The story of this Western Illinois village begins across the ocean in Sweden. There, in the early nineteenth century, a Landberga farmer and flour salesman named Erik Jansson claimed to have experienced two extraordinary events. The first came when Jansson – a sufferer of rheumatism for much of his life – was plowing a field in 1830 and collapsed. Lying on the ground, he began to pray and was miraculously cured. The second event occurred during a visit to the market where Jansson, in his own words, heard the voice of Christ instructing him to “take up my cross and preach my gospel to all who will listen.” And so he did. Earning a reputation as the “Wheat Flour Messiah,” Jansson’s beliefs strayed further and further from the Swedish state’s Lutheran Church as he began burning dissenting religious texts, preaching that true Christians were already without sin, proclaiming himself “the vicar of Christ on earth,” and asking his followers to help him build a “New Jerusalem.”

The roots of Bishop Hill itself can be traced to 1846 when Jansson and 1,200 of his followers immigrated to the United States to escape persecution in Sweden and to establish their utopian New Jerusalem. Settling in Illinois and naming their community after Jansson’s hometown of Biskopskulla, the so-called “Janssonists” set up their colony as a commune under the direct authority of Erik Jansson. Initially, the colonists had only cabins, tents, and dugout shelters to protect them from the elements. They lived off hardtack and corn porridge, toiled away day and night grinding corn, and worshipped at least four hours each day. Between these conditions and widespread disease, many colonists didn’t survive the first winter.

Nevertheless, the colony persisted as new waves of immigrants arrived. Over the next few years, permanent structures were erected. The Janssonists built cement, adobe, and occasionally wood homes. Learning how to raise cattle, grow crops, and make furniture, the colonists – under Jansson’s direction – soon turned Bishop Hill into a local center for wagons, furniture, and farm products. Proceeds from these sales went to expanding the colony by ten thousand acres on which they built a wood-frame church, brick dormitory, hotel, brewery, flour mill, blacksmith shop, a wagon store, a bakery, an apartment building, an administrative building, and more. Life meanwhile remained highly regimented with defined hours of work and worship. Jansson at various times even dictated whether colonists should remain celibate or marry to produce offspring (including arranging marriages himself).

Life at the Bishop Hill Colony began to change in 1850. The previous Fall, Erik Jansson had consented to a marriage between his cousin Charlotta Louisa “Lotta” Jansson and John Root, an outsider from New Orleans. When a new group of Swedish immigrants inadvertently introduced Asiatic cholera to the colony, Root wanted to leave Bishop Hill with his wife. Lotta, however, did not. What followed was a series of kidnappings in which Root and his friends attempted to take Lotta away from the colony against her will. When those efforts failed, Root filed suits against Erik Jansson in the Henry County Circuit Court. On May 13, 1850, when Jansson appeared in court to contest the charges, Root pulled out a pistol and fatally shot Jansson in the heart. John Root was subsequently convicted of manslaughter, but served just a year in prison. With Jansson gone, colony leadership was transferred to a board of seven trustees. Many colonists simply left, but those who stayed soon found Bishop Hill in financial ruins under incompetent and bickering leaders. Between 1858 and 1862, Bishop Hill Colony was slowly dissolved.

While the commune was dissolved, Bishop Hill became an incorporated town. Today, its 128 residents continue to celebrate the unique heritage of their quiet slice of “heaven on the prairie.” The village was named a National Historic Landmark in 1984 and became a tourist destination as an Illinois State Historic Site in 1946 with many of the original buildings like the church and administrative building still standing to this day. Every year, the community also puts on traditional Swedish festivals like Jordbruksdagarna, Lucia Nights, and Julotta.

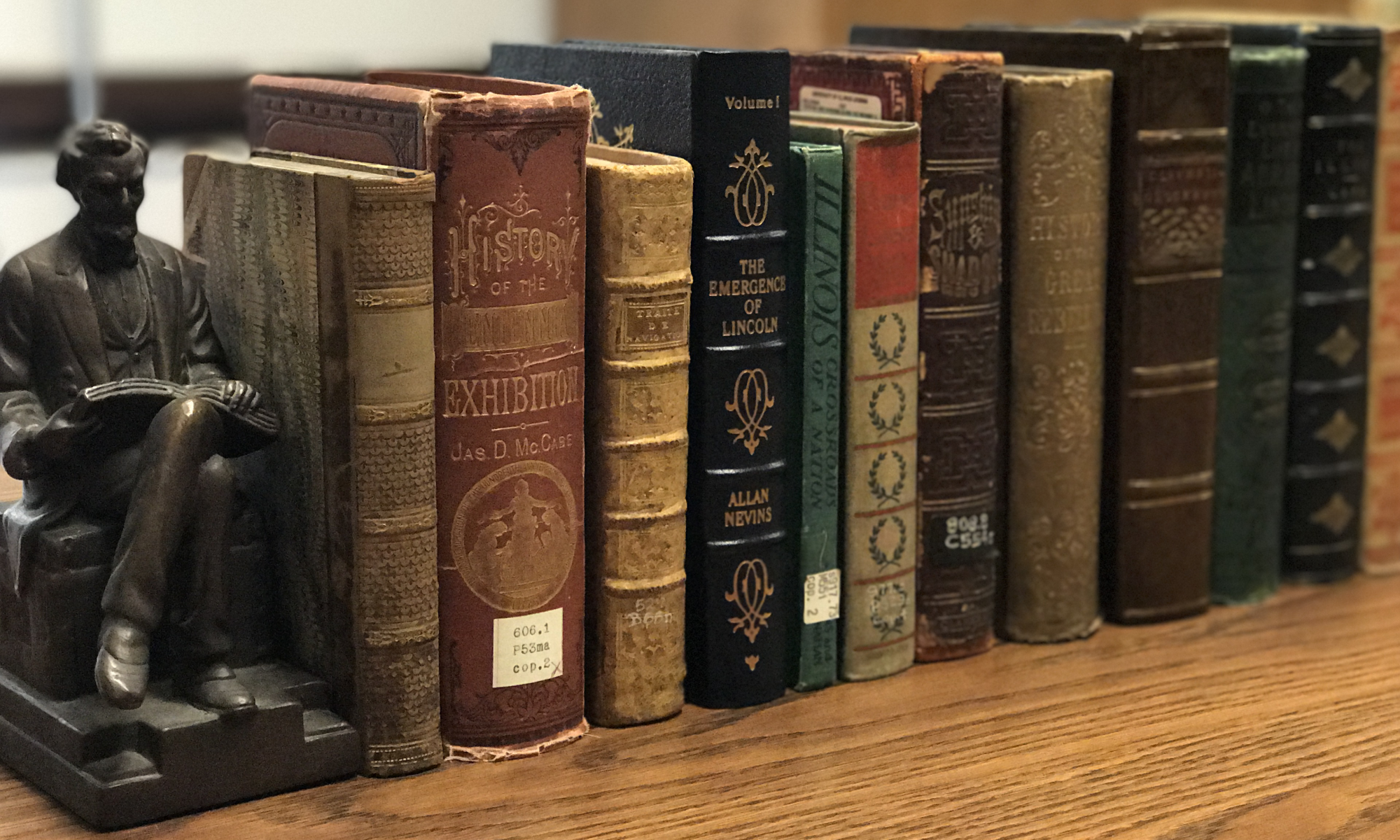

All this is just a taste of the fascinating history of this Henry County community. Want to learn more about Bishop Hill? Then stop by the Illinois History and Lincoln Collections or visit us online! From books like Bishop Hill: Fifteen Years that Last Forever to manuscripts like the Ethel W. Ijams Collection,circa 1745-1990 (MS 725) we have a variety of resources available for anyone interested in this small town.

IHLC Resources

Anderson, Theodore J., ed. 100 Years: A History of Bishop Hill, Illinois: Also Biographical Sketches of Many Early Swedish Pioneers in Illinois. Chicago: 1947. Call Number: 977.338 AN2O

Elmen, Paul. Wheat Flour Messiah: Eric Jansson of Bishop Hill. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1976. Call Number: B.J352 E.

Pratt, Harry E., ed. “The Murder of Eric Janson, Leader of Bishop Hill Colony.” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society 45, no. 1 (Spring 1952): 55-69. Call Number: 977.305 IL.

Soland, Randall J. Utopian Communities of Illinois: Heaven on the Prairie. Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2017. Call Number: 307.7709773 So41u.

Other Resources

“Bishop Hill.” Illinois Department of Natural Resources Historic Preservation Division. Accessed October 10, 2018. https://www2.illinois.gov/dnrhistoric/Experience/Sites/NorthWest/Pages/Bishop-Hill.aspx.

Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Bishop Hill Historic Site.” Encyclopaedia Britannica. Accessed October 10, 2018. https://www.britannica.com/place/Bishop-Hill-State-Historic-Site#ref274114.