Illinois history is filled with tragic, extraordinary, and disastrous events. Our state has seen tornadoes, fires, mining disasters, riots, epidemics and many other catastrophic happenings that have shaped its history. From infamous disasters like the Great Chicago Fire to lesser-known tragedies like the Cherry Mine Disaster, each of the events featured in this exhibit has had a great impact on the state and its communities.

The items on display in this exhibit span two hundred years of Illinois history and highlight some of the most devastating events from our state’s past. The firsthand accounts, contemporary photographs, and newspaper articles on display here show how tragedies have shaped the lives of many ordinary Illinois citizens.

1864-1909

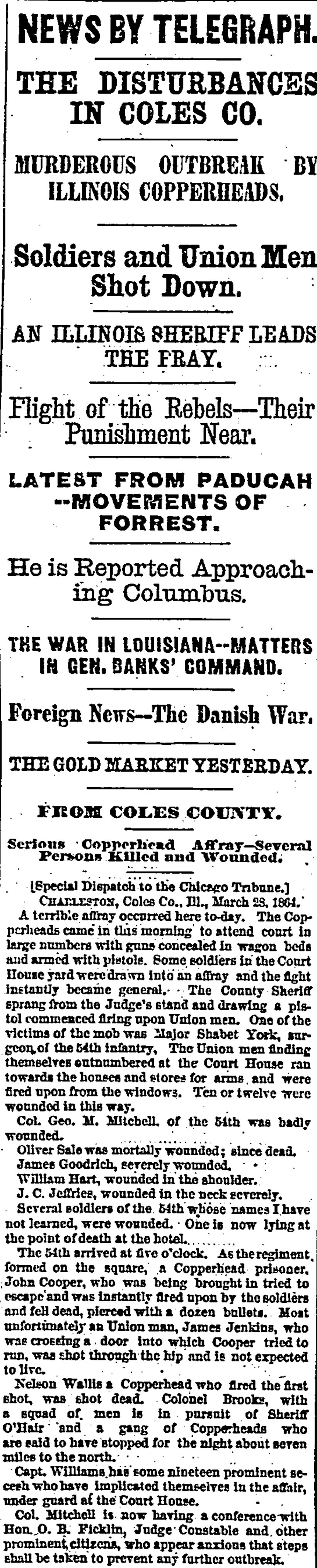

Charleston Riot – 1864

Like many towns around the country during the Civil War, the city of Charleston, Illinois, was divided by the country’s ongoing conflict. This division led to bloodshed in Charleston on March 28, 1864, when an altercation broke out between anti-war Democrats (also known as “Copperheads”) and Union soldiers who were home on leave. Shooting erupted on the courthouse square, and at least nine men were killed, with twelve more wounded. One of the deadliest civilian incidents during the war, the riot made national headlines as a visible example of anti-war sentiment.

The deaths turned public opinion, especially in Illinois, against “Copperheads” and other anti-war groups. Many of those involved in the riot fled the state or went into hiding. Twenty-nine men were eventually captured, but all were either released or exonerated by the end of 1864.

Item 3: Chicago Daily Tribune article on Charleston Riot, March 30, 1864, Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress.

The Great Chicago Fire – 1871

In 1871, Chicago was the fastest growing city in the United States. Because the city’s new buildings were often constructed poorly and with flammable materials, fires were common. The Great Fire began on the west side of the city around 9:00 p.m. on Sunday, October 8, 1871. With the aid of a strong prairie wind and an exceptionally dry summer and fall, the fire grew rapidly. Firefighters were slow to respond, and as dozens of locations burned at once, they struggled to gain control of the fire. On the morning of the 10th, a rainstorm extinguished the last of the flames. By that time, 1,687 acres had been destroyed. Three hundred people died, and 100,000—about a third of the city’s population—lost their homes.

Item 4: Foster, Thomas D. A Letter from the Fire, privately printed, 1923. Illinois History and Lincoln Collections. (Click on image above to view Flip Book of full text on the Internet Archive.)

A Letter from the Fire is a published edition of a letter written by Thomas D. Foster to his family in the weeks after the fire. At the time of the fire Foster was 24 years old; he had arrived in Chicago in September of 1871 from London, Canada. His family printed copies of the letter to share with friends and neighbors.

Item 5: Illustration of the burning of Crosby’s Opera House, 1871. Harper’s Weekly, October 28, 1871. Reprinted in Lowe, David, The Great Chicago Fire, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. 1979. Illinois History and Lincoln Collections.

The Crosby Opera House was one of the many grand Chicago buildings destroyed in the Great Fire.

Cherry Mine Disaster – 1909

Between the years of 1905 and 1930, about 2,000 coal miners died on the job every year in the United States.

On Saturday, November 13, 1909, in a coal mine in Cherry, Illinois, a cart filled with hay collided with a kerosene lamp and caught on fire. About 200 men managed to escape initially, but ultimately 259 people died in the tragedy, including four boys under the age of 16. Twenty-one men remained trapped in the mine for a week before being rescued. During the final rescue mission there was a miscommunication between the rescue party and those on the surface, and all twelve of the people coming up—both trapped miners and their rescuers—died. This was the third most deadly coal mining disaster in American history. The Cherry Mine Disaster drew national attention to issues of mine safety and child labor.

The photographs featured depict the aftermath of the disaster.

Item 1: Photograph of bodies being identified after Cherry Mine Disaster, 1909. Box 2, Edward Caldwell Cherry Mine Disaster Research Collection (MS 515), Illinois History and Lincoln Collections.

Item 2: Photograph of scene at Cherry Mine Disaster, 1909. Box 2, Edward Caldwell Cherry Mine Disaster Research Collection (MS 515), Illinois History and Lincoln Collections.

1915-1925

Eastland Disaster – 1915

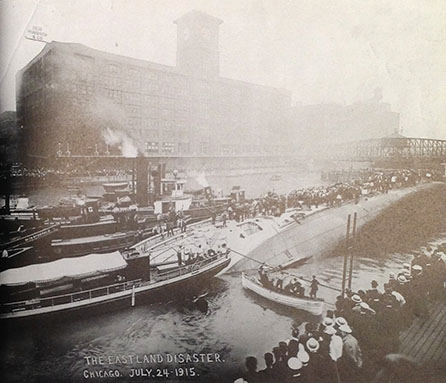

On July 24, 1915, thousands of employees of the Western Electric Company and their families gathered in Chicago to board ships to attend the annual company picnic. The first ship to depart, the S.S. Eastland, began boarding early that morning. The annual outing quickly turned tragic as the Eastland began to list back and forth in the Chicago River and then rolled onto its side with 2,500 passengers aboard. Within minutes, nearly 850 people had drowned or suffocated, and many others were injured or trapped inside the ship. Most of the victims were under the age of 25. The Eastland disaster was the third deadliest peacetime maritime catastrophe.

Item 1: Photograph of the SS Eastland capsized in the Chicago River, July 24, 1915. Reprinted in Wachholz, Ted, , Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2005. Illinois History and Lincoln Collections.

The Eastland capsized in the Chicago River, near Clark Street. As survivors climbed out of the water, they huddled on the side of the overturned ship for safety. After the disaster, other nearby ships came to the Eastland‘s aid, including ships that had been standing by to take other Western Electric Company employees to their annual picnic. Rescue operations lasted all day, and huge crowds of onlookers came to the scene.

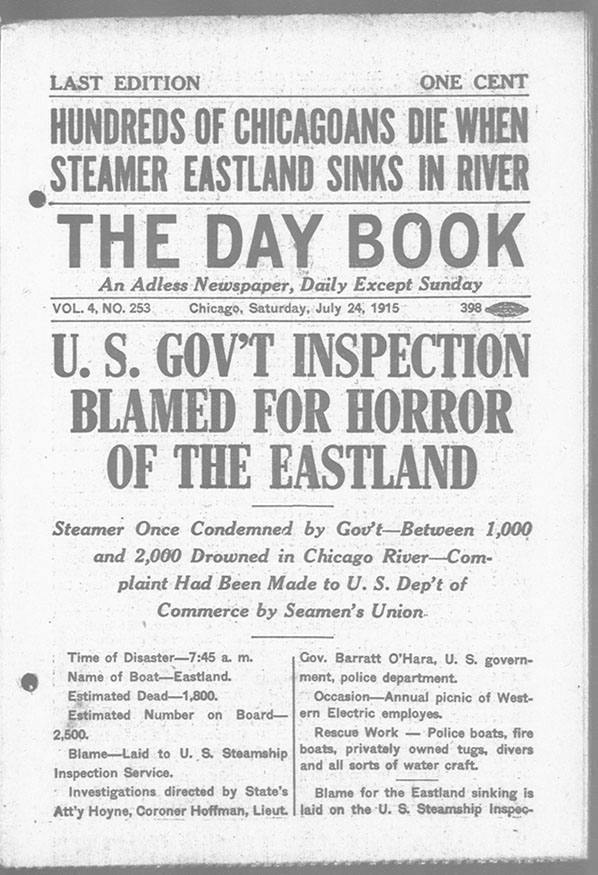

Item 2: The (Chicago) Day Book article on the Eastland Disaster, July 24, 1915. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers, Library of Congress.

Newspapers in Chicago and around the nation were quick to report on the ship’s sinking. The total of estimated dead was hugely inflated from the actual number, likely due to the chaos and uncertainty as to who had been aboard and where they had gone after the disaster. Debate raged over who ought to take responsibility for the tragedy, but in the end no one was ever formally held accountable.

“Spanish Flu” Pandemic – 1918-1919

The influenza pandemic that broke out during the final year of World War I resulted in global devastation. The worst strain of the disease first emerged in Boston in August 1918 and subsequently spread across the United States, ultimately claiming the lives of an estimated 650,000 Americans. The city of Chicago saw 38,000 cases of influenza and 13,000 cases of pneumonia related to the pandemic,

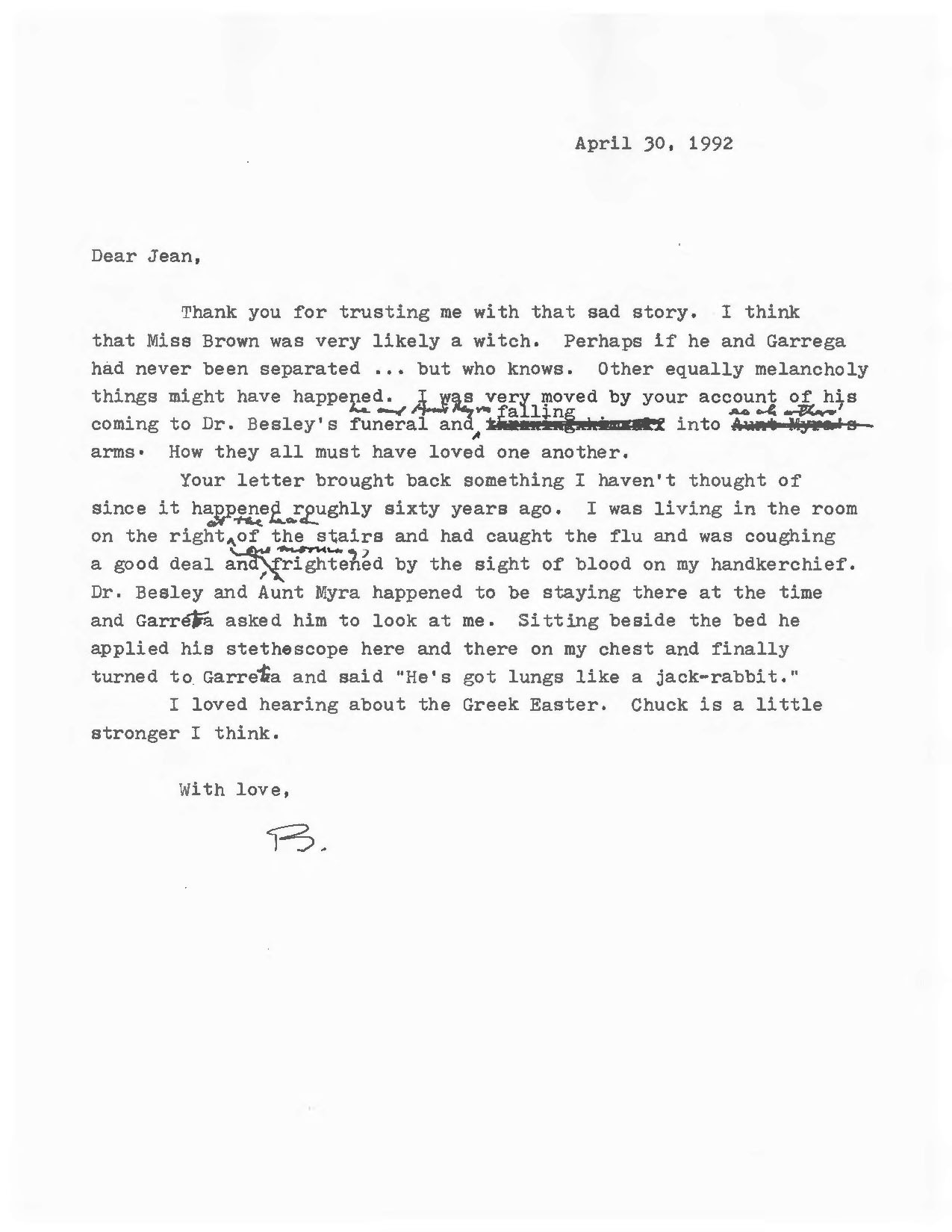

In Lincoln, Illinois, William Maxwell, who would eventually become a well-known author, came down with the virus on December 24, 1918, at the age of ten. He still recalled the illness vividly decades later when he wrote of his experience in a letter to Jean Yntema, “I…had caught the flu and was coughing a good deal and frightened by the sight of blood on my handkerchief.”

Item 3: Letter from William Maxwell to regarding 1918 flu pandemic, April 30, 1992. Box 7, Busey-Yntema Collection (MS 989), Illinois History and Lincoln Collections. Note: This letter is under copyright.

William Maxwell (1908-2000) was staying with his aunt in Lincoln, Illinois, when he contracted the flu in December 1918. Maxwell’s experience with the flu, his mother’s passing due to complications from the disease, and other memories of his youth fueled his work as a writer. This is seen particularly in his novels, including They Came Like Swallows and So Long, See You Tomorrow.

Tri-State Tornado – 1925

Illinois experienced the deadliest tornado in U.S. history when it was hit by the Tri-State Tornado of 1925. This tornado began on March 18, 1925, in southeastern Missouri and stayed on the ground for 3 ½ hours. It traveled a 219 mile path through Missouri, Illinois, and Indiana with a forward speed of 56-73 miles per hour and winds reaching 300 miles per hour. 695 people died and 2,027 people were injured. Illinois was the most heavily hit of the three states with 613 deaths—the largest death toll caused by any tornadic event in a single U.S. state.

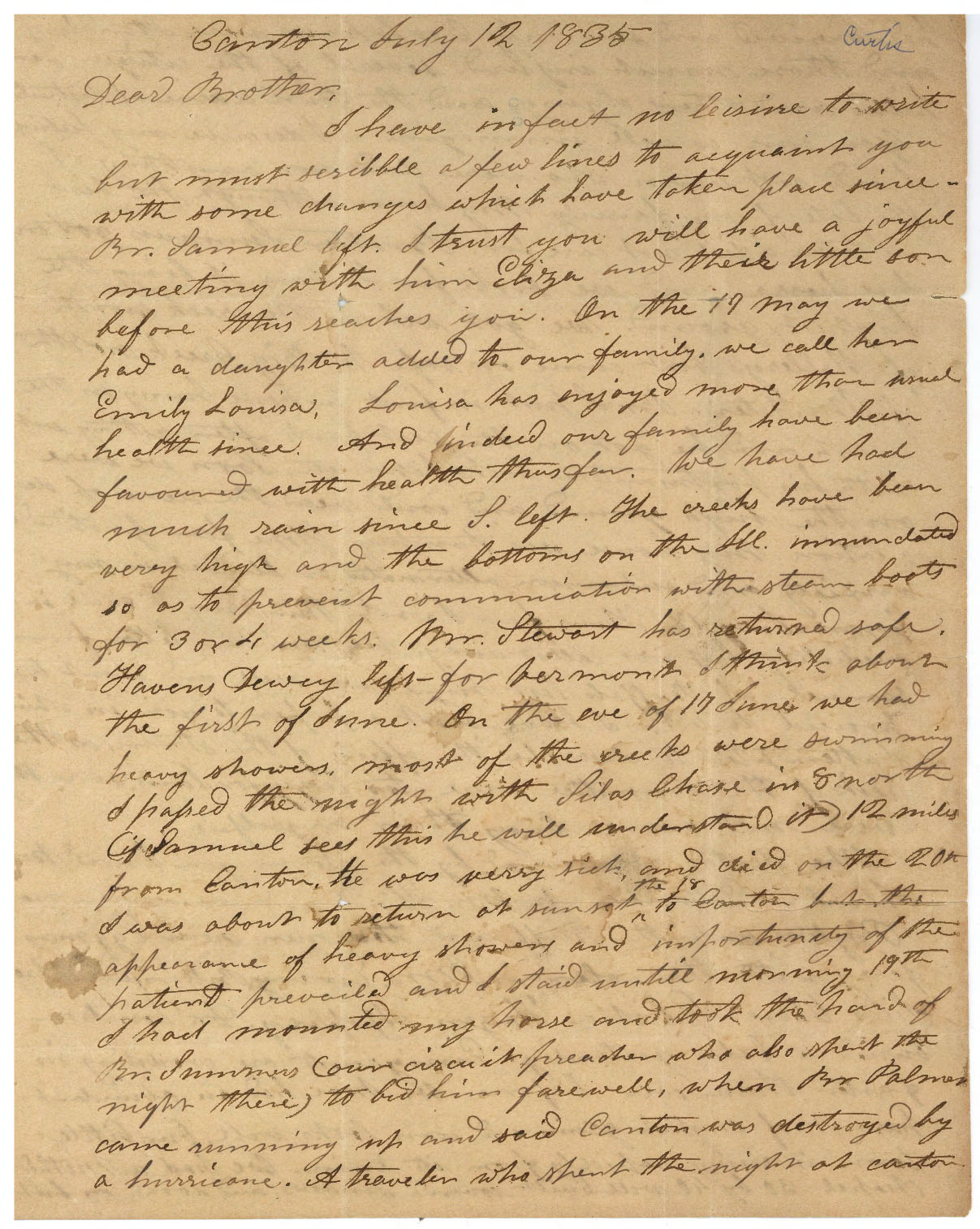

Item 4: Letter from Rev. Lathrop Curtis to Rev. Otis Curtis regarding a tornado that hit Canton, Illinois, July 12, 1835. Lathrop W. Curtis Letter (MS 068), Illinois History and Lincoln Collections.

Tornados have been a part of life in Illinois throughout history of the state. This 1835 letter from Lathrop W. Curtis details a tornado that ripped through Canton, Illinois, and the damage it caused to homes and farms in the area.

Item 5: Photo of aftermath of the Tri-State Tornado, 1925. Reprinted in Akin, Wallace, The Forgotten Storm: The Tri-State Tornado of 1925, Guilford: The Lyons Press, 2002. Illinois History and Lincoln Collections.

The image above depicts the destruction caused by the Tri-State Tornado in Murphysboro, Illinois. The storm left destruction in several Illinois towns, and Murphysboro saw the highest number of casualties, with over 200 people killed. The tornado destroyed around 15,000 homes and in Illinois it caused roughly $10 million in property damage.