatsby to Paradise Lost to The Stranger has received the graphic novel treatment.

And why not? Because they distill stories into essential dialogue and visuals, graphic novels are quick reads. They can thus provide fascinating introductions to topics, ideas, and even genres of literature a reader might have otherwise discounted as out of reach. In this way, a graphic adaptation can provide a point of entry to a whole new world of stories.

Have you read any great graphic adaptations of literary classics? If not, we’ve included 3 of our favorites below to help you get you started.

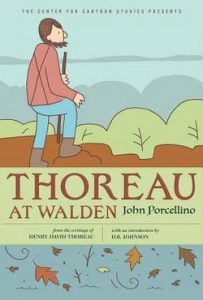

Thoreau at Walden, adapted by John Porcellino

Each artist has their own interpretation of the text, and some books are more suited to the graphic treatment than others. As in any adaptation, sometimes sacrifices have to be made to fit the new format.

John Porcellino’s Thoreau at Walden, for example, distills Henry David Thoreau’s sojourn at Walden Pond into its most essential lessons, telling the rest of the story through deceptively simple illustrations.

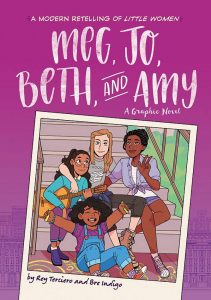

Meg, Jo Beth, and Amy, adapted by Rey Terciero and Bre Indigo

Some artists use graphic adaptations to put a modern spin on a much-beloved classic. Jo, Beth, Meg and Amy, for example, reimagines the March sisters as part of a multi-ethnic blended family coming up, and coming out, in modern-day New York City. It’s hard to imagine, Louisa May Alcott, a staunch abolitionist and feminist, would object to this adaptation of Little Women.

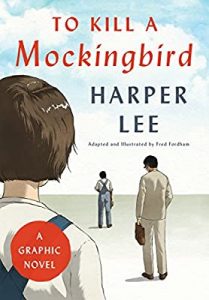

To Kill A Mockingbird, adapted by Fred Fordham

In 2018, PBS launched an eight-part series called The Great American Read. The series was designed to get Americans reading and talking passionately about books, and encouraged viewers to cast their votes in determining America’s top 100 best-loved novels. The results were a fascinating mix of classic and modern titles included on many people’s to-read lists.

But America’s number one best-loved novel proved to be Harper Lee’s To Kill A Mockingbird, a coming-of-age story told against the backdrop of simmering racial tensions in small town Alabama. If this classic is on your to-read list, check out Fred Fordham’s graphic adaptation, available in the Literatures and Languages Library’s very own collection.

For today’s celebration of National Poetry Month, Isaac Willis, a student in UIUC’s Creative Writing MFA program, reads Jericho Brown’s “Say Thank You Say I’m Sorry.”

For today’s celebration of National Poetry Month, Isaac Willis, a student in UIUC’s Creative Writing MFA program, reads Jericho Brown’s “Say Thank You Say I’m Sorry.”

Christopher Kempf is Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of English, where he teaches in the MFA Program. He is the author of the poetry collections

Christopher Kempf is Visiting Assistant Professor in the Department of English, where he teaches in the MFA Program. He is the author of the poetry collections