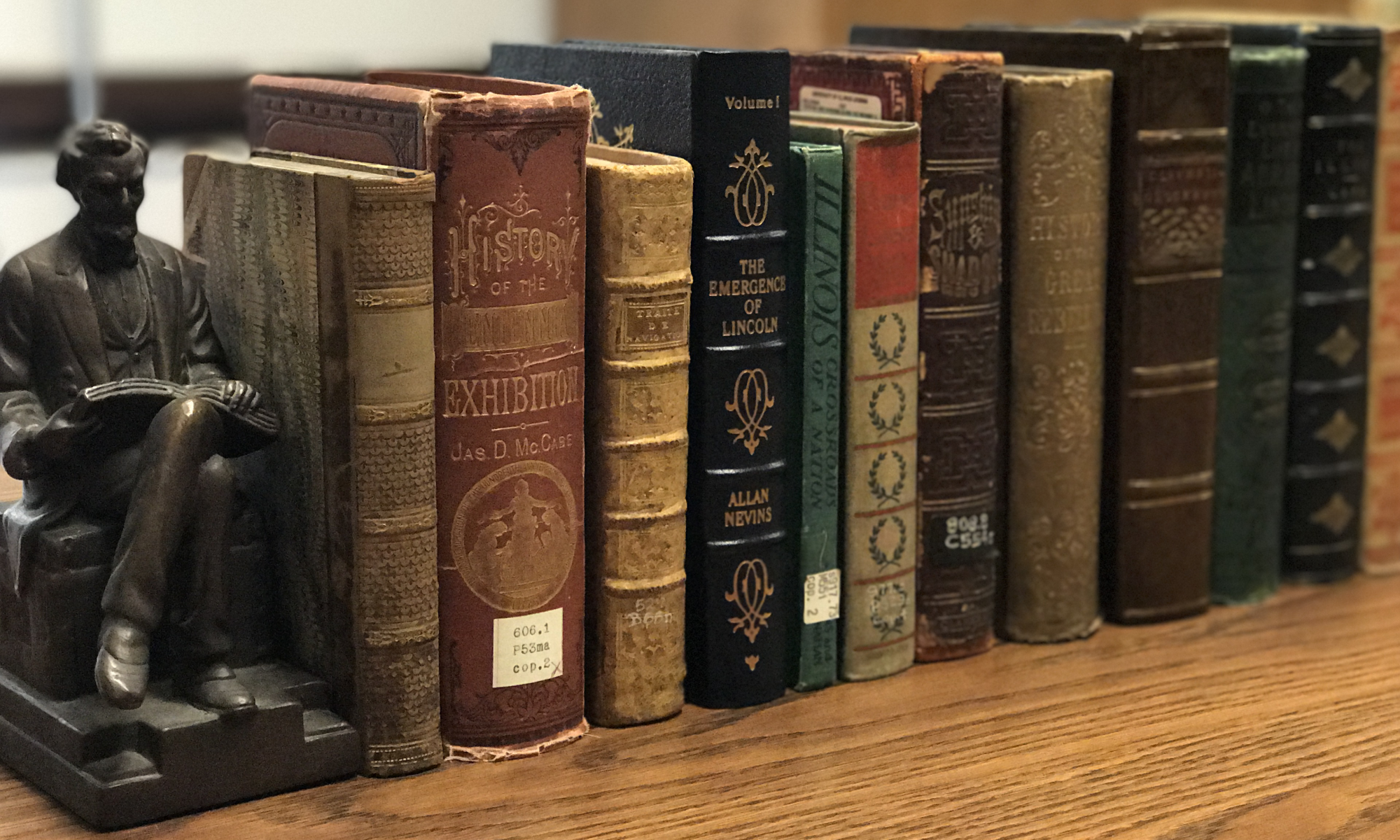

“Here I Have Lived”: Recreating the Land of Lincoln

Drive along any road leading into our state and you will be greeted with a green sign welcoming you to the “Land of Lincoln.” This moniker has become ubiquitous in Illinois, reflecting the state’s heritage as the place that Abraham Lincoln called home from 1830 to 1861, starting as an impoverished flatboat crewman and leaving as the nation’s President-Elect.

Yet the actual lands on which Lincoln lived and worked have changed considerably. Far from being static portals into the past, the natural and built environments that Lincoln knew were altered, updated, and even outright destroyed over time. This exhibit uses the histories of two of those sites, Lincoln’s New Salem State Historic Site and Lincoln Home National Historic Site, as windows into the ways Illinoisans have since sought to restore and recreate the lands of Lincoln.

Download the exhibit booklet to learn more about the items displayed.

Case 1

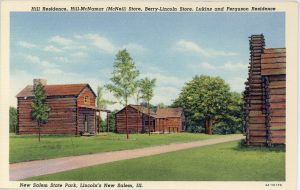

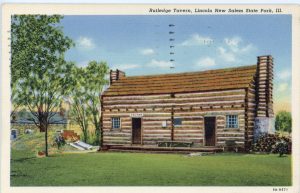

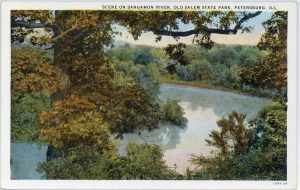

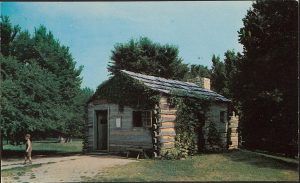

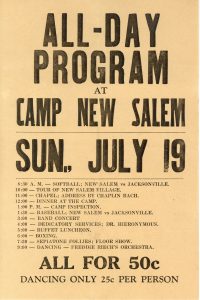

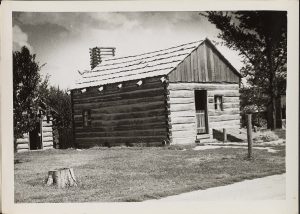

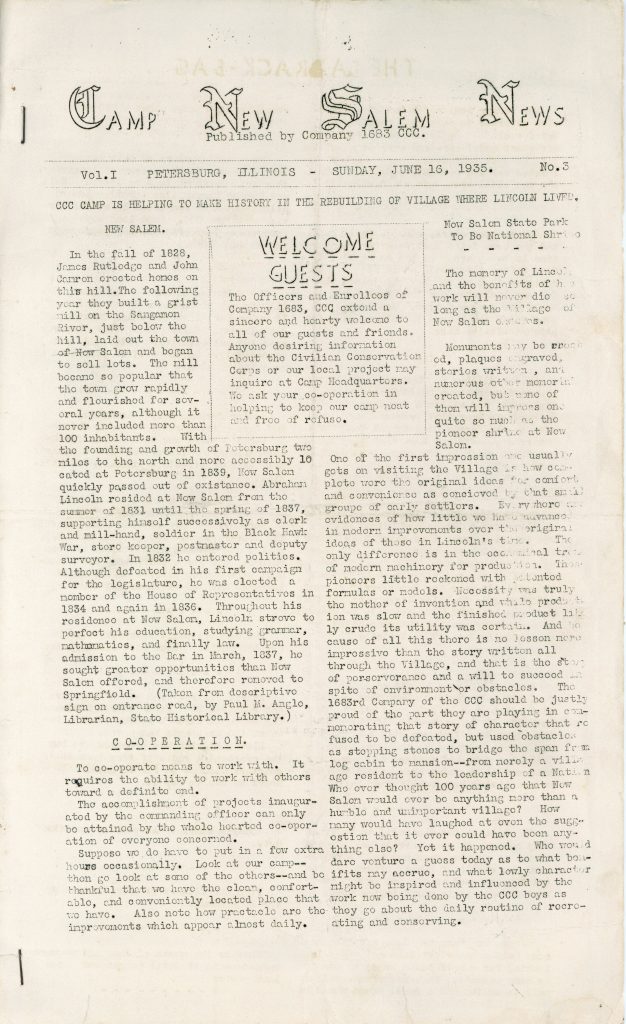

New Salem, the village where Lincoln learned law and won public office in the 1830s, was abandoned and converted to a cow pasture from 1840 until 1917, when it saw renewed public interest amid Illinois Centennial celebrations. Petersburg residents formed the Old Salem Lincoln League to erect replica cabins, produce a pageant on Lincoln’s life, and publish a popular book entitled Lincoln at New Salem.

In 1918, the League donated the land to the state to be incorporated as New Salem State Park. Extensive historical research and archaeological surveys allowed for an accurate reproduction of the 1830s village.

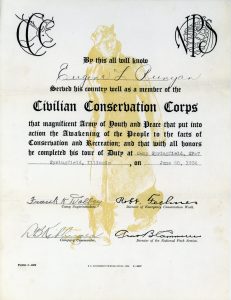

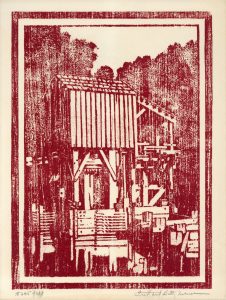

As the Great Depression dawned in the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps undertook this restoration work and constructed new park facilities.

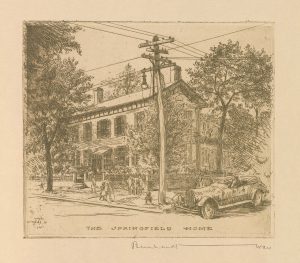

Unlike New Salem, the Greek Revival house that Lincoln called home from 1844 to 1861 at Eighth and Jackson Streets in Springfield never sat unoccupied. New occupants and a century of city development brought changes to the interior and exterior.

Following President Lincoln’s death, Mary Lincoln and her eldest son, Robert, co-owned the family home, renting it to a series of tenants, many of who opened the house to public visitation.

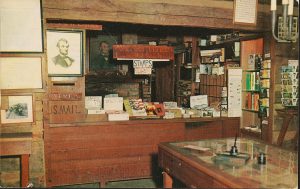

Mary passed away in 1882 and Robert Lincoln grew increasingly frustrated with the house’s renters–particularly O.H. Oldroyd, a tenant from 1883 to 1887, who frequently failed to pay rent despite turning the house into a profitable cabinet of Lincolnian curiosities where visitors paid to view thousands of artifacts from Oldroyd’s private collection.

In 1887, Robert Lincoln conveyed the home to the State of Illinois under the provision that it be “forever kept in good repair and free of access to the public.”

Case 2

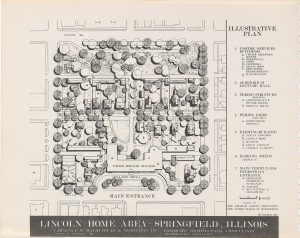

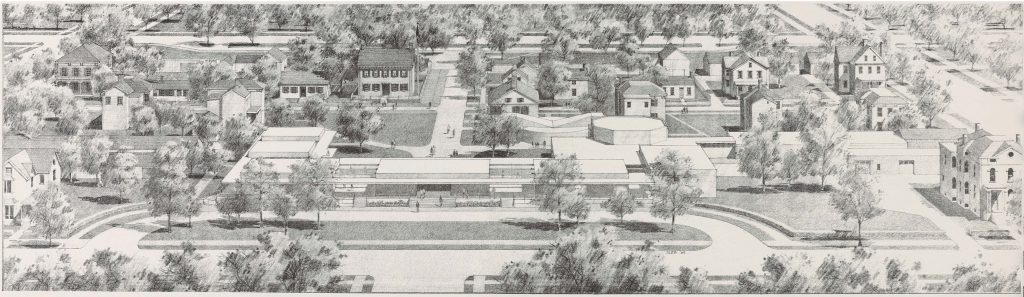

The state began managing the Lincoln Home as a public historic site in the late 1880s. The house’s continued popularity among tourists meant that the surrounding neighborhood evolved with paved sidewalks, power lines, streetcar rails, and gift shops replacing much of the historic setting.

The house changed with the neighborhood. By 1920 the state added an enclosed entryway for visitors. Electricity soon came to the house and in the 1950s window fans were installed.

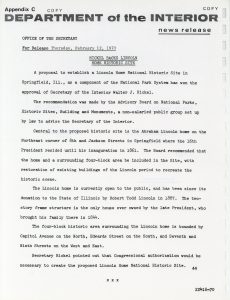

Not until the 1960s, near when the nation celebrated the Civil War Centennial, were proposals for reverting the home and neighborhood to an 1860 appearance seriously entertained. These culminated in a proposal for a new National Historic Site, which Congress approved in 1971.