For the month of May, we’re celebrating Illinois innovations in honor of the bicentennial. From cellphones to MRIs to black holes to carbon dating, Illinois has a long history of ingenuity. Follow along on our social media for weekly snapshots of #IllinoisInnovation.

In early 1905, an instructor teaching European history at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign was called on for a new task by University President Edmund James. The Renaissance historian was to make his way to Randolph and St. Clair Counties in search of a reported stash of unpublished colonial French documents. In those local archives, Clarence Walworth Alvord found not only those French sources – which themselves provided “significant windows into the earliest colonial history of the Midwest” – but a host of other documents on pre-statehood Illinois history called the Cahokia Manuscripts, Kaskaskia Manuscripts, and the Menard Papers. These finds altered the course of not only Alvord’s career but of the historical profession. Laying out a plan for the “exhaustive publication of the material for the history of Illinois,” the Europeanist had begun a new path as an Americanist – one who would help invent a new, professionalized local and regional way of studying the past.

It was hardly a given that Alvord would wind up studying the Prairie State’s history. Coming from a long line of New Englanders, he was born in Massachusetts in 1868 and had attended Williams College before going on to Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin, Germany to study “scientific” history. It was the pursuit of a PhD at the University of Chicago which brought Alvord to Illinois, but he soon dropped that program to teach history and mathematics at Urbana’s University Laboratory High School. Eventually, he was made an instructor in the Department of History at the university, but it was his archival finds in 1905 that spurred him to write a dissertation on Virginia’s former County of Illinois and thus earn his PhD – and the rank of assistant professor – here.

At the time Alvord was entering Midwestern history though, the history profession was, in the words of Wisconsin historian Curtis Nettels, “almost a monopoly of the Atlantic seaboard.” Recognizing this, in 1907 a group of scholars split from the Eastern-dominated American Historical Association to form the Mississippi Valley Historical Association (MVHA). Alvord, who very much agreed that the “development of the Northeast, particularly of New England, [had] usurped too prominent a place in the annals of America,” served as the new organization’s first full-term President.

Finding that the state and regional histories of the Midwest were integral parts in the national narrative, Alvord used his position to promote and produce “real history” which went beyond the great men of political history to showcase “far greater knowledge of the life of the people.” In 1913, he founded and edited the MVHA’s new scholarly journal: the Mississippi Valley Historical Review (MVHR). In the MVHR, Alvord looked to publish scholarship that was “clear,” “self-explanatory,” and which served the “great public” as the “organ of the Westerners.” Beyond that, Alvord was named editor of the ambitious Illinois Historical Collections, publishing the rich materials like the Cahokia Manuscripts he uncovered in 1905, and co-author and editor of the Centennial History of Illinois series.

Much of this work was done at the Illinois Historical Survey (IHS), headed by Alvord. In this “veritable laboratory of state history” on the fourth floor of Lincoln Hall at the University of Illinois, Alvord and his colleagues used collaborative methods to create, in the words of Illinois historian Robert Morrissey, “an entirely new historical infrastructure for telling the history of the early West.” From establishing a major archive for local and regional history, publishing that archive in the Illinois Historical Collections, and editing the MVHR to writing and editing the Centennial History and other landmark works on Illinois and Midwestern history, Alvord and his IHS associates “cleared the ground” for the development and writing of the long-ignored and yet absolutely vital history of the trans-Appalachian West.

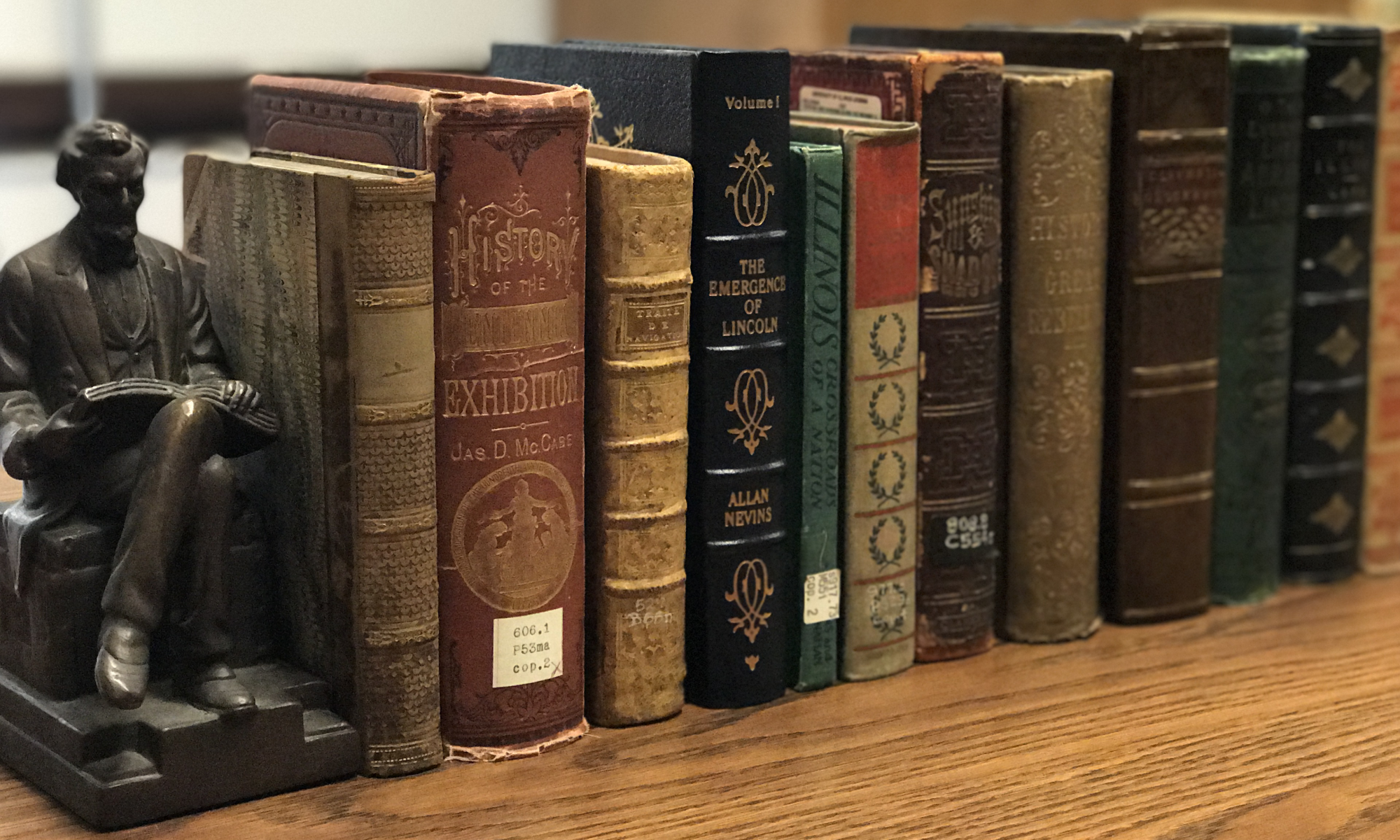

The legacy of Clarence Alvord and his generation of social “Prairie Historians” is very much alive today. The Mississippi Valley Historical Association has become the gargantuan Organization of American Historians (OAH). Alvord’s Mississippi Valley Historical Review is still the journal of record on US history as the OAH’s Journal of American History. And the innovative local history lab that was the Illinois Historical Survey lives on as the Illinois History and Lincoln Collections here at the University of Illinois.

Sources

Buck, Solon J. “Clarence Walworth Alvord, Historian.” Mississippi Valley Historical Review 15, 3 (December 1, 1928): 309–20.

Lauck, Jon K. “The Prairie Historians and the Foundations of Midwestern History.” Annals of Iowa 71, no. 2 (2012): 137–73.

Morrissey, Robert Michael. “Clarence W. Alvord: The Illinois Historical Survey and the Invention of Local History.” In The University of Illinois: Engine of Innovation, edited by Frederick E. Hoxie, 103-109. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2017.