Throughout the month of September, our focus is on education and educators in Illinois history. Follow along here and on our social media to learn more about the people and institutions that have shaped how Illinois learns.

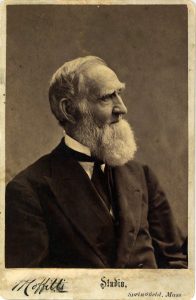

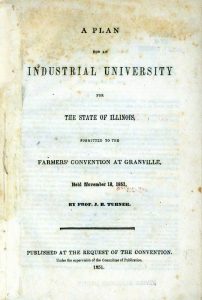

On November 18, 1851, Jonathan Baldwin Turner stood before a convention of farmers in Granville, Illinois and delivered an address that would play a part in changing the direction of American education. A 46-year-old minister, professor, and horticulturalist who had lived for twenty years in Jacksonville, Illinois, Turner believed that every state needed to institute industrial universities – universities dedicated to instruction in agricultural and industrial arts.

Turner saw the people of the United States as split into two “classes” – those of the “professional class,” who participated in medicine, law, religion, and other professions; and those of the “industrial class,” who were involved in agriculture, commerce, and physical labor. In his view, the industrial class was the most essential to society, but the needs of its members were not met by traditional universities. He had decided that the only way this could be addressed would be for the industrial class to have an institution of its own. Turner’s ideal was for this university to be state funded, and for control of it to be in the hands of the people.

Turner was not the only person to hold this view, but he was one of its most ardent supporters in Illinois. Born in Massachusetts in 1805, he had attended Yale, gaining a classical education before coming to Illinois in 1833. He served on the faculty at Illinois College in Jacksonville for close to 15 years, until his anti-slavery views and other issues led the administration to press for his resignation. After resigning, Turner devoted his attention to his horticultural work and the matter of education reform.

He joined other reformers nationwide in criticizing existing higher education, feeling that it was necessary to make universities accessible to the industrial class. He formed or joined several organizations, such as the Illinois Industrial League and the Illinois State Agricultural Society, to promote this cause to the Illinois General Assembly and the United States Congress. The plan that Turner shared at the Granville Convention was just one piece of a larger movement, but it spurred Illinoisans to action.

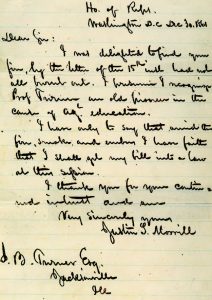

In 1852, Turner modified his plan to respond to a growing movement that proposed that industrial schools could be funded by land grants. Proponents of the idea suggested that public lands be donated to the states, so that the lands themselves or proceeds from their sales could be used to create the universities. Justin Morrill, a senator from Vermont, first presented a land grant bill to Congress in 1857. Despite some Congressional conflict over the bill and a veto by James Buchanan in 1859, Morrill had many supporters who lobbied for the bill’s passage, including Turner. After another passage through Congress, the bill became law in 1862, and plans were finally underway to make industrial universities a reality.

In 1863, Illinois accepted the provisions of what has been informally known as the Land-Grant College Act, or Morrill Act, and began preparations for establishing Illinois Industrial University. Jonathan Turner was disappointed, however, by the controversial dealings concerning the university’s location in Urbana and the choice of its first regent, John Milton Gregory. Turner distanced himself from the university for several years following its formal establishment in 1867. Nevertheless, he eventually made his peace with the university, and in 1872, he was present to lay the cornerstone for a new main building. Illinois Industrial University was renamed the University of Illinois in 1885, another choice that Turner criticized but eventually came to accept.

Turner was posthumously honored in various ways for his part in this industrial university movement, as well as for his other works. One such honor was that his name was given to the Plant Sciences Building at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, now known as Jonathan Baldwin Turner Hall.

You can learn more about Jonathan Baldwin Turner in the IHLC’s Jonathan Baldwin Turner Papers, 1823-1924 (MS 333), as well as the papers of his daughter, the Mary Turner and Henry Frost Carriel Papers, 1853-1927 (MS 509).

To learn more about the history of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, we recommend visiting the Mapping History site created by the University Archives, as well as examining their other resources for the university sesquicentennial.

I am a direct line descendant of Jonathan Baldwin, Turner. Currently I am working for his bio on Wikipedia which is almost finished. I mentioned this work on March 12, 2024. I am adding photos now. A lot of my sources came from the life of Jonathan Baldwin, Turner, by Mary Carriel which was mentioned above. Original edition printed in 1911 and the centennial edition, 1961. The Wikipedia article should be done by April 15, 2024 if not earlier. I would love to hear any stories about your connection to Jonathan Baldwin Turner male or female or related to him! Ralph Turner…..have you done your DNA and family tree? Best to all! Please check out Wikipedia’s bio on JBT soon!

William Gerald Turner and William Turner

Loved to hearing about your relationship to JBT. I have the same relationship through Mary Carriel Turner. JBT is my second great grandfather. Currently, I have been working on a bio for him on Wikipedia. You might want to take a look. Let me know what pictures you’d like to see go in there! The earlier bio just didn’t describe this great man in any depth so I have worked on it for many hours……ideas are appreciated!

I would love to talk further about my 3rd great grandfather, J. B. Turner. My great grandmother, Annie Paullin was J.B.’s granddaughter. Additionally, my great grandfather, Asa Turner was the nephew of J.B. Turner. Asa Turner was a son of Avery Turner, who was J.B.’s brother. After moving west from Templeton, MA, J.B. and his three brothers made there homes at first around Quincy, IL. The four brothers were Asa, Avery, Jonathan and Edward. My great grandfather, Asa, made his home in Hannibal, MO and had coal mining interests in Arkansas. Asa’s son, Edward Louis Turner, was my grandfather.

I am a descendant of J.B. Turner via my grandmother, Anna Myra Turner. I would be happy to correspond with anyone interested in this Turner line, including the female extensions.

In response to William, my name is Ralph Turner. I can trace my ancestry to Baldwinville (very near to Templeton) MA. I have made a cursory attempt, but have not been able to make a direct connection to JB. I am very active in supporting our local (UMAINE) Cooperative Extension service, and so I have a special interest in JB’s contribution to the Land Grant system. As a current farmer and a degreed mechanical engineer, I’m inclined to conclude that there must be a genetic component to the question of how I got to where I am. I would be happy to share what I have in the hopes of making this connection.

Thank you for the article. I am a direct descendant of J.B. Turner. I am writing a family history that concentrates upon the our family history in Illinois, Missouri, Massachusetts, Iowa and Arkansas. I would appreciate any information that is accessible. I hope to visit the IHLC soon.