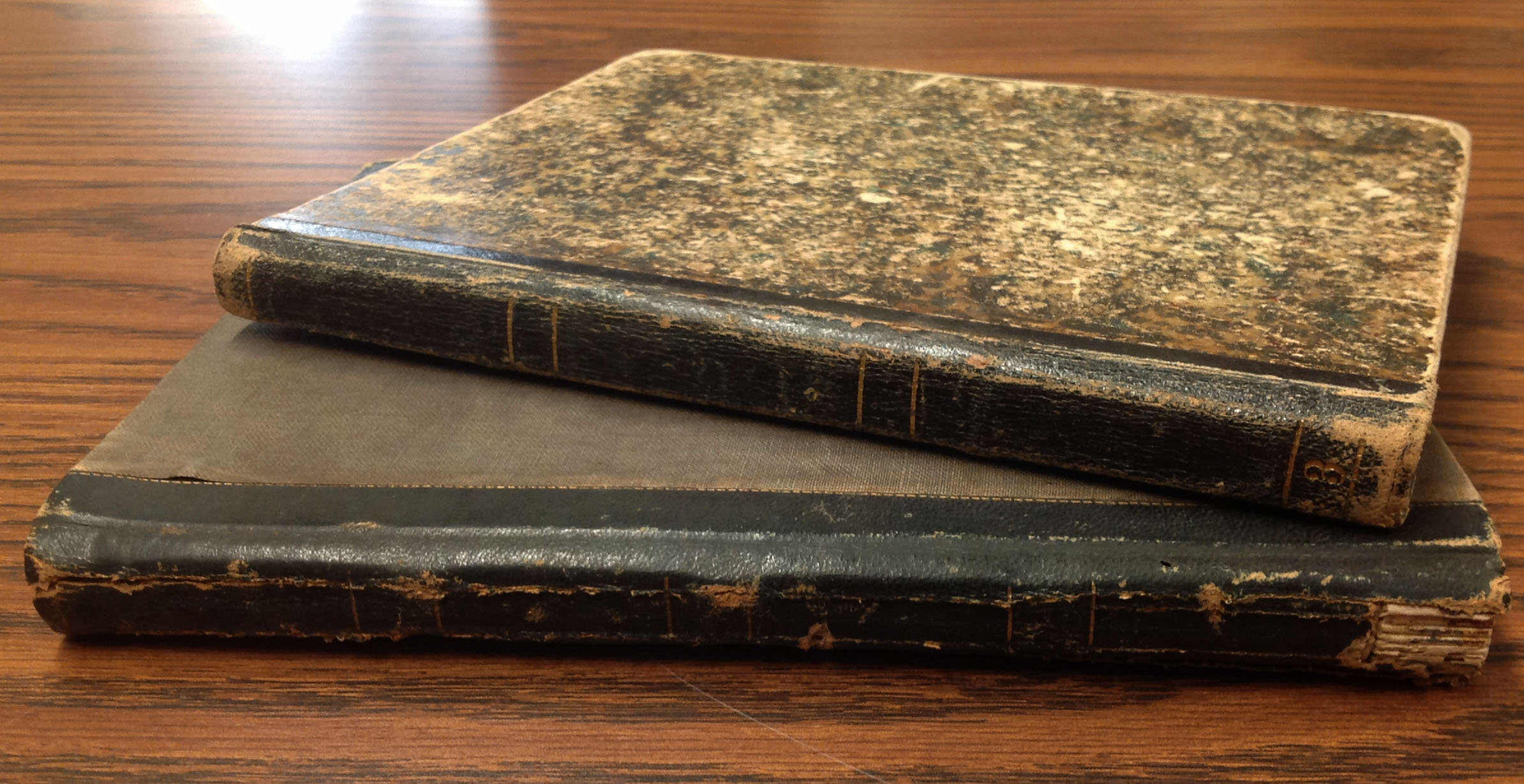

When a schoolgirl works through math problems and writes and sketches in her school notebook, little does she imagine it will someday adorn the shelves of a major research library. And yet, such was the fate of the school notebooks of Teresa Dalbey of Morgan County and Sarah E. A. Brown Leverett of Alton, Illinois, both of whom were young adolescents living and learning in Illinois in the 1850s. This month, as we celebrate education in Illinois in honor of the state’s bicentennial, Teresa’s and Sarah’s school notebooks allow us to gain insights into nineteenth-century schooling, as well as the thoughts, activities, and experiences of two young girls growing up in 1850s Illinois.

Girls’ Education in 1850s Illinois

Teresa’s and Sarah’s school notebooks contribute to the broader narrative of an evolving public education system and increasing educational opportunities for women and girls in the United States. Although we have little information about the Illinois schools Teresa and Sarah attended, we do know the decades leading up to their school experiences were marked by an increase in the quality and quantity of education to which girls and women had access. As scholar Nancy Green has noted, “The years between 1820 and 1850 saw the beginning of schooling beyond bare literacy, and continuance in school beyond the age of about twelve, for a large number of girls.”[i]

Education reformers of the mid-nineteenth century also drove the development of a nationwide public school system in the United States, shedding light on the importance of schooling and creating additional opportunities for all children to receive an education. As a result of a growing popular belief in the power of schooling to improve society, Illinois ratified a free school law in 1855 that enabled many children from a range of socioeconomic backgrounds across the state to learn together in the same classroom. ”[ii]

As a result of such reforms, public education was accessible to both Sarah Leverett, the daughter of a college professor in the growing city of Alton, and Teresa Dalbey, the daughter of a shoemaker in the small Illinois township of Arcadia Sarah Leverett’s town of Alton had opened five schoolhouses by 1856 and demonstrated a dedication to investing in those schools throughout the 1850s.[iii]

As a public school system evolved in the United States, the development of a more streamlined approach to curriculum and instruction was still underway. As Charles Beneulyn Johnson recalled of his schooldays in 1850s Illinois, schoolteachers were legally mandated to provide instruction in “reading, writing, arithmetic (the three R’s), spelling, history, geography, and grammar,” and might also teach “Latin, Algebra, chemistry and philosophy (physics),”[iv]

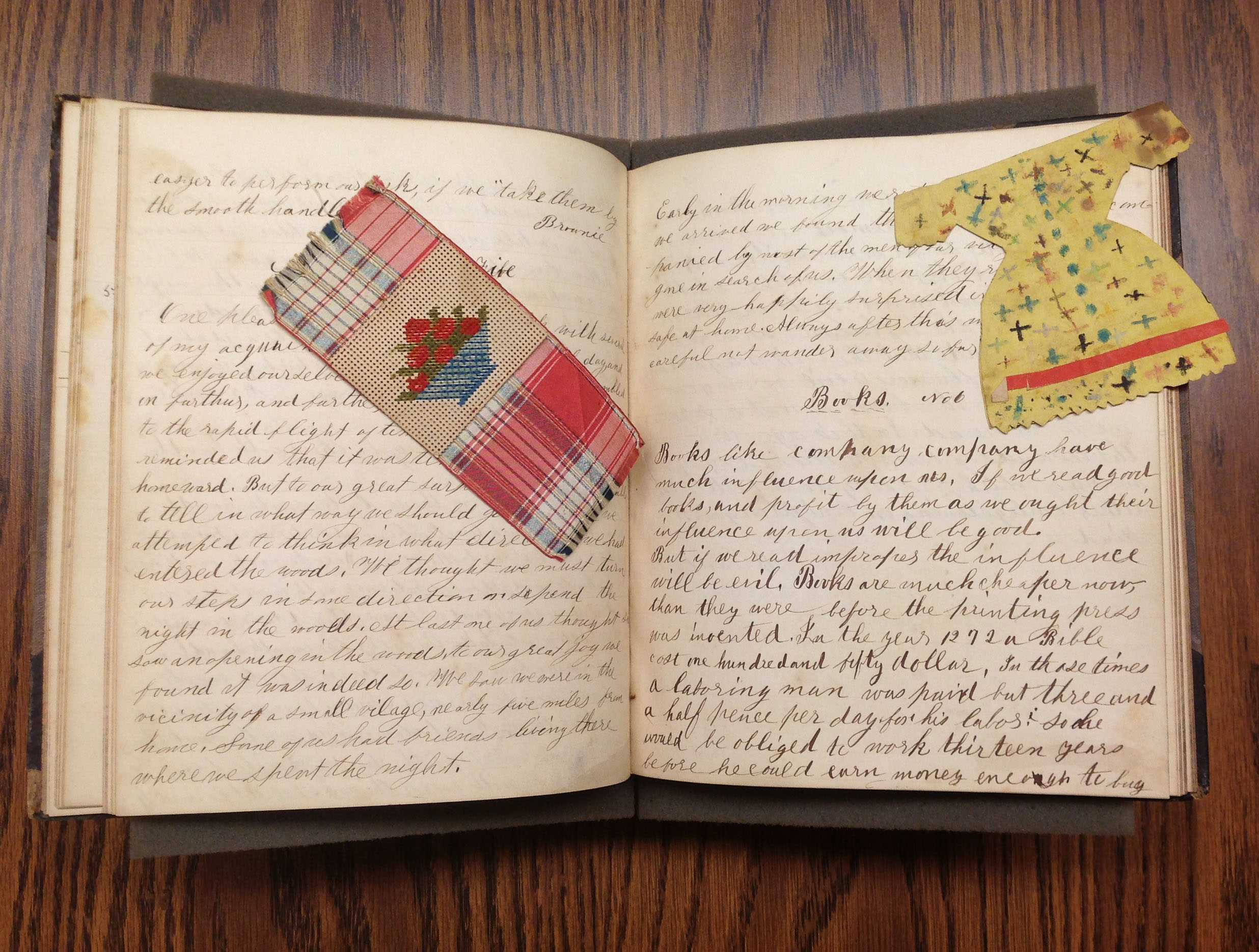

In addition to academics, students also learned a particular system of moral and social values “through the filtered lenses of textbooks.”[v] Even instruction in geography was designed to “contribute to religious principles as well as promote American nationalism.”[vi] The integration of moral, religious, and academic instruction in nineteenth-century American schooling is reflected in a composition entitled “Books” written by Sarah Leverett (signed with her nickname, Brownie L.”), in which she observes:

Books like company, company have much influence upon us. If we read good books, and profit by them as we ought their influence upon us will be good. But if we read improper the influence will be evil. Books are much cheaper now, than they were before the printing press was invented. In the year 1272 a Bible cost one hundred and fifty dollar. In those times a laboring man was paid but three and a half pence per day for his labor; so he would be obliged to work thirteen years before he could earn money enough to buy him a Bible this best of books.[vii]

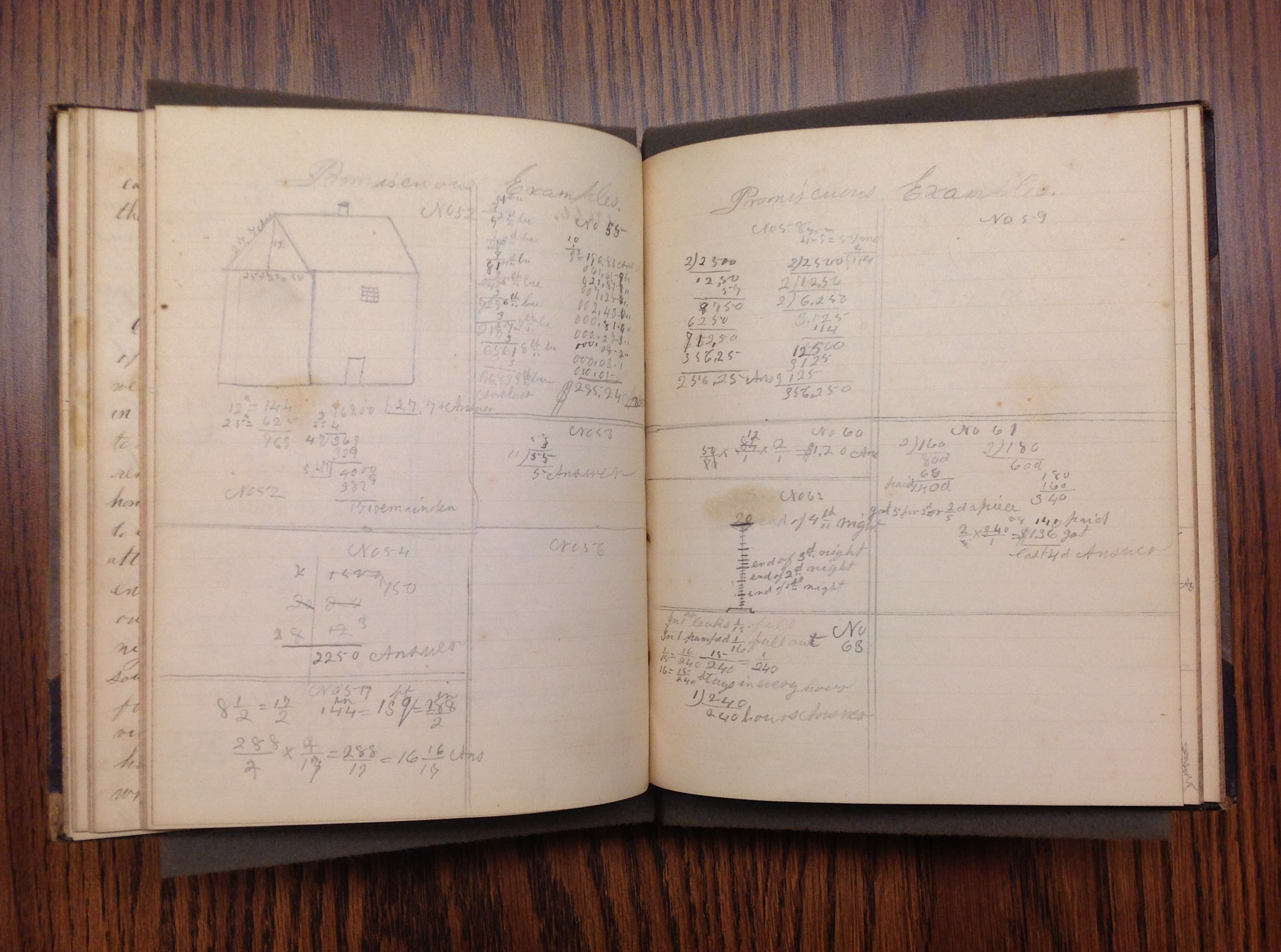

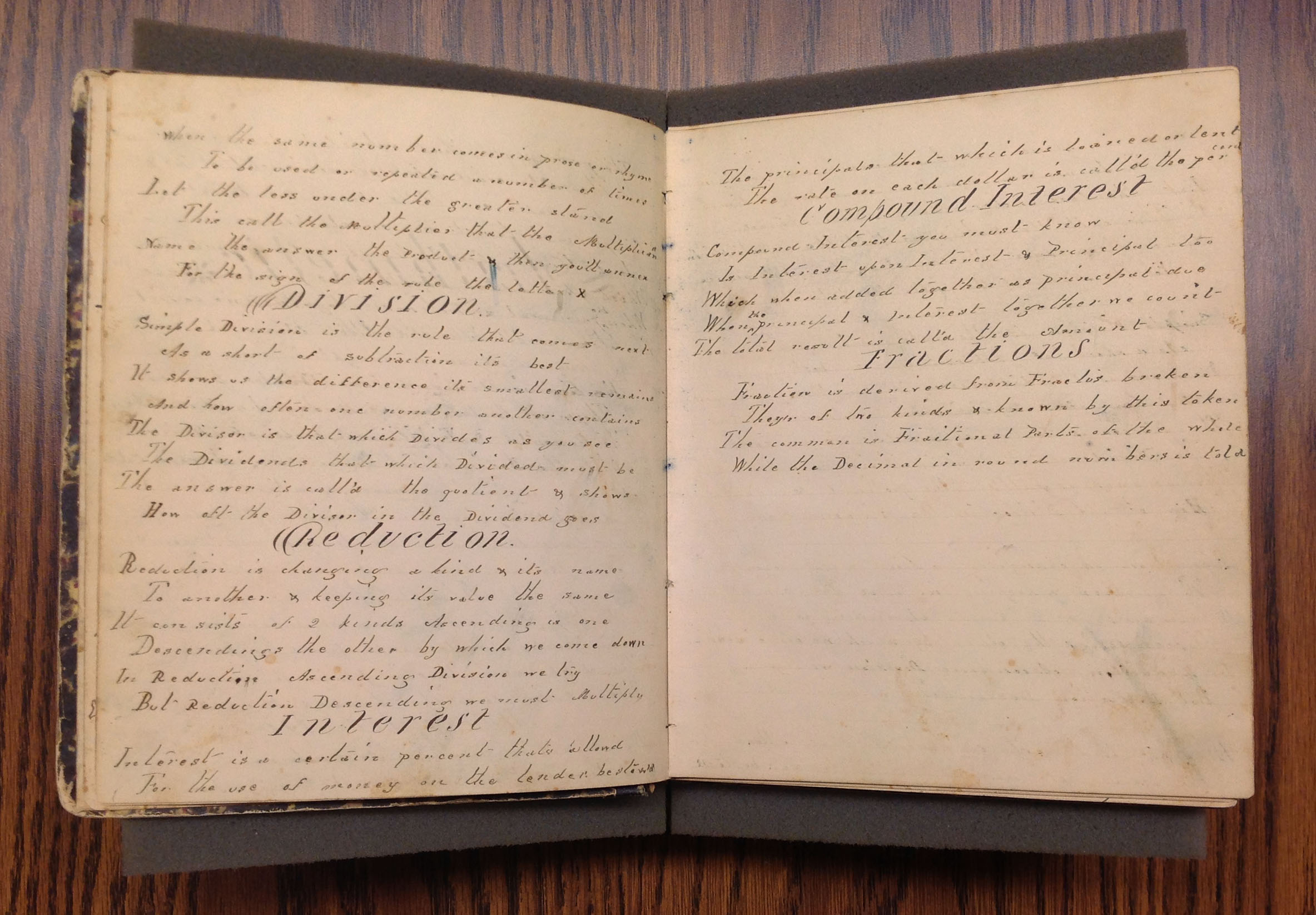

Because most students in the 1850s attended smaller rural schools without structured curriculum or even “consistency of teacher from term to term,” teachers often depended on textbooks, recitations, and “rhyme and rhythm” to bring “order and continuity to the educational experience.”[viii] In fact, it appears that Teresa Dalbey learned many of her lessons, including those in grammar, geography, and even mathematics, through the rhyme and cadence of pedagogical verse. For instance, a verse on compound interest in Teresa’s school notebook reads:

Compound Interest

Compound Interest you must know

Is Interest upon Interest & Principal too

Which when added together as principal due

When the principal & Interest together we count

The total result is call’d the Amount[ix]

The notebooks not only illustrate what educational practice was like in the 1850s, but also provide perspectives on the nature of childhood in this period.

Girlhood in 1850s Illinois

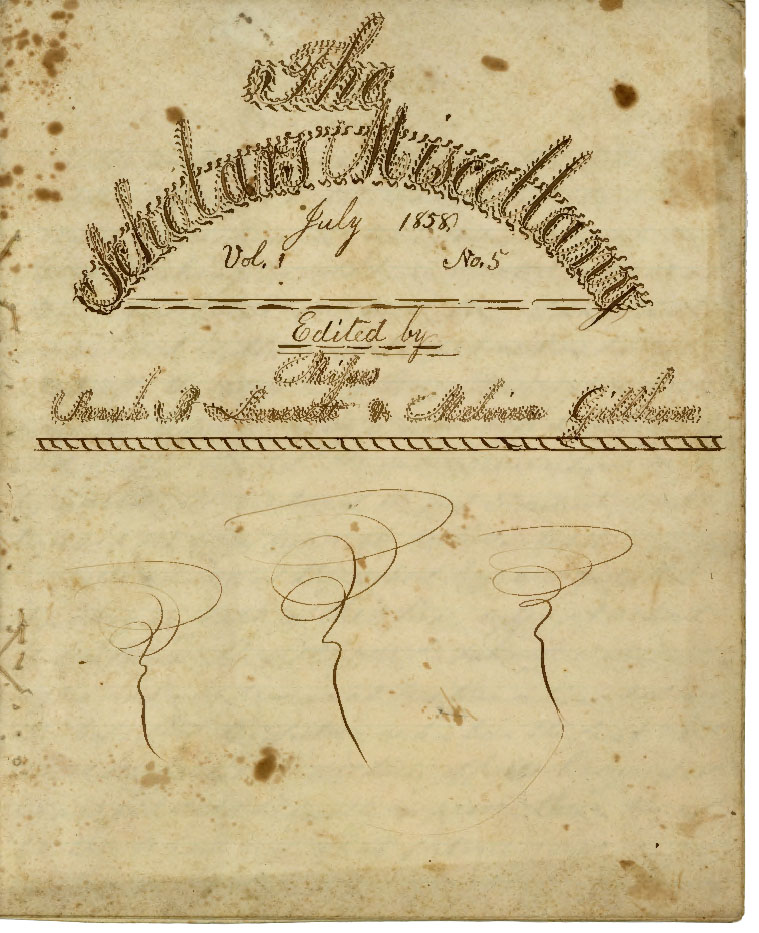

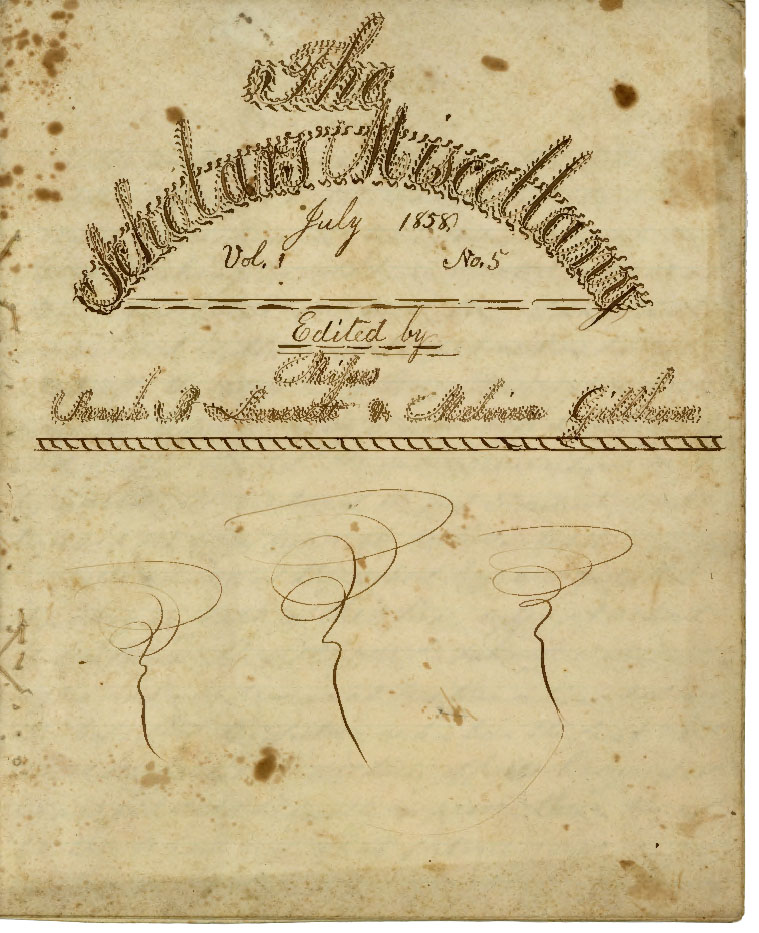

Sarah Leverett’s notebook includes many girlhood mementos that offer us glimpses of her pastimes and personality: drawings, poems clipped from a newspaper, bits of embroidery, dried leaves, handmade paper doll dresses, a portion of a play script, and a school publication entitled “The Scholar’s Miscellany,” July 1858, Vol. 1, No. 5, edited by Sarah and her friend Melvina Gillham. The items Sarah preserved suggest that she valued beauty, creativity, and friendship. We also learn that she was known to her friends as “Brownie,” a nickname derived from one of her middle names, Brown.

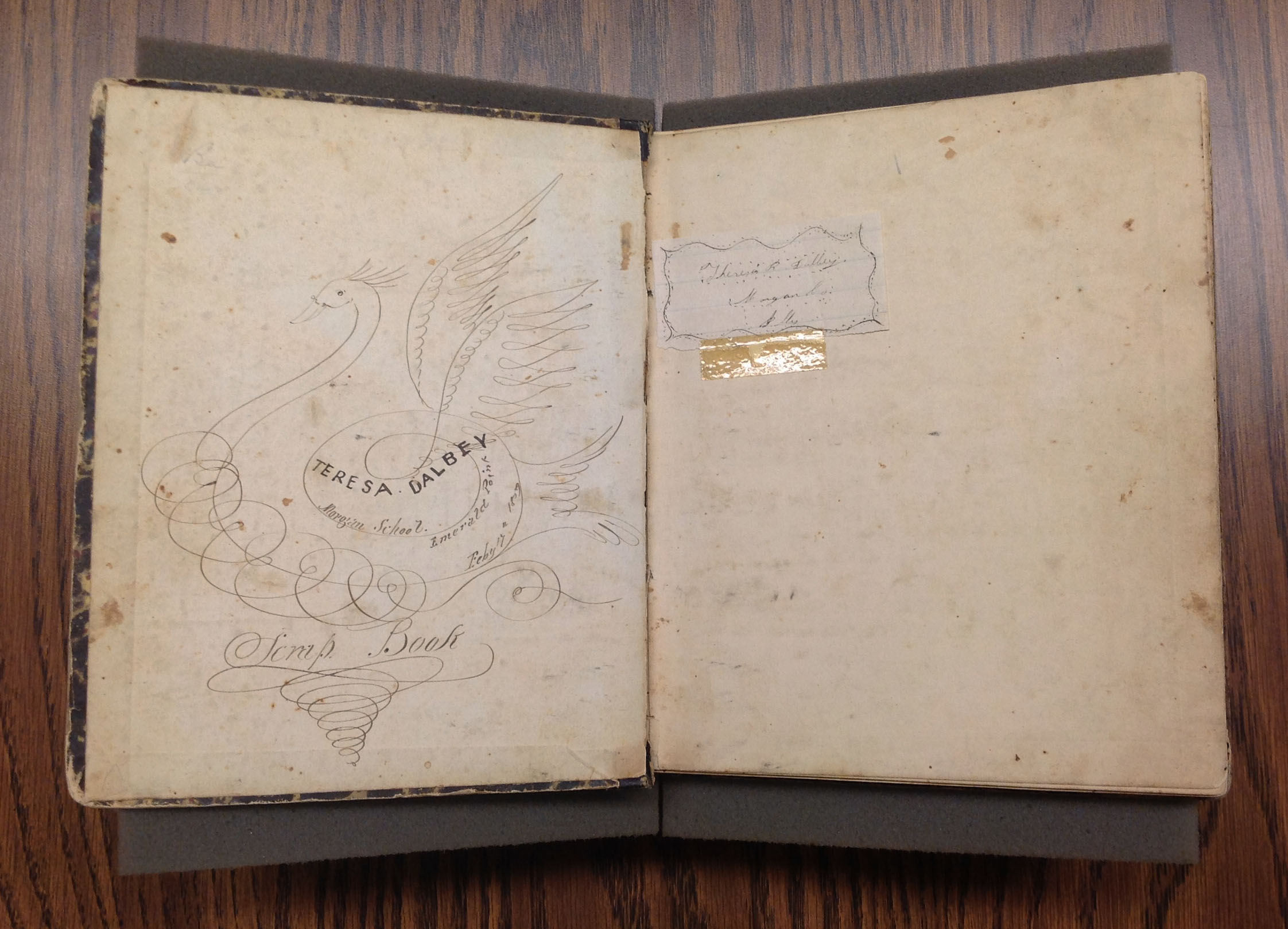

Like many schoolchildren nowadays, Teresa Dalbey appears to have passed some of her time in school doodling in her notebook. The inscription at the front of her notebook, for instance, is elegantly embellished with a pen-flourished swan. Subsequent pages include a few more drawings, as well as a variety of elegantly lettered subject headings.

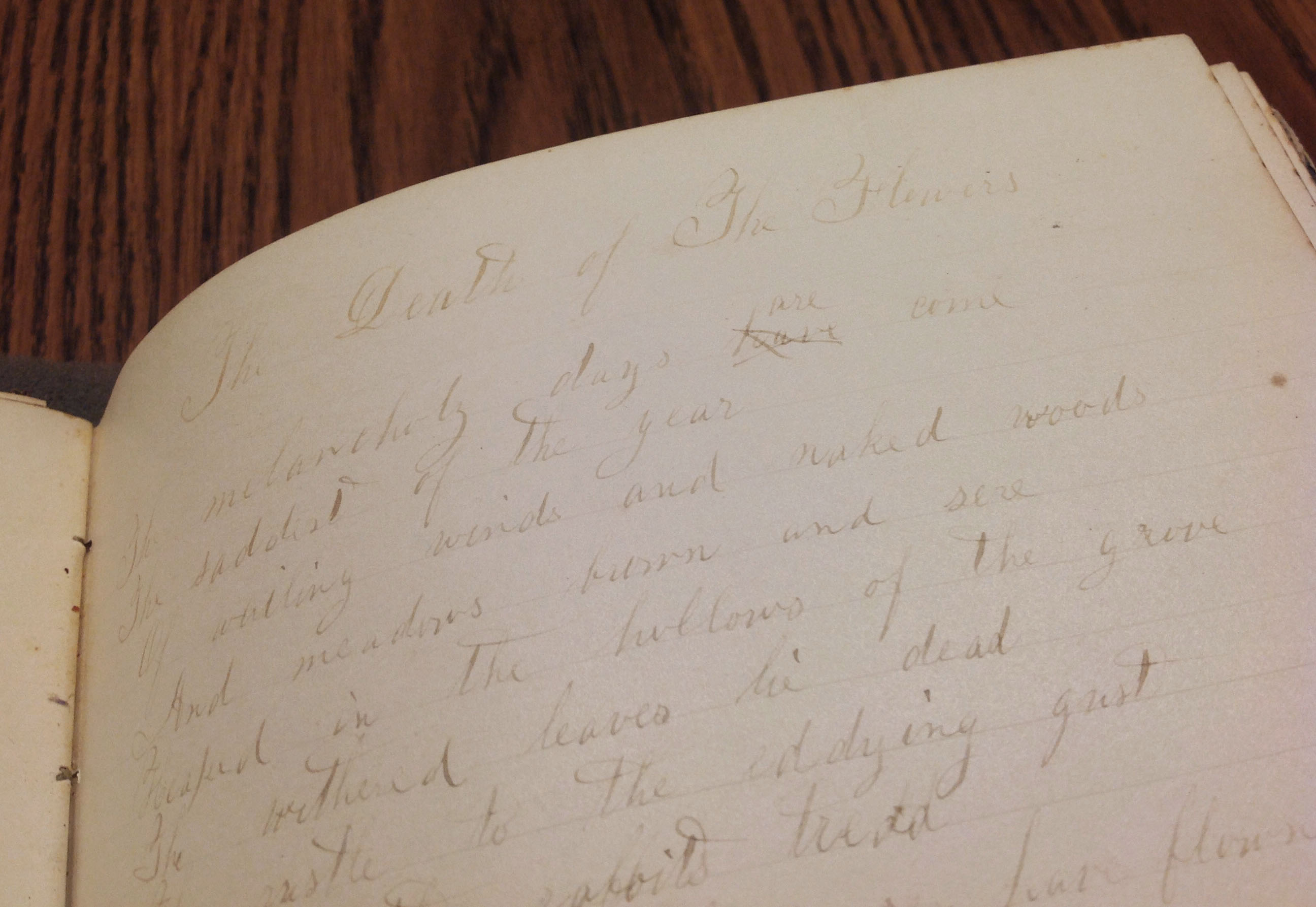

Teresa’s notebook contains few other traces of her interests and personality, but the many blank pages, as well as those written by another hand, represent the tragedy of her story. In 1864, five years after Teresa first wrote in her school notebook, her family set out from Illinois to Nebraska Territory. Due to the difficulties of the family’s 21-day journey, Teresa died just six weeks after their arrival. She was nineteen. Her family saved the school notebook book she had left behind. In the notebook, someone other than Teresa inscribed several poems. A stanza of one of the poems, “The Death of Flowers” by William Cullen Bryant, reads:

And then I think of one who in her youthful beauty died

The fair meek blossom that grew up

And faded by my side

[…]

Yet not unmeet it was that one

Like that young friend of ours

So gentle and so beautiful

Should perish with the flowers[x]

One exciting aspect of working with manuscript collections is the way in which items that appear mundane, like schoolgirls’ notebooks from the 1850s, in fact provide intimate insights into life in another era, adding depth and texture to our history. From the school notebooks of Teresa Dalbey and Sarah Leverett, we not only learn more about the history of public schooling in Illinois, but can also make inferences about what life was like for many girls growing up in the Midwest in the mid- to late-nineteenth century: sweet, simple, and sometimes too short. To peruse the school notebooks of Teresa Dalbey and Sarah Leverett or to learn more about the history of education in Illinois, we invite you to visit us and explore our print and manuscript materials here at the Illinois History and Lincoln Collections.

For more information on the history of public education in nineteenth-century Illinois, explore…

- More school notebooks in the Blair, Leverett, and Stifler Family Papers, 1805-2006

- Grace J. Alward Teacher’s Certificate, 1898

- Champaign County Illinois Schools, Papers, Records, 1877-93, 1921-41

- Droit School, Sugar Loaf Township, St Clair Co. School Records and Class Photographs, 1872-1925

- James Wellen Hays, Notebooks, Record Book, Photograph, 1865-1900

- Biennial Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction of the State of Illinois, 1859-1971

- Course of Study for the Common Schools of Illinois, 1897

- A Digest of the Laws of Illinois, Relating to Common Schools and School Lands, William Thomas, 1835

- The Illinois Teacher, 1855-1872

- The Black Struggle for Public Schooling in Nineteenth-Century Illinois by Robert L. McCaul, 2009

- …and more sources in our Manuscript Collections Database or the University of Illinois online catalog.

[i] Nancy Green, “Female Education and School Competition: 1820-1850,” History of Education Quarterly 18, no. 2 (1978): 130, https://www.jstor.org/stable/367796.

[ii] John Pulliam, “Changing Attitudes Toward Free Public Schools in Illinois, 1825-1860,” History of Education Quarterly 7, no. 2 (1967): 194-206, https://www.jstor.org/stable/367561.

[iii] Illinois Census, Morgan County, 1850 (Springfield: M.S. Hohimer, E.S. Gochanour, W.W. Allers, 1983), 240-241; James T. Hair, Gazetteer of Madison County (Alton: James T. Hair, 1866), 112-113.

[iv] Charles Beneulyn Johnson, Illinois in the Fifties (Champaign: Flanigan-Pearson Co., 1918), 103.

[v] Barbara Finkelstein, “Dollars and Dreams: Classrooms as Fictitious Message Systems, 1790-1930,” History of Education Quarterly 31, no. 4 (Winter 1991): 475, https://www.jstor.org/stable/368169.

[vi] Zachary A. Moore and Richard G. Boehm, “Factors Strengthening School Geography’s Curricular Position in the Nineteenth Century,” Social Studies 102, no. 1 (2011): 51, doi:10.1080/00377996.2010.484443.

[vii] Sarah E. A. Brown Leverett School Notebook, 1857-1858, Part 1, Box 32, Blair, Leverett, and Stifler Family Papers, 1805-2006, (MS 973), Illinois History and Lincoln Collections, page 68.

[viii] Catherine Robson, “The Memorized Poem in British and American Public Education,” in Heart Beats: Everyday Life and the Memorized Poem, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012): 51-53, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.cttq94zs.6.

[ix] Teresa Dalbey School Notebook, 1859-1864, Teresa Dalbey Composition Book and Family Biography, 1859-1864, (MS 968), Illinois History and Lincoln Collections, page 10.

[x] William Cullen Bryant, “The Death of the Flowers” (1825), quoted in Teresa Dalbey School Notebook, page 50.